.jpg.700x700_q85_autocrop_replace_alpha-%23FFFFFF.jpg)

#MB64

Ca. 1898-1899

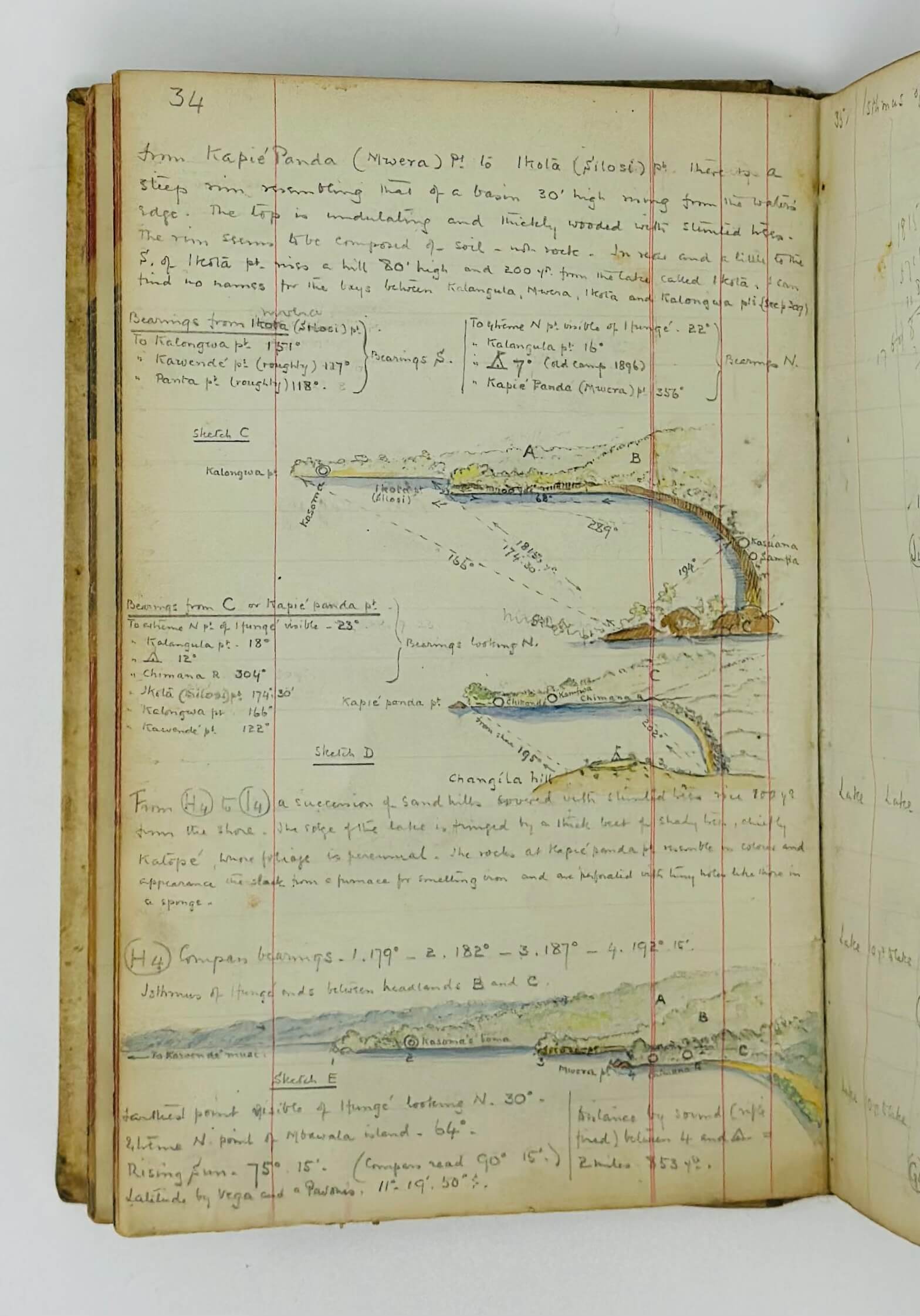

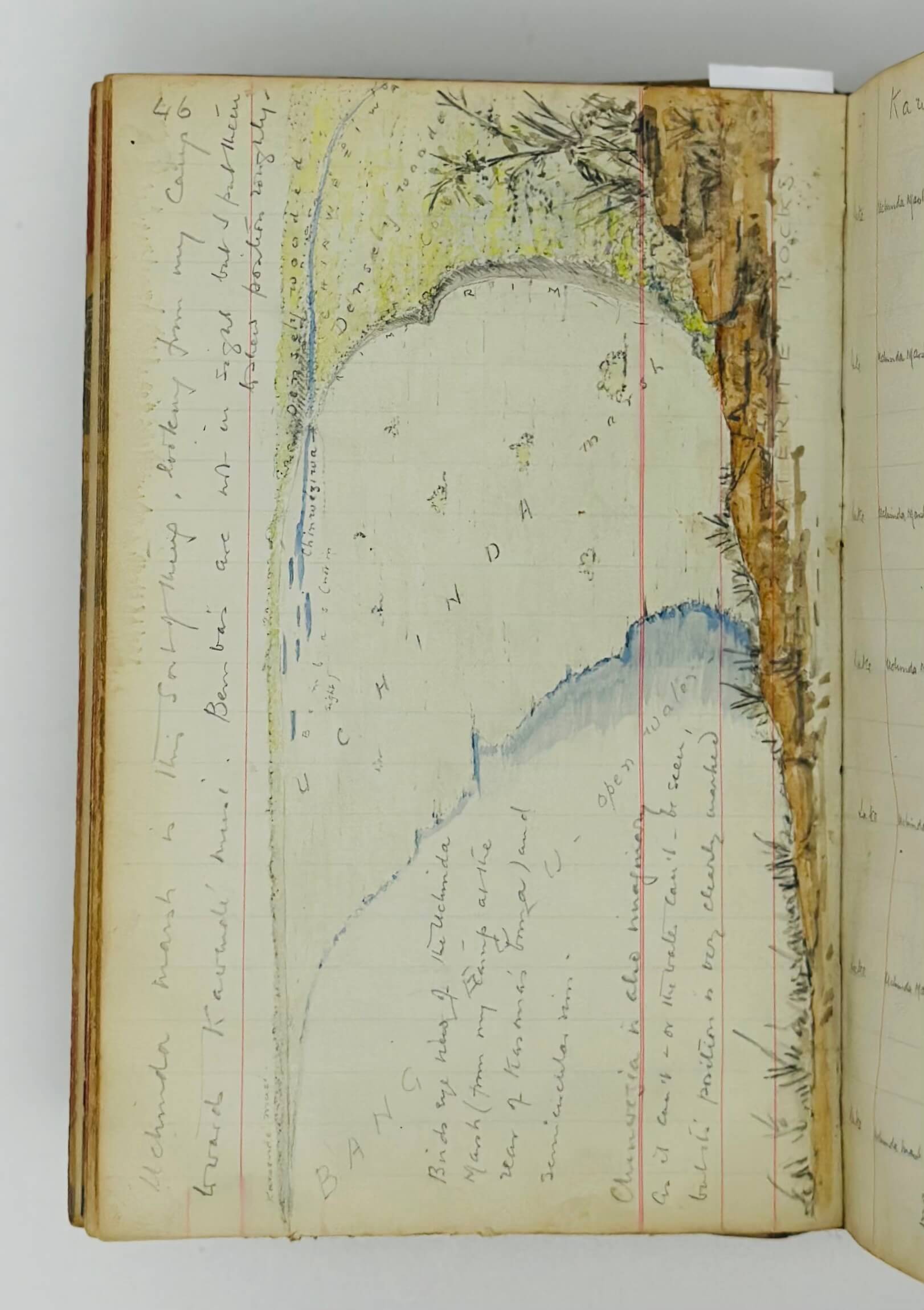

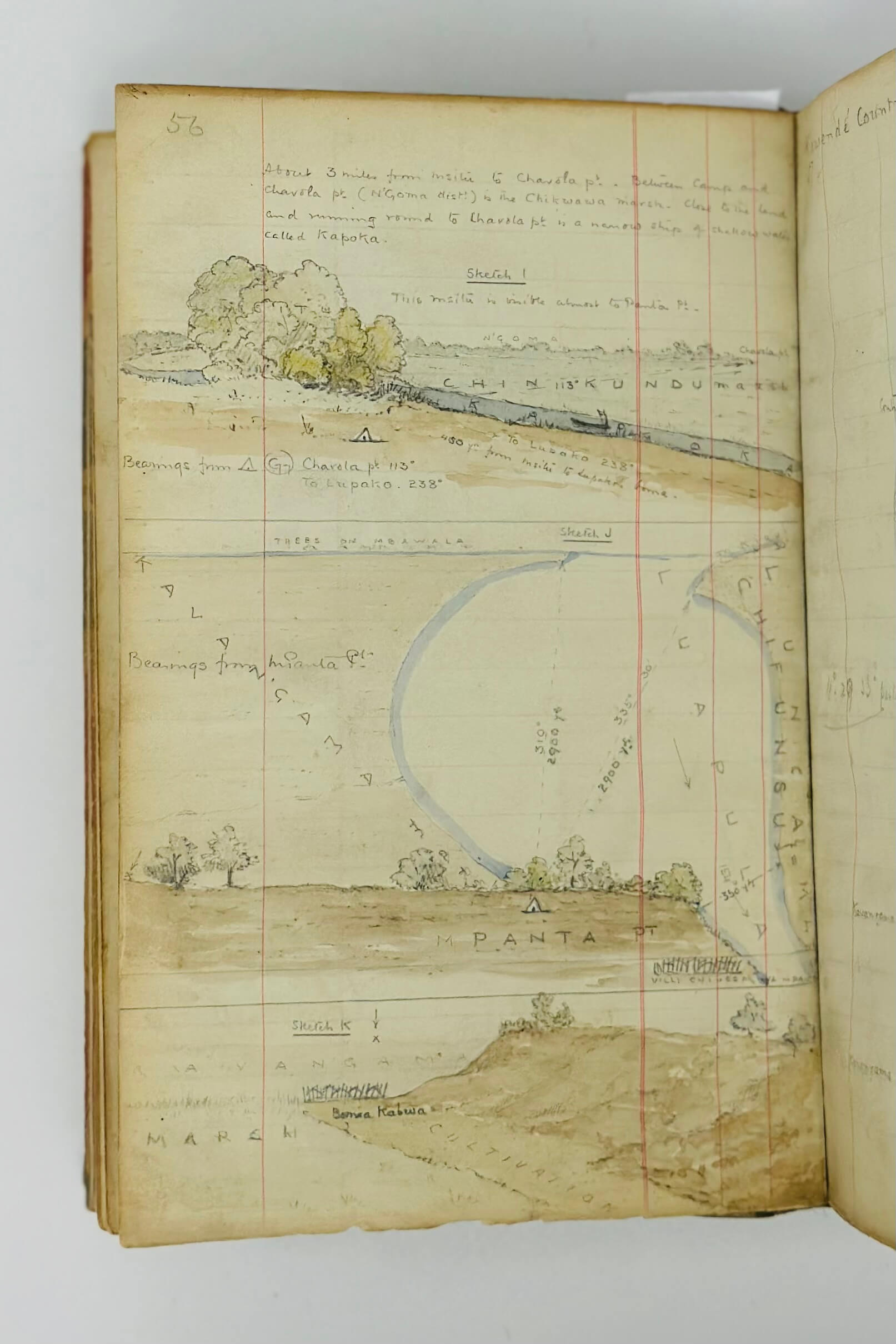

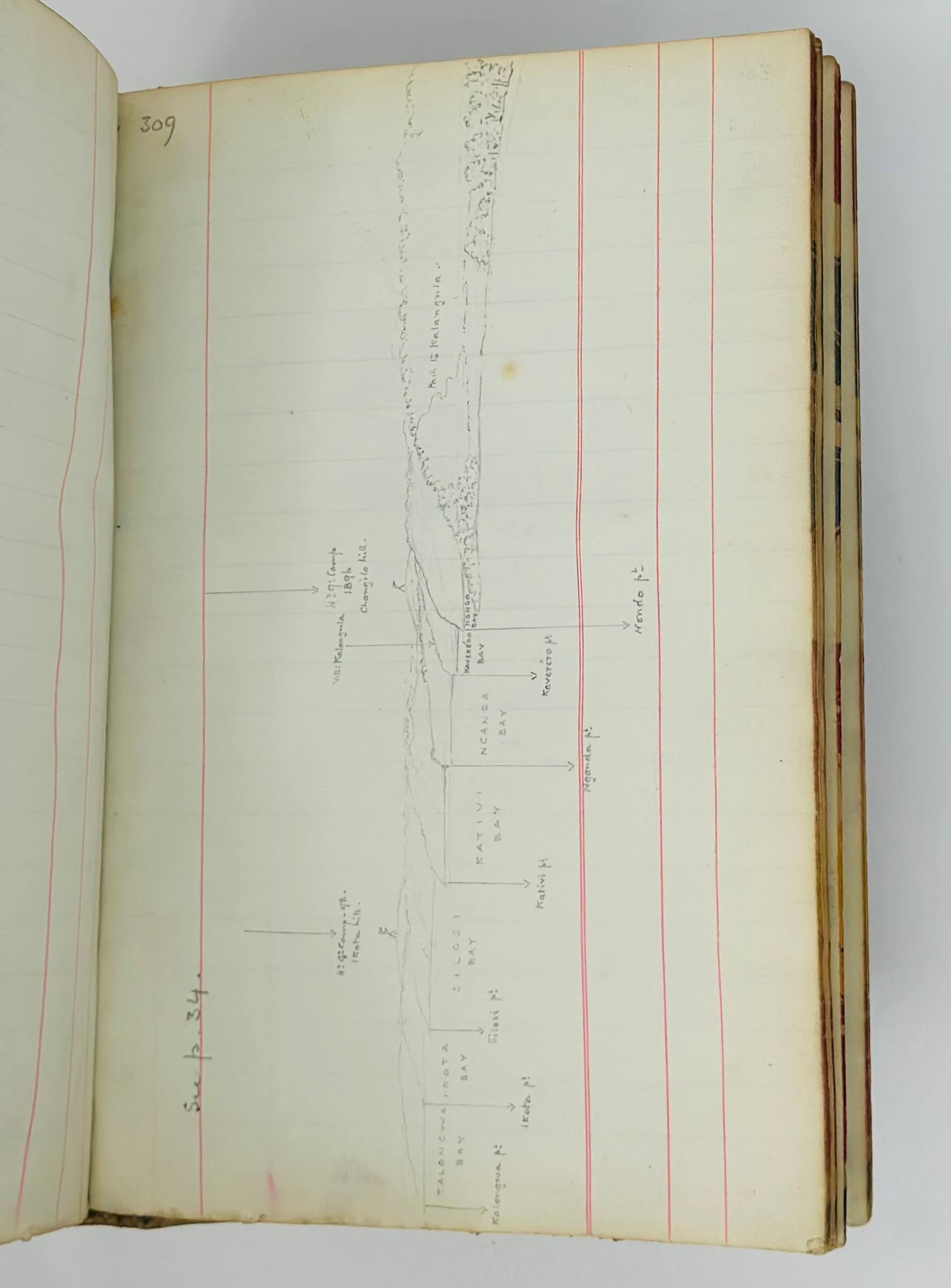

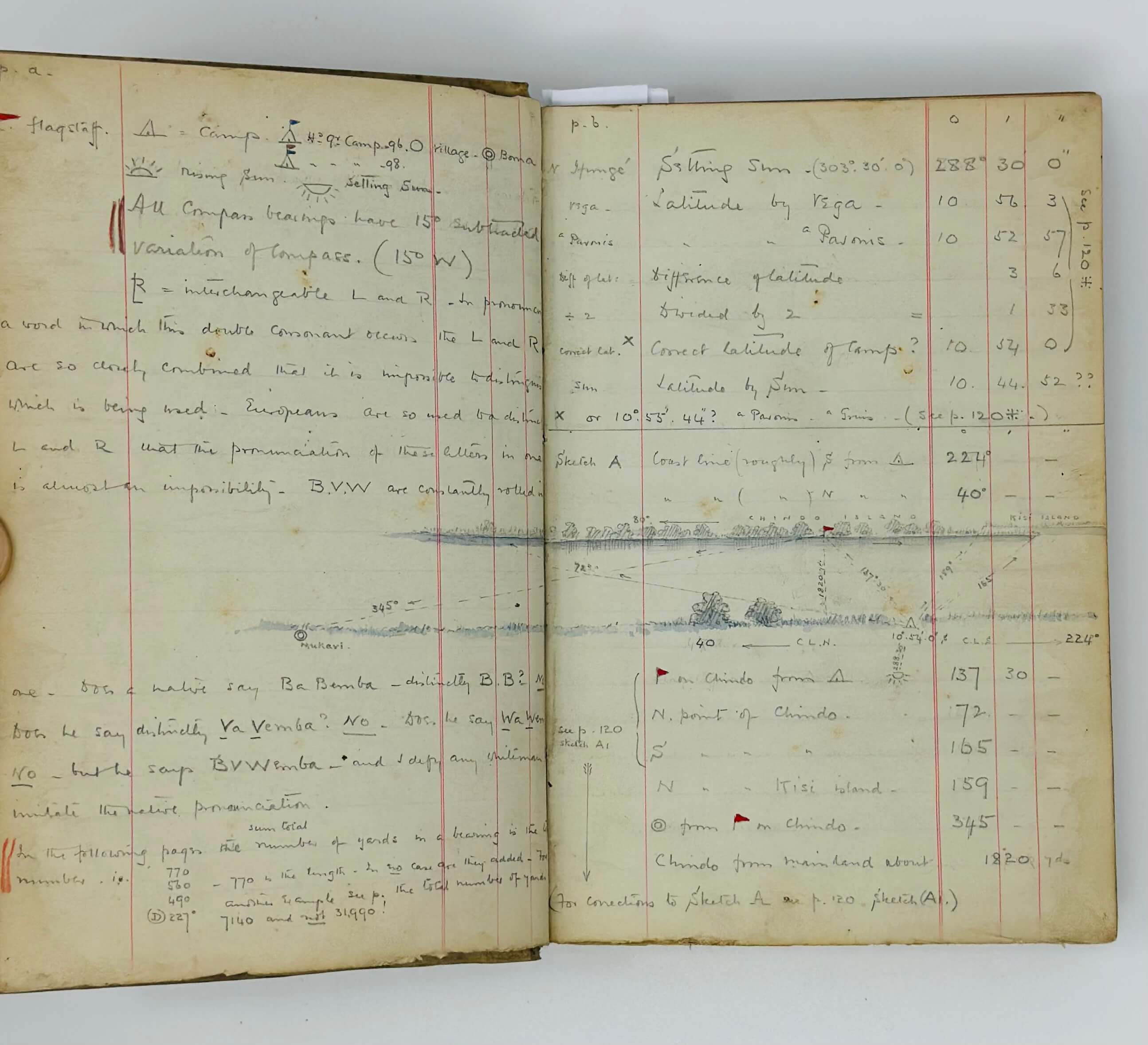

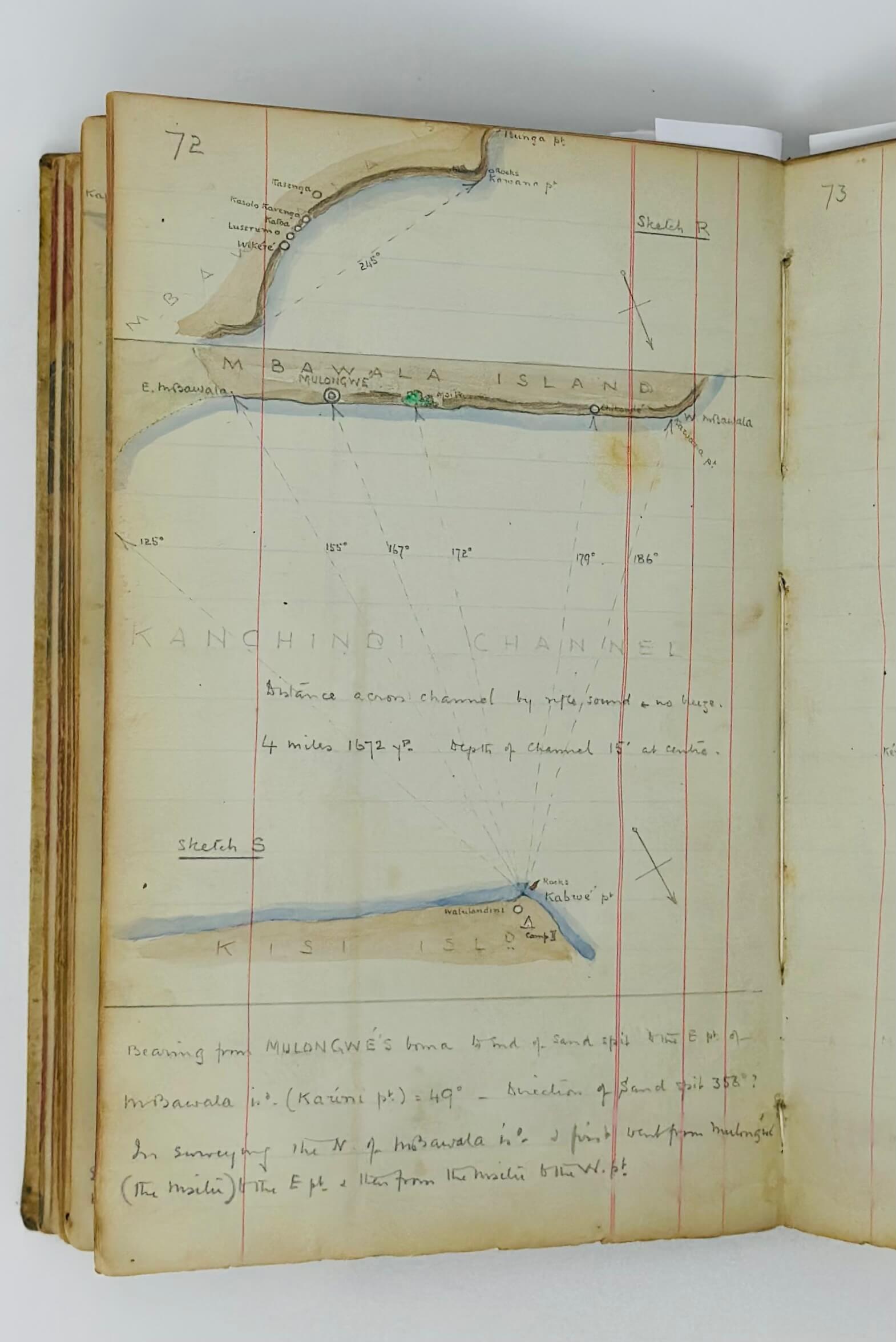

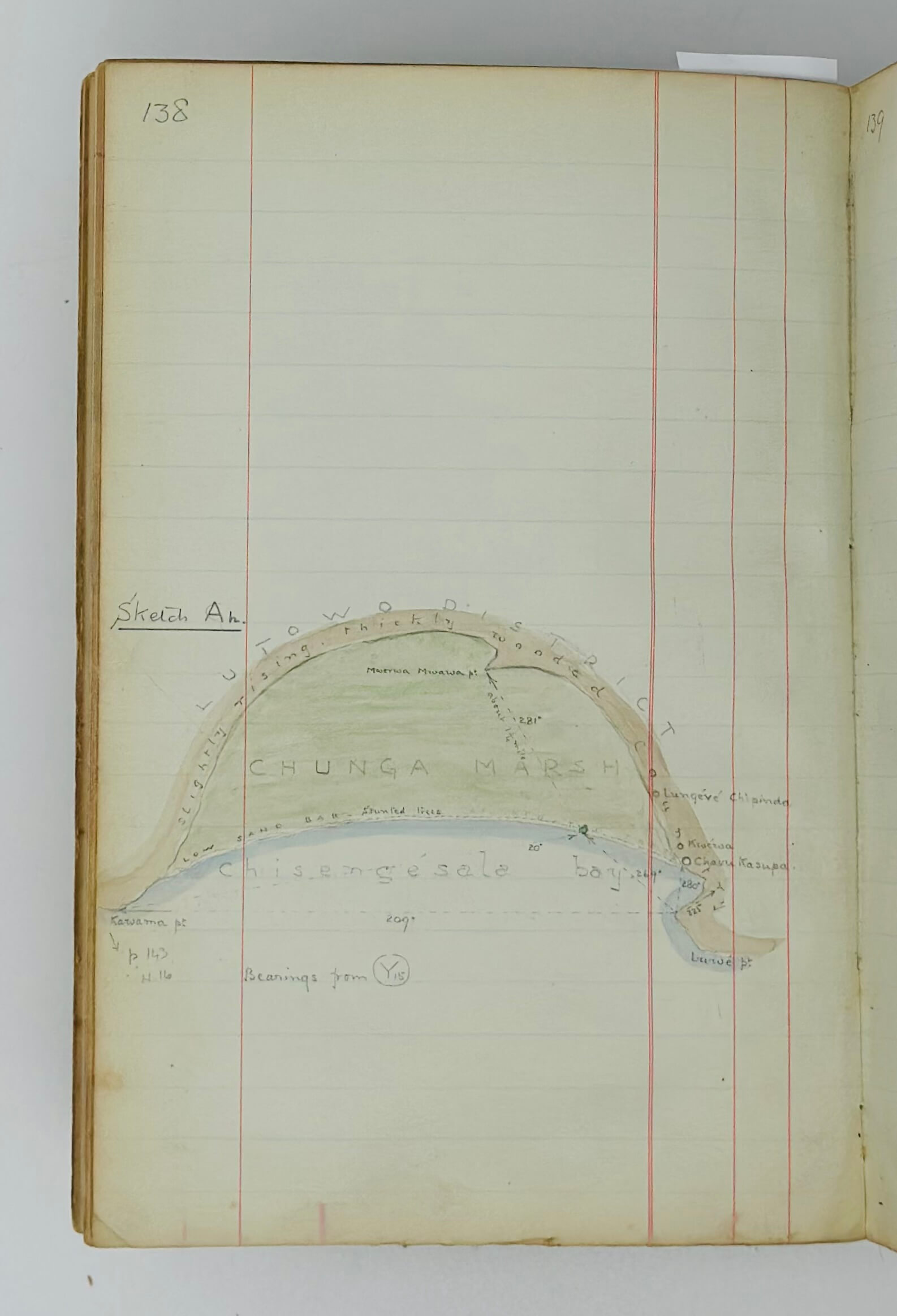

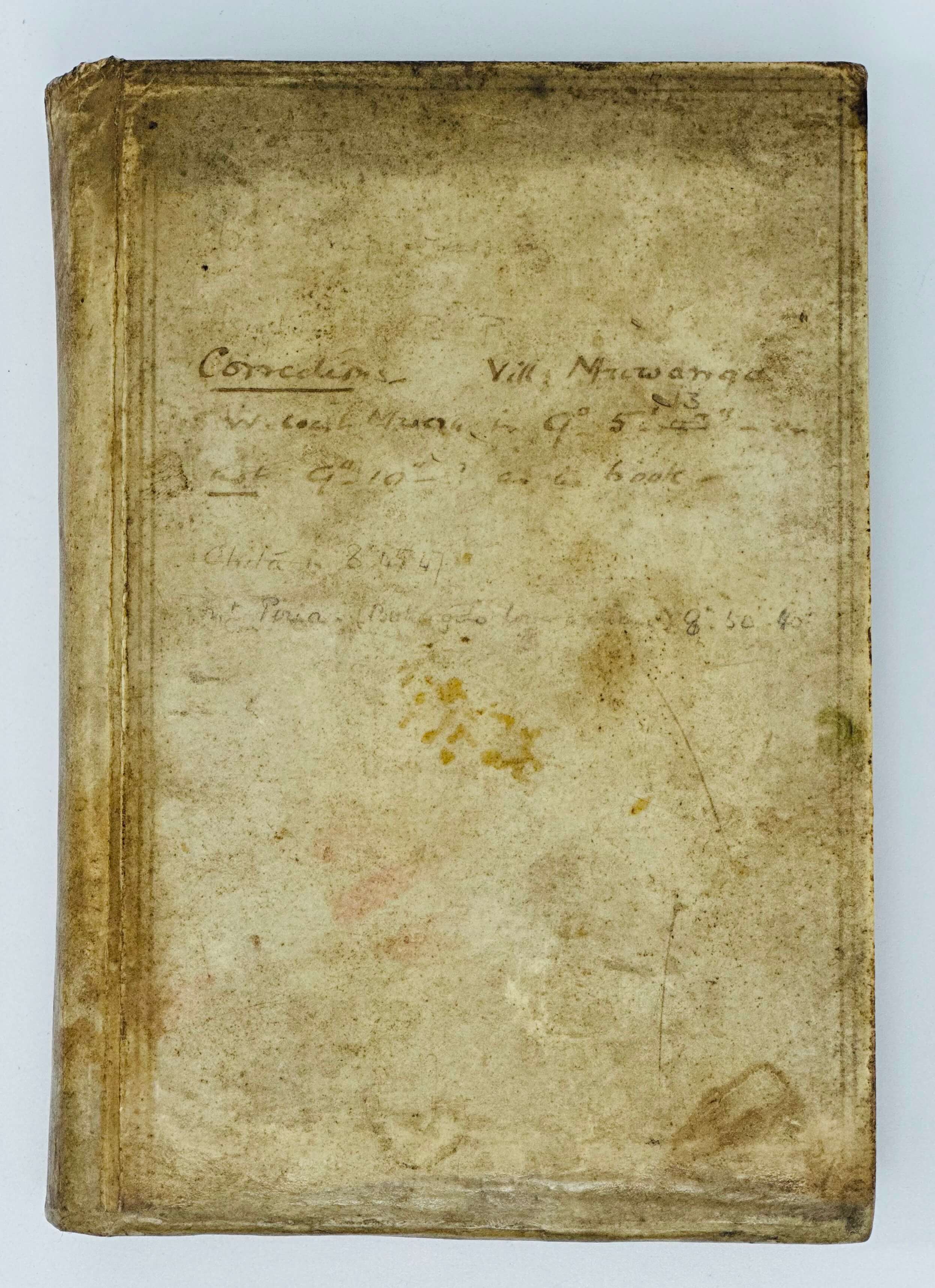

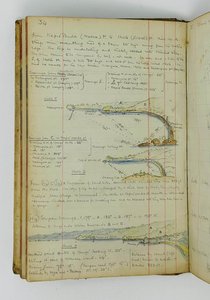

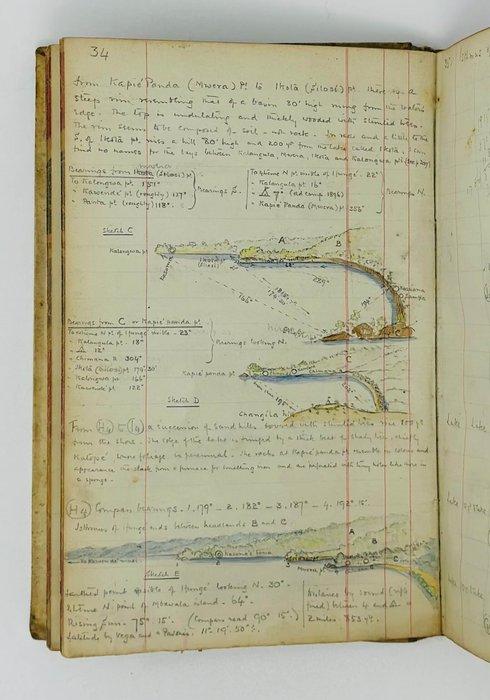

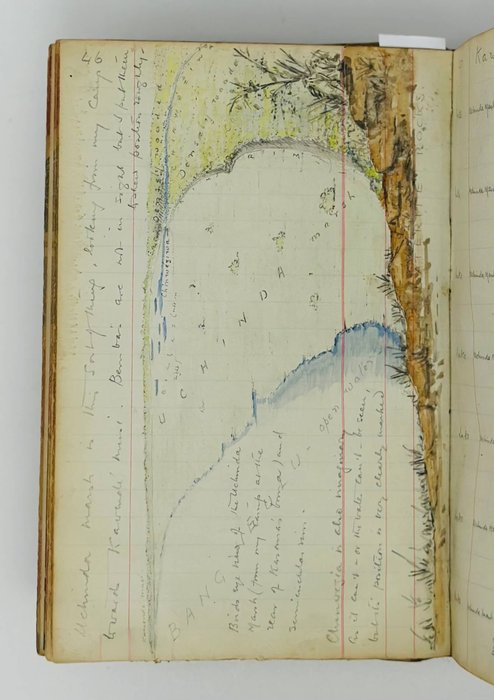

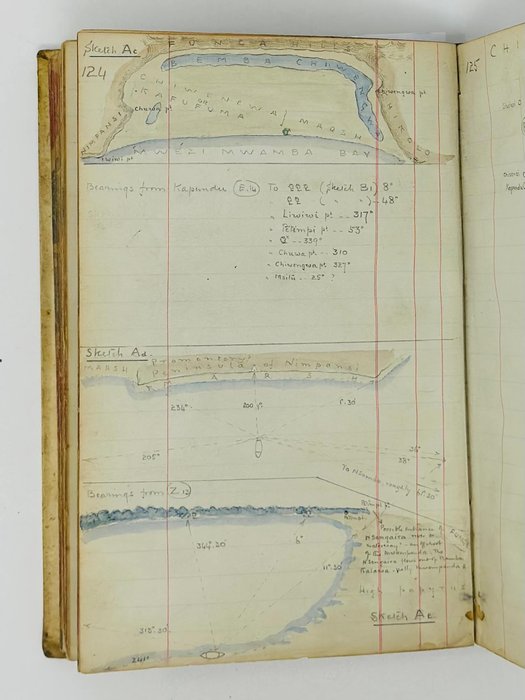

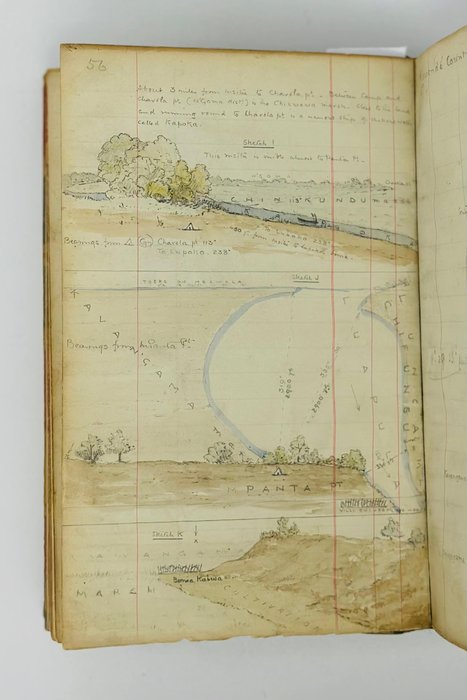

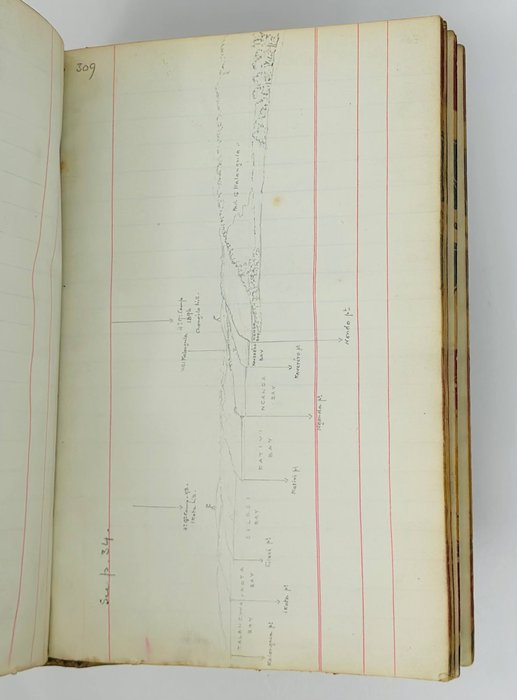

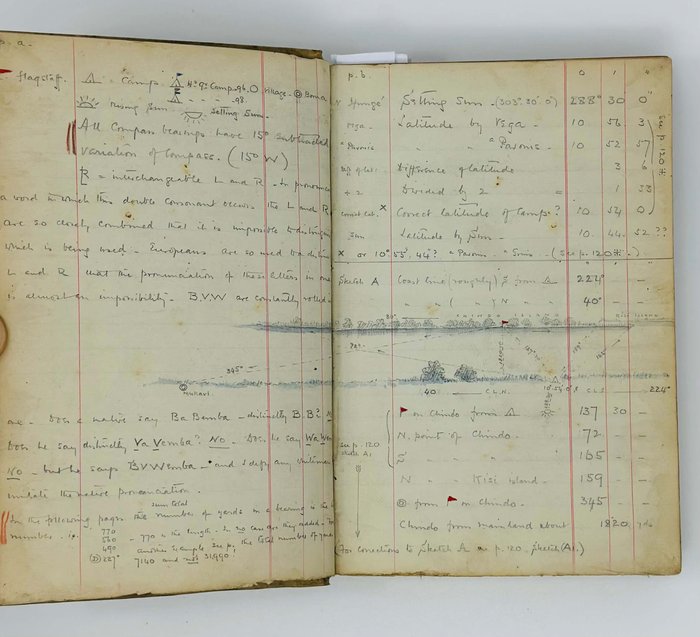

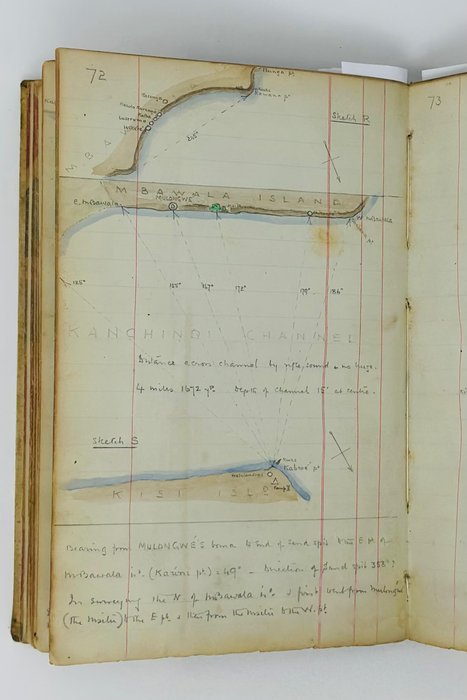

Octavo notebook, ca. 20,5x13,5 cm (8 x 5 ½ in). [3], 310, [1] pp. (numbered in ink in the left upper corners of the leaves), 25 blank leaves, 1 p. with notes at the rear. Text: pencil on lined paper. With over forty original pencil and watercolour maps and drawings in text (mostly numbered from “Sketch A” to “Sketch Av”), including four full-page maps. Period full vellum binding; marbled endpapers; upper and side edges marbled. Period ink and pencil notes on the front cover. Binding slightly rubbed and soiled, but overall a very good internally clean notebook with detailed sketches, many heightened in watercolour.

Historically significant, original manuscript notebook, documenting the first circumnavigation and comprehensive mapping of Lake Bangweulu in northern Zambia – one of the main wetlands systems of Central Africa, comprising the Lake itself, the Bangweulu Swamps and the floodplain. “The area has been designated as one of the world's most important wetlands by the Ramsar Convention and an "Important Bird Area" by BirdLife International” (Wikipedia). In 2021, the United Nations Environment Programme provided US$6 million to the Zambia government project to protect the Bagweulu wetland’s unique ecosystems (see more).

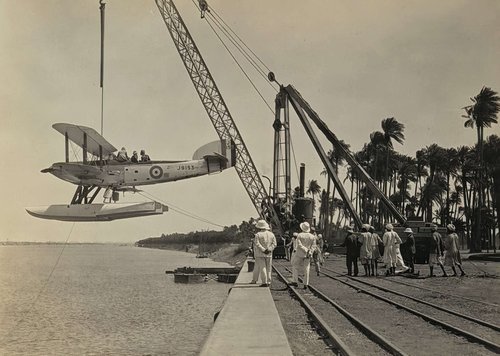

The first European to visit Bangweulu Lake in 1868 was David Livingstone. In 1873 he died of fever in the Chupundu village on the edge of the Bangweulu flood plain, “which makes the southern shore of Lake Bangweolo almost classic to geographers” (Prefaratory Remarks by the President to: Weatherley, P. Circumnavigation of Lake Bangweolo// The Geographical Journal. Vol. 12, No. 3, Sept. 1898, p. 242). In 1883, Liet. of the French navy Victor Giraud visited the lake, but it was an English military officer and big game hunter, Captain Cecil Poulett Weatherley, who first circumnavigated it in the summer of 1896. “<…> his examinations of the north-western and western sides constitute new discoveries” (Prefaratory Remarks…, p. 243). During the second trip in 1898, Weatherley completed his survey of the lake, correcting mistakes in the calculations of geographical coordinates, and produced the first comprehensive map of the Bangweulu wetlands. He also rediscovered the site where Livingstone’s heart was buried under a mpundu tree in Chipundu, which inspired the construction of the Livingstone Memorial on the site in 1899. Both Weatherley’s voyages around the Bangweulu Lake and the adjacent Luapula River took place on board the steel boat “Vigilant,” sent from England in sections and reconstructed on the Luapula River. Brief results of his expeditions, including the first detailed map of the Bangweulu Lake were published by the Royal Geographical Society: Weatherley, P. Circumnavigation of Lake Bangweolo// The Geographical Journal. Vol. 12, No. 3, Sept. 1898, pp. 241-259; Mr. Weatherley’s Surveys in the Bangweulu Region/Monthly Record// The Geographical Journal. Vol. 14, No. 5, Nov. 1899, pp. 56-563; Mr. Weatherley’s Map of Lake Bangweulu/Monthly Record// The Geographical Journal. Vol. 34, No. 1, Jul. 1909, pp. 86-88.

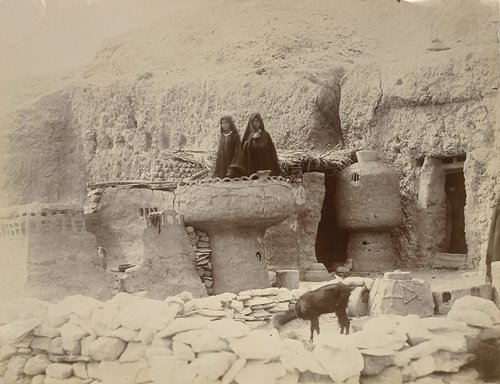

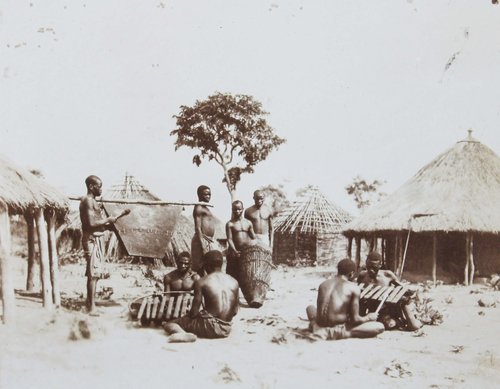

Weatherley also donated to the RGS a series of original photographs taken in the Bangweulu wetlands (Forty-Five Photographs of British Central Africa, by Poulett Weatherley, Esq., 1898/ New Maps// The Geographical Journal. Vol. 19, No. 1, Jan. 1902, pp. 119-120). The Society’s archive holds two of Weatherley’s illustrated diaries and a folder with original watercolours, created during his travels in Central Africa and specifically the Lake Bangweulu region in ca. 1889-1899 (see more).

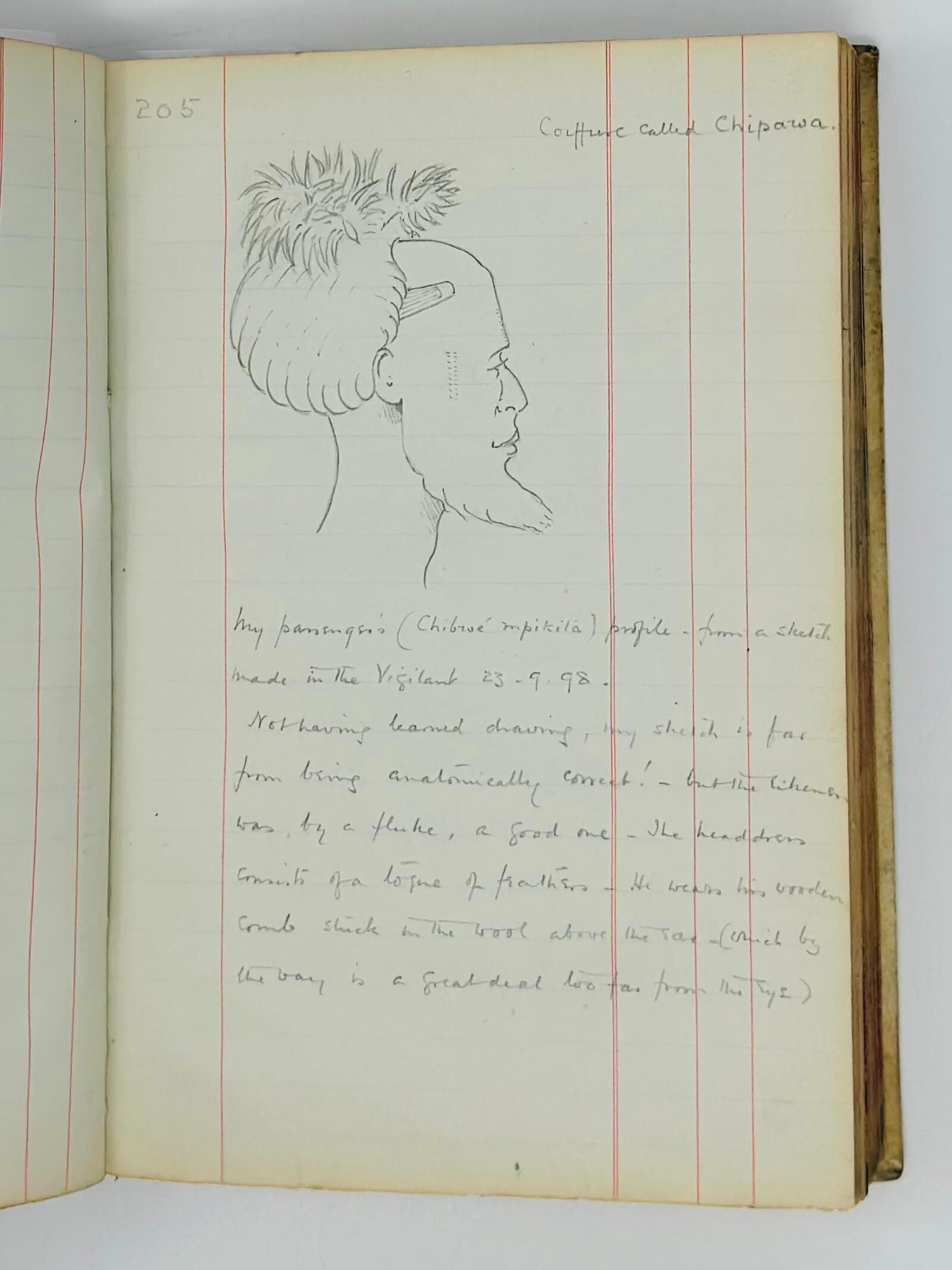

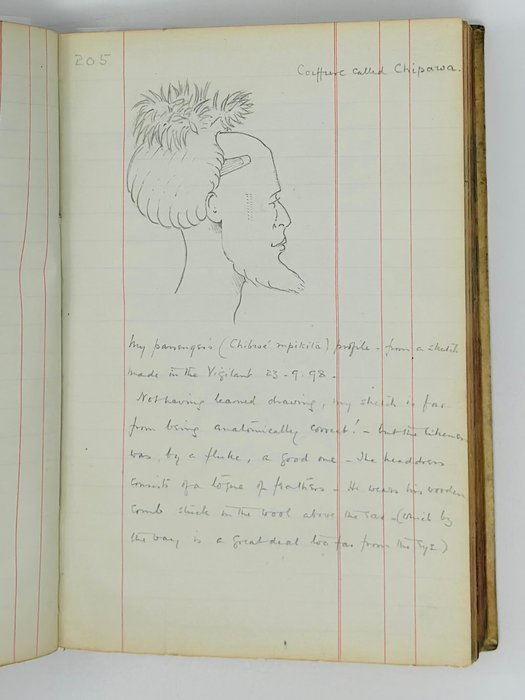

Our notebook evidently dates back to Weatherley’s second voyage in the Bangweulu region in 1898, with additions and remarks most likely made in 1899 (see pp. 51, 270). The manuscript starts with the survey of the Ifunge Peninsula on the west side of the Bangweulu lake and proceeds with the circumnavigation of the lake, moving counterclockwise. The next points of the survey are: Kawende Country (Uchinda Marsh, Miawa Channel, Kawan’gama Marsh), Kirui (Chilubi) Island, Kisi (Chisi or Chishi) Island, Mbawala (Mbabala) Island, Nkanga and Kasanga Marshes in the Luena River estuary, Kasanga Marsh and Nsangwa Island, Bemba Chifunawuli (Lake Chifunabuli), Lake Kampolombo. The last part of the notebook contains the survey of the Luapula River throughout its course up to its flowing into Lake Mweru. The survey text includes detailednotes on compass bearings, longitude and latitude, distance to the lake from survey points (in yards), and occasional geographical features (“sand hills,” “marsh,” “high papyrus patches,” &c.). The additions and remarks comment on the natural resources and terrain of a specific part of the Bangweulu wetlands, native tribes (Wena Kawende, Mieri Mieri, Vavemba, Wena Lullnda, Wallsi, Wena Kisinga, Wena Gnumbo and many others), history of their settlement in the area and relations with the neighbours, main occupations, preferred methods and styles of tattoos, hairdos and teeth filing, &c. Pp. 61 and 74 contain the lists of “Names of some African families.” There are also notes and critical comment on the surveys by Weatherley’s predecessors who travelled to the area – Giraud and Sharpe (pp. 212, 276, 278), a passage on the correct pronunciation and spelling of native names (pp. 304-306), &c.

Six large full-page watercolour sketches show the Uchinda Marsh, the coast of the Kirui Island (from Karampwa Point to Kifofu Point, from Kasonga Point to Itundu Point), Kanchindi Channel between the Mbawala (Mbabala) and Kisi (Chisi) Islands, Nkanga Marsh, and Luela River valley (from its headwaters in the Chirengwa Hills to the confluence with the Luapala River). Two large pencil sketches are 1) a coastal profile of the Ifunge peninsula with the indication of the bays, points and two of Weatherley’s survey camps; and 2) “View of the S. half of Kisi Isd. Looking towards Kabwe pt…”

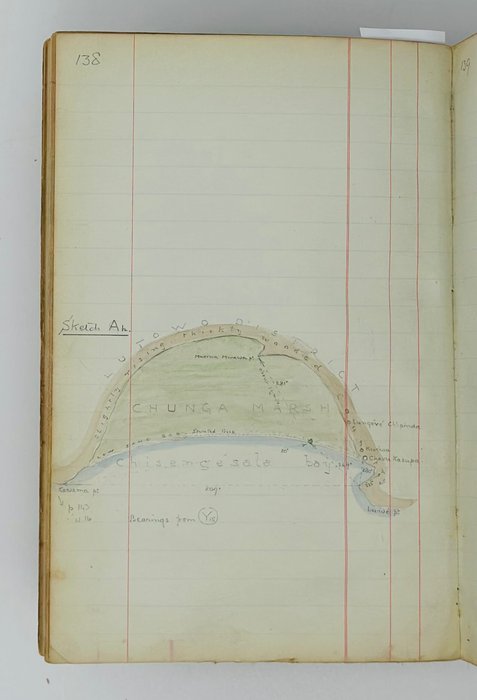

The smaller maps and sketches show various locations on the Ifunge Peninsula (“Changila Hill 80’ high on which was camp in 1896,” the shore from Kasoma to Ikota/Silosi point, Kelongwa point, &c.), Miawa Channel between Mbawala Island and Kawende Musi on the lake’s southern shore, the mouth of the Luapula River and Panta Point, Kasamba Marsh, Nsangwa Island, Chindo Island, Bemba Chiwengwa, the shores of Lake Chifunabuli section, Chisengesale Bay and Chunga Marsh, the area around Lake Kampolombo, Luapula River (Vaka Vaka Inlet), and others. Two pencil drawings depict a “Coiffure called Chipawa” (p. 205) and “Chiveka – a Muemba boy” (p. 207).

Overall a historically significant, content-rich original source on the boundaries, terrain, water levels, &c. of the Bangweulu lake and wetlands and the history and customs of the local tribes at the time of exploration of Bangweulu in the late 19th century.

Excerpts from the notebook:

P. [3]. Funge. A noticeable feature about this isthmus is the extreme whiteness of the sand. At a distance it has the appearance of snow. It seems composed entirely from white, almost transparent quartz. There are few coloured pebbles, and shells of any sort are extremely rare. <…>

P. 8. I have called Ifunge all through my survey, an isthmus, but it is more properly speaking a peninsula stretching north, shaped something like a stalactite – its base near Kasomai being very broad, ad apex at Nsombos narrow. All round the N. and N.W. of Ifunge is a vast marsh caused by the junction of three big marshy rivers to the N.W. of Bangwaulu, i.e. the Mwampanda, the Liposili and the Lufubu…

Pp. 12-13. The natives in this part, as in most other parts, of C. Africa, have a love for names – no puddle, no scrap of mud, no tiny collection of reeds or papyrus is too insignificant for a name. The waterways through the Bengweulu marshes have each a name and these waterways are countless. Similarly in the Luapula – the channels on either side of an island had invariably each a name. Every scrap of mud shewing above water in Bangweulu had its name. <…> This plethora of names gave me much trouble. It was so hard at times to find out what was really what!

P. 38. The Wena Kawende are undoubtedly the best lot of natives on the coast and vicinity of Bengweulu, with the exception of the Vavemba to the north. Their rightful Chief Kawongo is an extremely nice old man in may ways but is unfortunately greatly addicted to the undue consumption of wengwa, i.e. <…> native beer. Kasoma, one of the subchiefs, taking advantage of this weakness on the part of his senior chief, by a coup d’etat assumed the role of paramount Chief with little or no fighting. Kasoma is exceedingly intelligent – almost too intelligent from his intercourse with Arabs – energetic man, and an elephant hunter.

Pp. 50, 52. After Mewenge had in a drunken fit nearly brained me with an axe on my first journey, he shrieked out to me ‘Kasoma is mad! He will want to fight you!’ but when I made the acquaintance of Kasoma I found the madness and want of fight lay Mewenge’s side of the house. Mewenge is the most pleasant of natives when sober, but when drunk – his usual condition six days out of seven, he is a veritable demon. He also consumes vast quantities of hemp and tobacco. Whilst writing this (19.7.99) news comes that Mieri Mieri has attacked Mewenge but has got considerably the worst of it.

Pp. 52, 54, 64. The Wena Kawende file both upper and lower front teeth into sharp points. They tattoo the mulunku – i.e. a line of dots from below each ear to the shoulder and one down the nape of the neck. The mulunku is also tattooed on chest and stomach <…> There are two modes of tattooing – little incisions and small raised dots. <…> The incisions – about this length – are made with a sharp bit of iron or arrow point, charcoal being then rubbed in. <…> The dots are made by a needle (native, which is about twice as thick as a big darning needle) being inserted under the skin which is then cut across and charcoal rubbed in, the result being a tiny round bump…

P. 60. Kirui is undoubtedly the largest, most important, most thickly populated, most cultivated and, out and away, the best wooded, of the islands of Bangweulu. From Panta pt. almost to Kirui Isd. one coasts along a high wall of dense papyrus, with here and there a mud bank on which fishermen erect temporary shelters.

P. 76. Kisi Isd. is fertile but exceedingly poorly wooded. The few trees that remain are being cut down year after year and no attempt of course is made to ensure others taking the places of those felled. Wood for cooking purposes is now brought from Kirui ad Funge.

P. 82. The Wena Lullnda have rather elaborate tattooing all over the stomach and down the right and left sides. <…> They extract the two lower front teeth and file the ^ gap between the two upper ones. To return to the tatooing, they have the two perpendicular lines of incisions on the temples to the cheekbones.

P. 122. Bemba Chifunawuli. This lakelet was discovered by me in 1896. It is somewhat similar to Lake Kampolombo but it is not so broad. The Gnumbo country, which extends the entire length of Chifunawuli (see p. 120) is very thickly populated near the lake. The Wena N’Gnumbo are unwarlike they are agriculturalists in a mild way – not doing more work than they can keep – and do a little wood carving. There are a good many sheep – the broad tailed kind – and goats in the country, but no cattle. They are of course great fishermen and make many canoes. They are inveterate smokers of both tobacco and hemp. To the latter pernicious habit I attribute their cowardice. Wherever one finds hemp grown and smoked in enormous quantities, the natives are all nerves and fit for nothing.

P. 132. It is curious to remark the number of natives with bad and decayed teeth. Filing in most cases utterly destroys them. A good, perfectly sound set is certainly the exception in these parts where so much filing is done, and the Central Africans’ teeth will not bear comparison for a moment with those of the natives of Southern Africa…

P. 162. The southern end of Chifunawuli is practically a vast bog. This is no doubt due to the mass of decomposed vegetation etc. brought down by the Mwanna [Nalonga?] R. – or properly speaking, Tandasi R. which enters the lake at the S.W. corner. The water at this part and along the entire length of the S. end is barely 6 inches deep whilst the decomposed matter is from 8-10 feet in depth. As the Vigilant was pushed through it, myriads of tiny bubbles rose up through the mud and exploded on reaching the surface with a hissing sound, emitting a vile stench. It was really as if we were travelling through a black or rather green brown lake of soda water. The surface of the water all round the boat for a distance of 50 yds. was a mass of exploding bubbles and though the stench was well nigh unbearable, I had to sit for an hour in it till my [Alonpa?] crossed to Ifunge to fire a rifle so that I might ascertain the distance across…

P. 214. Luombwa River. This river rises in the Isume Mts. which are not more I should say than 30 miles as the crow flies – if as much – from Luapula. It is a delightful little river with long deep reaches, in which one gets excellent fishing, and country on either side alternately plain and forest country. It is a perfectly ideal picnic river…

P. 216. Mumbotuta Falls. These falls are undoubtely the sight of the Luapula. The river which is about 500 yds at this point is cut in half by a ‘fault’ which crosses the Luapula diagonally. The first sheer fall is about 15’, below which is a broad flat platform of rock. Ther for about 300 yd is a steep sloping mass of black rocks which are almost hidden amid a thundering chaos of great waves, heaped up masses of foam and clouds of spray…

P. 280. [Luapula River]. These red cliffs are, with the exception of Mumbotuta Falls, the most remarkable sight of the Luapula. I have seen many ref cliffs, but not such an extraordinary red as these. It is not red by cavalry scarlet and the effect is marvellously beautiful. Hese cliffs are isolated and form the most striking landmark of the Luapula from Bangweulu to Mweru. The nature of the soil of which they are composed is unknown to me, It is exceedingly friable and the slightest weight sends masses into the water below.

P. 218. Mwyan’gashe river. Most disappointing in every way. I hoped by the appearance of its mouth to find <…> Luombwa. At the outset I had to leave the Vigilant and take to a small canoe just capable of holding two. <…> After having had to get out and drag the canoe for a couple of miles through a series of rapids too shallow to pole up, we abandoned the canoe. <…> Not a single village or an animal of any sort owing to the myriads of horse flies and tsetse which enveloped us in clouds throughout the daytime. The only way we got a little peace was to sitting in the pungent smoke of damp wood…

Pp. 303-304. The parts of the Luapula I did in the Vigilant and canoe are as follows:

Bangweulu to the sudd block,

Katutwe to the Kundalira rapids,

Kalonga to head of the Johnston Falls,

The foot of Johnston Falls to Mweru.

The part of Luapula I did not do at all is from the sudd block to Katutwe as my boat had not been repaired and I could not get a canoe – possibly 8-10 miles.

I have unfortunately mislaid the paper on which I wrote down the bends of the Luapula from Panta Pt. to the crossing spot on Kapata.

Captain Cecil Poulett Weatherley “was one of the early explorers of <…> Northern Rhodesia, the Belgian Congo and Tanganyika territory. He was the discoverer of the source of the Congo, and was the first white man to circumnavigate Lake Bangweulu. For his work in Central Africa he received the Cuthbert Park grant of the Royal Geographical Society.

His method of survey was characteristic. When shooting along the Luapula he took compass bearings of all the windings of the river. Every night he posted men with rifles at important points, and by timing the interval between the flash of the rifles and the hearing of the report determined the distances between the points by calculating sound to travel at 1,111 feet per second. So accurate was he that when the distances were later mapped by trained surveyors no serious errors were discovered in his maps.

Captain Weatherley served through the Zulu War of 1879, in which his father and brother were killed on the same day. Five years later he took part in the Nile Expedition, while in the Great War he served against the Senussi, and afterwards with the Australians on the Western front…” (Explorer’s Death: Discovered the Source of the Congo// Liverpool Daily Post. Monday, August 15, 1932, p. 6).