#O9

[Ca. 1823-1829]

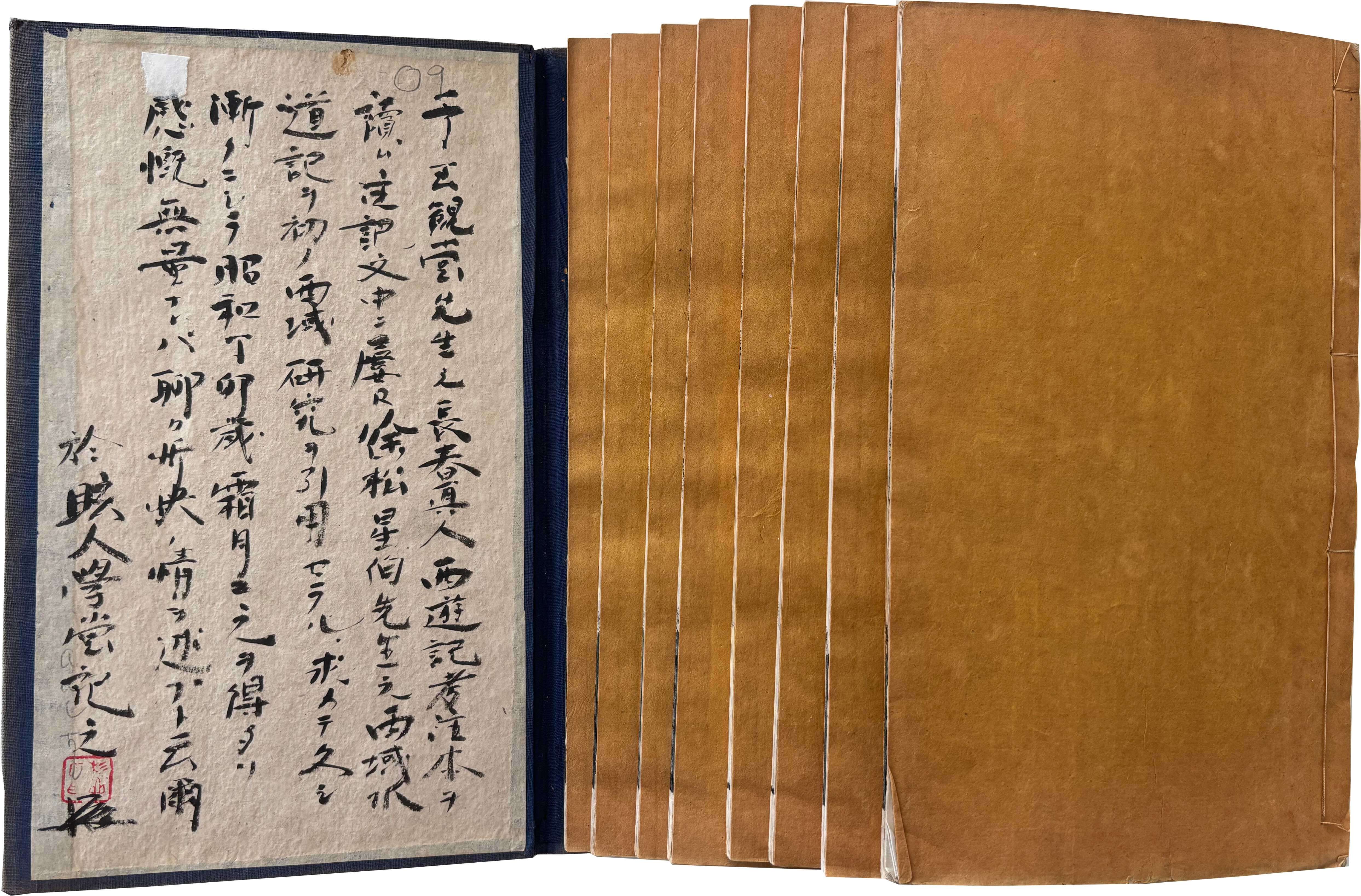

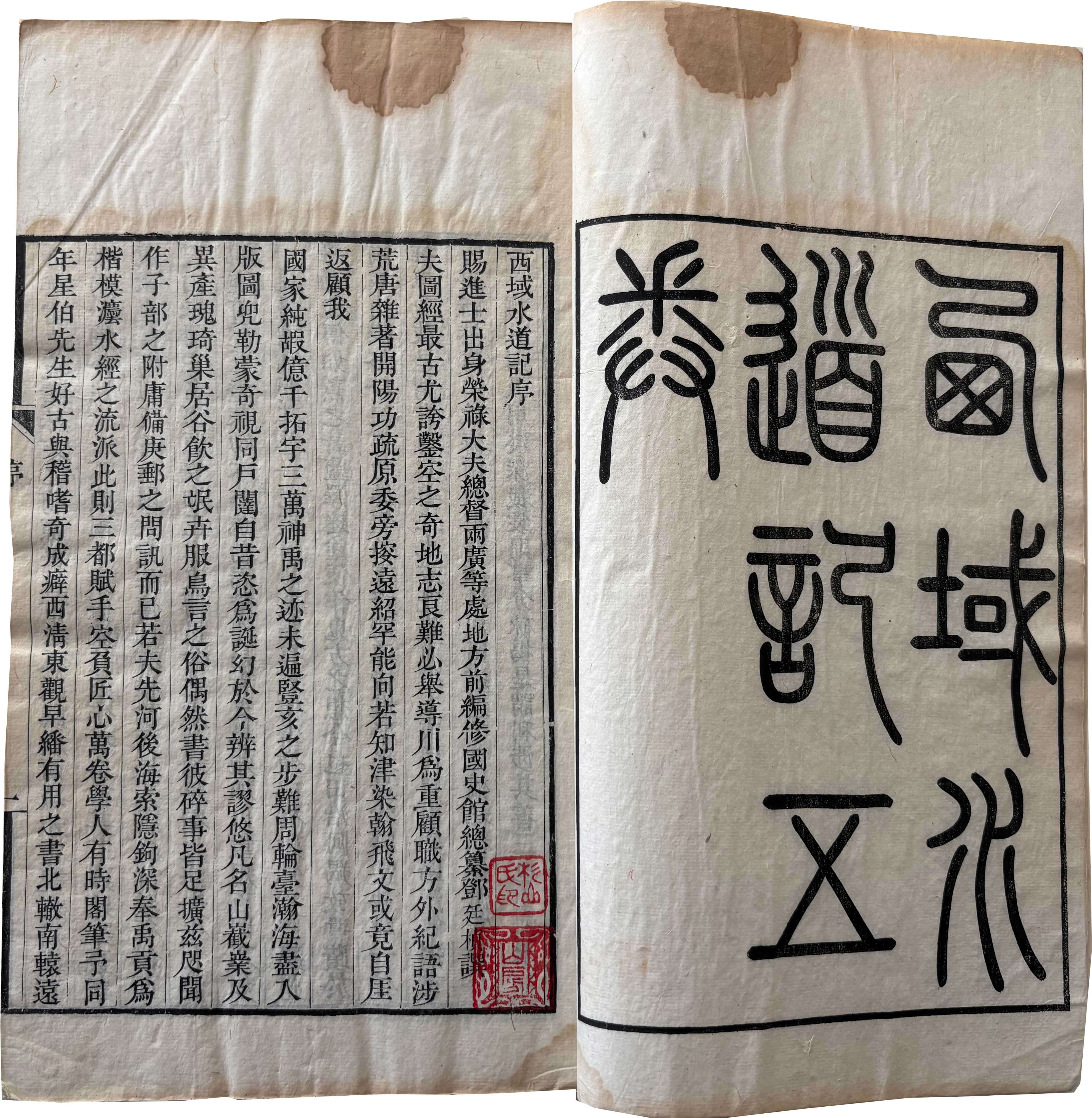

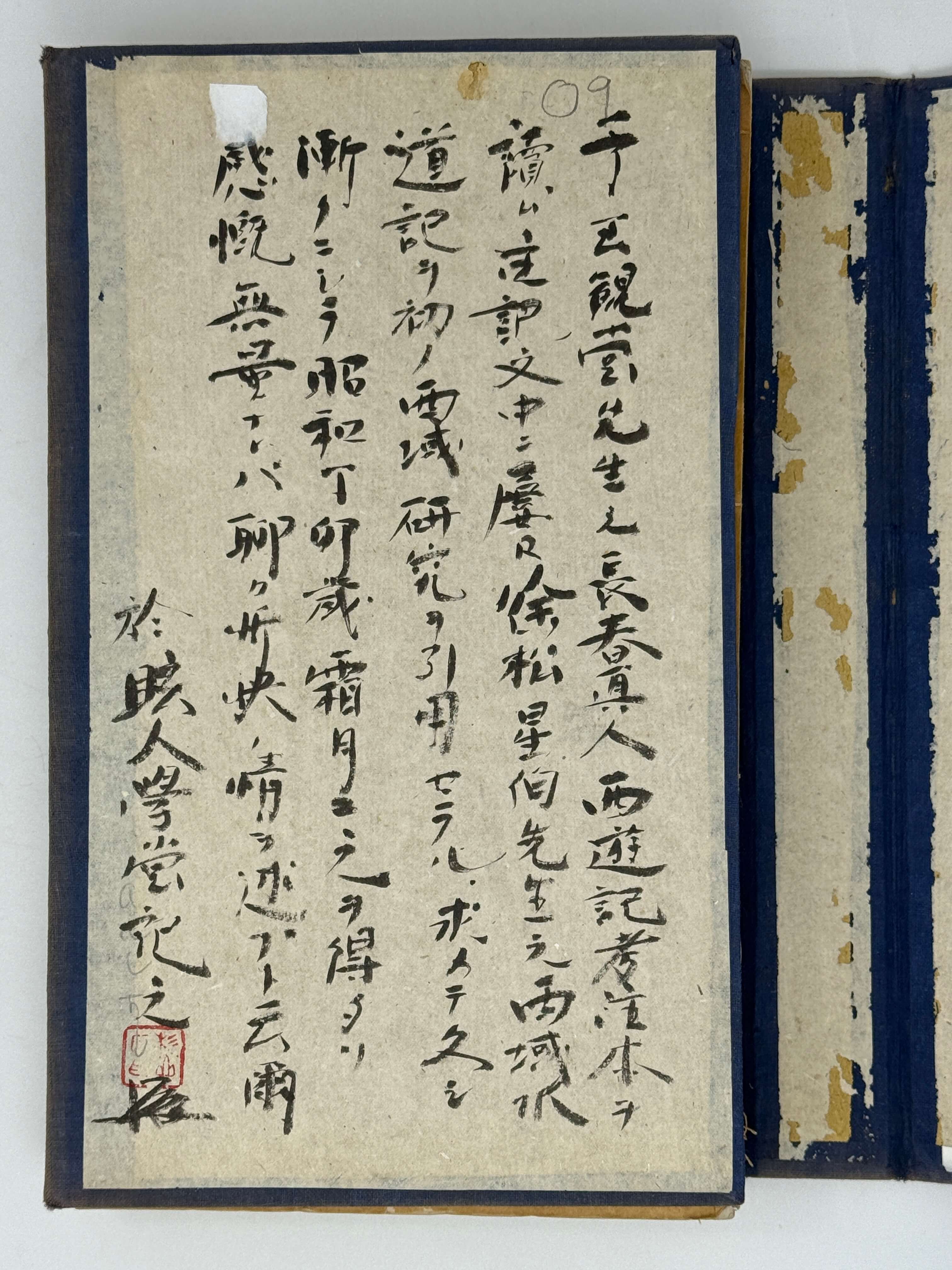

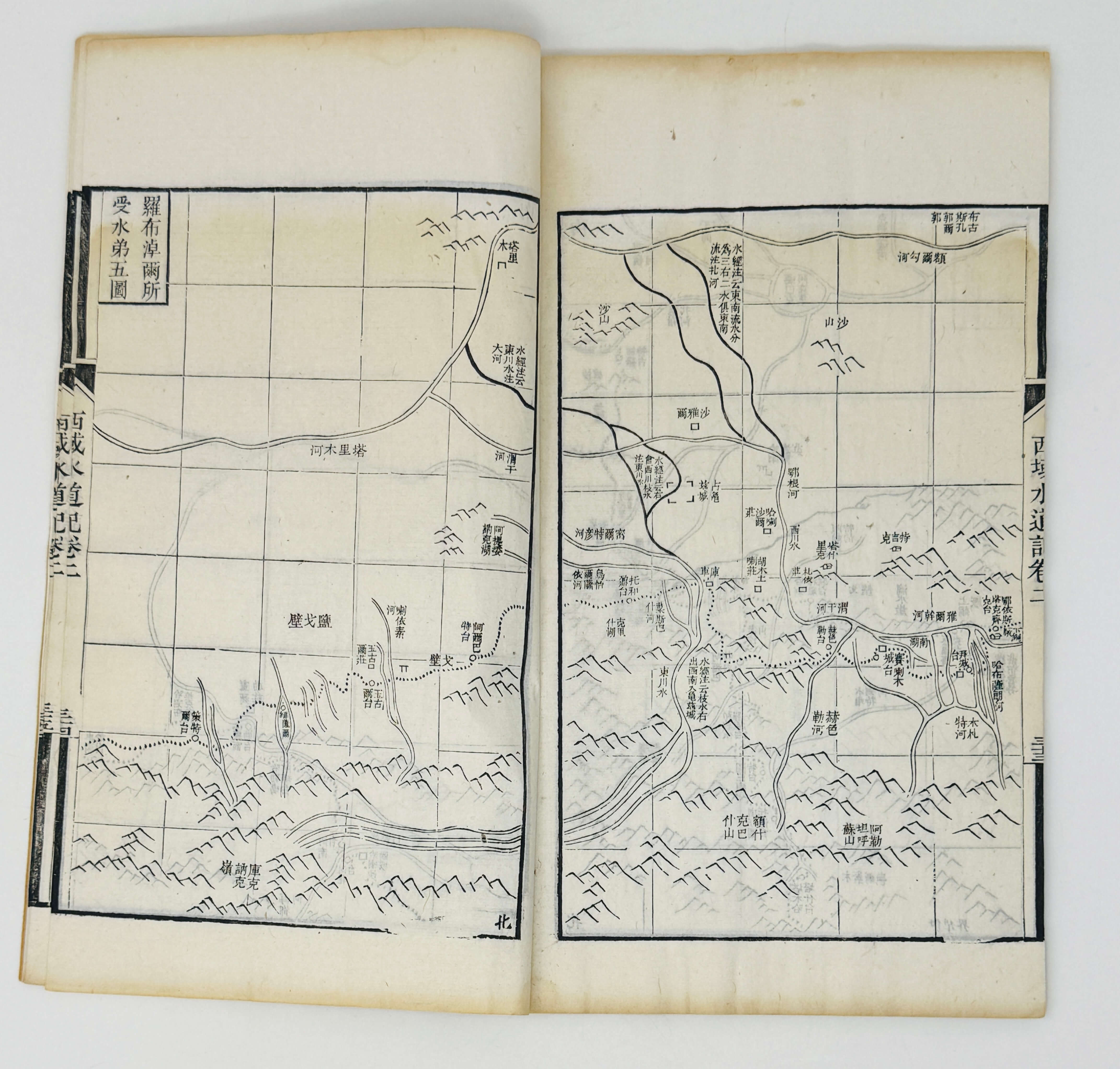

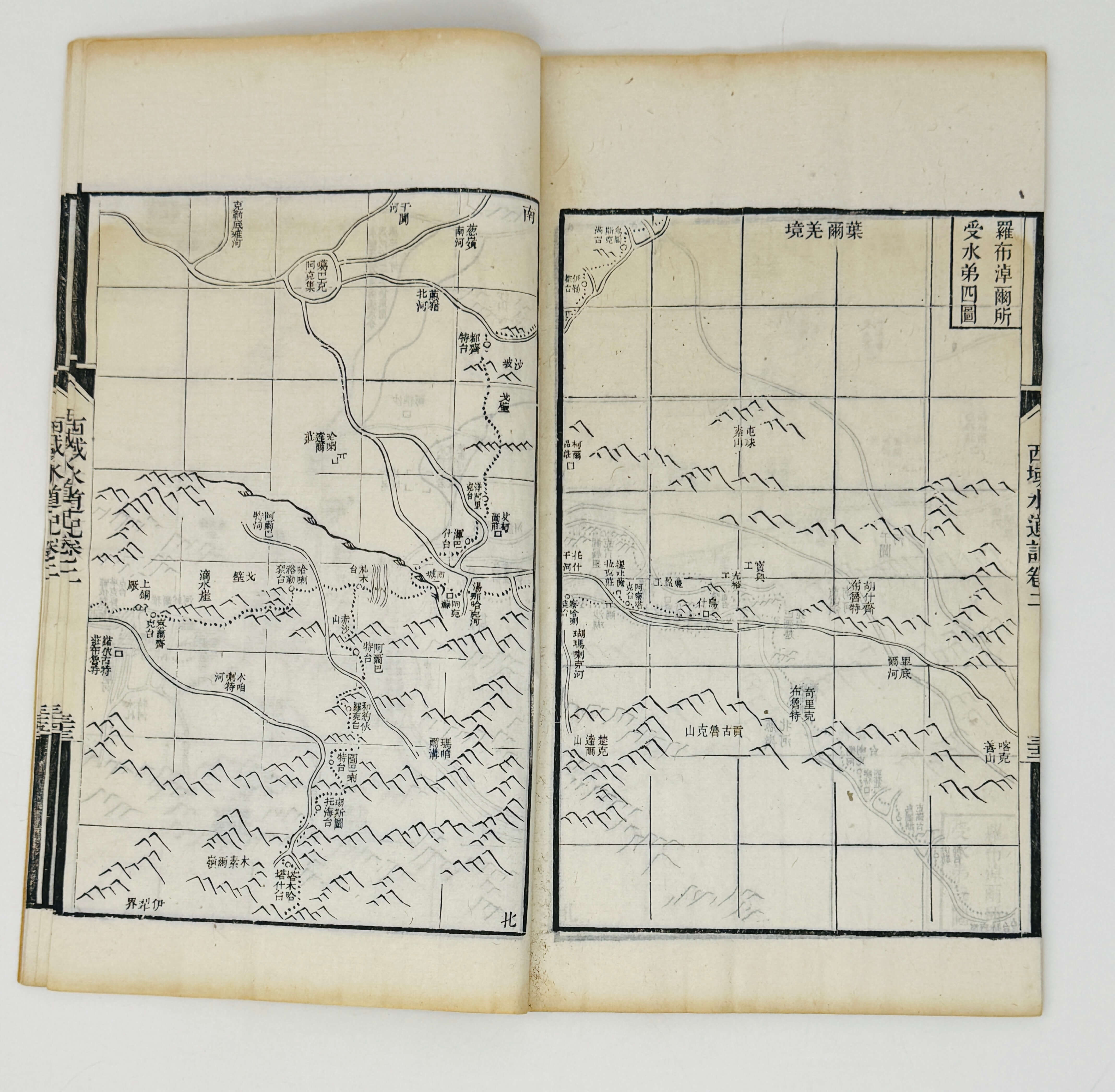

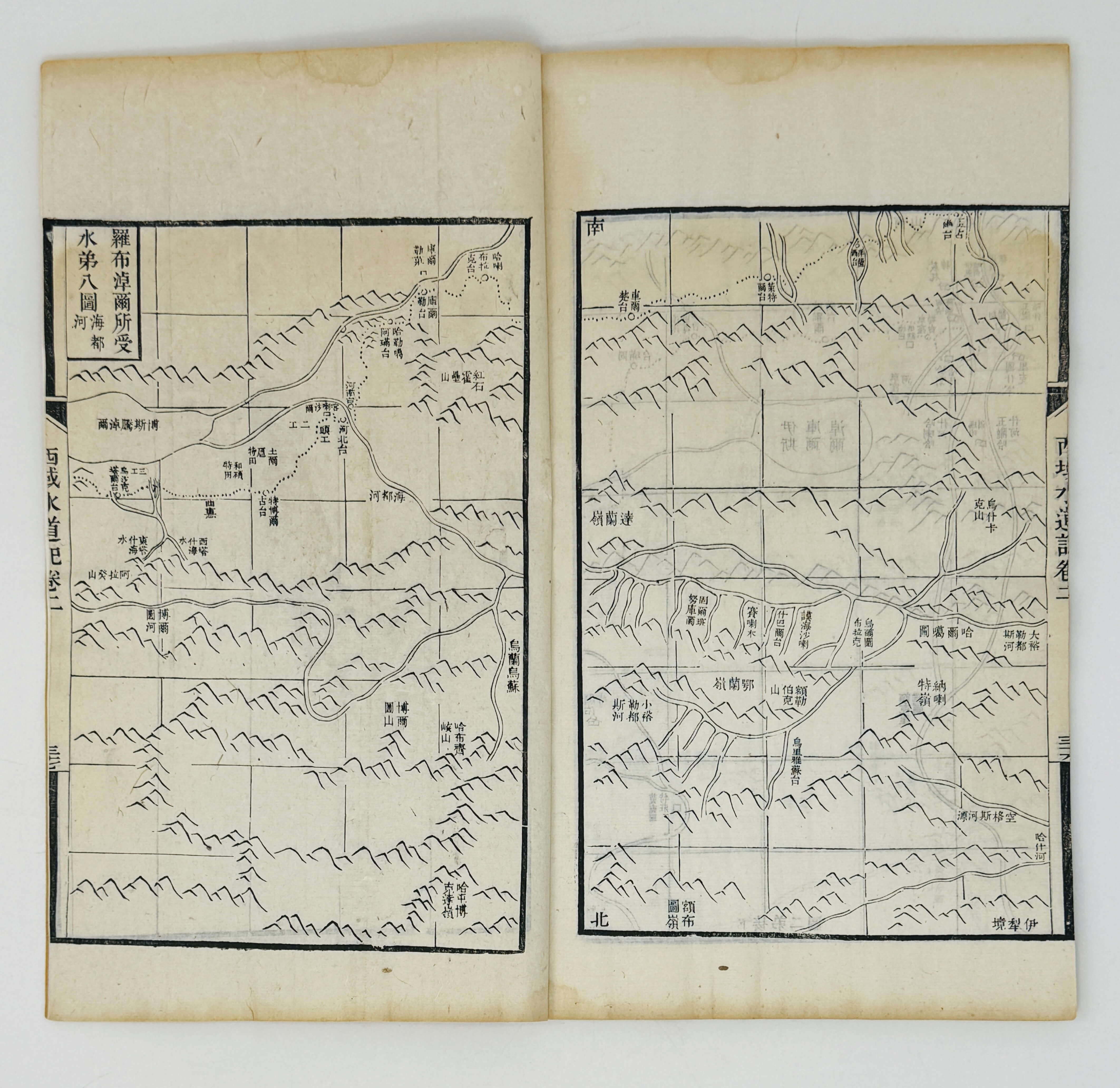

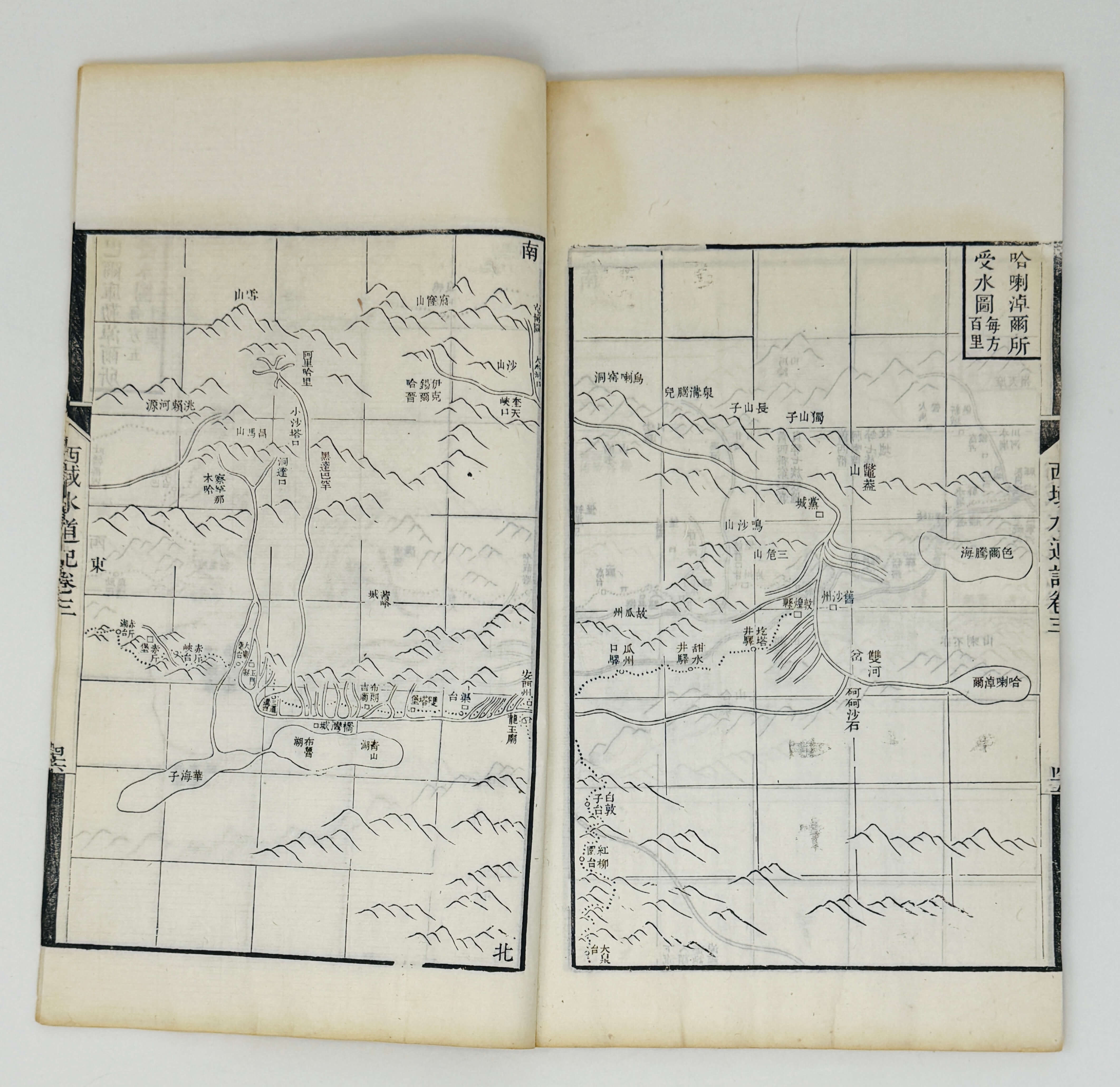

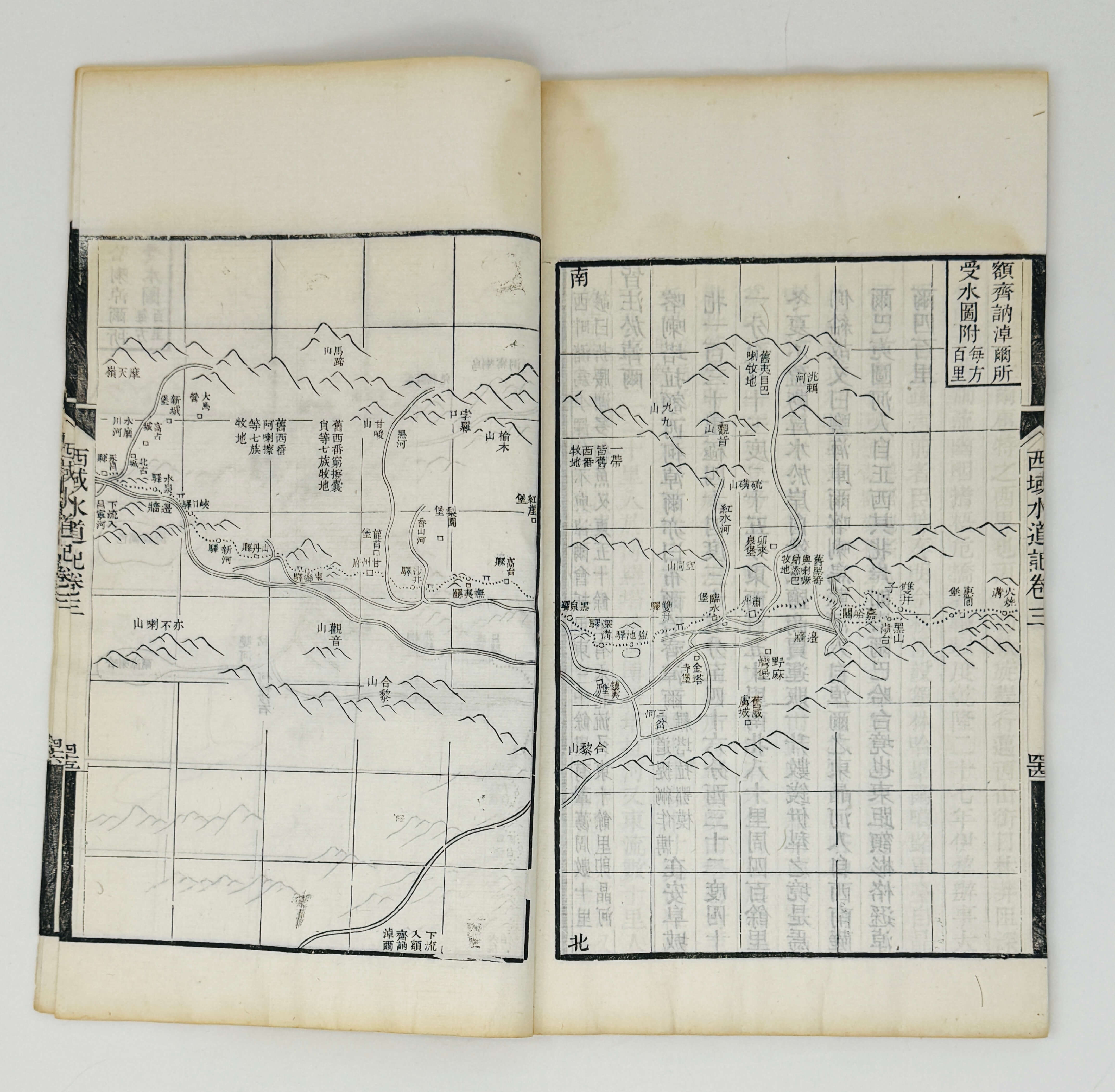

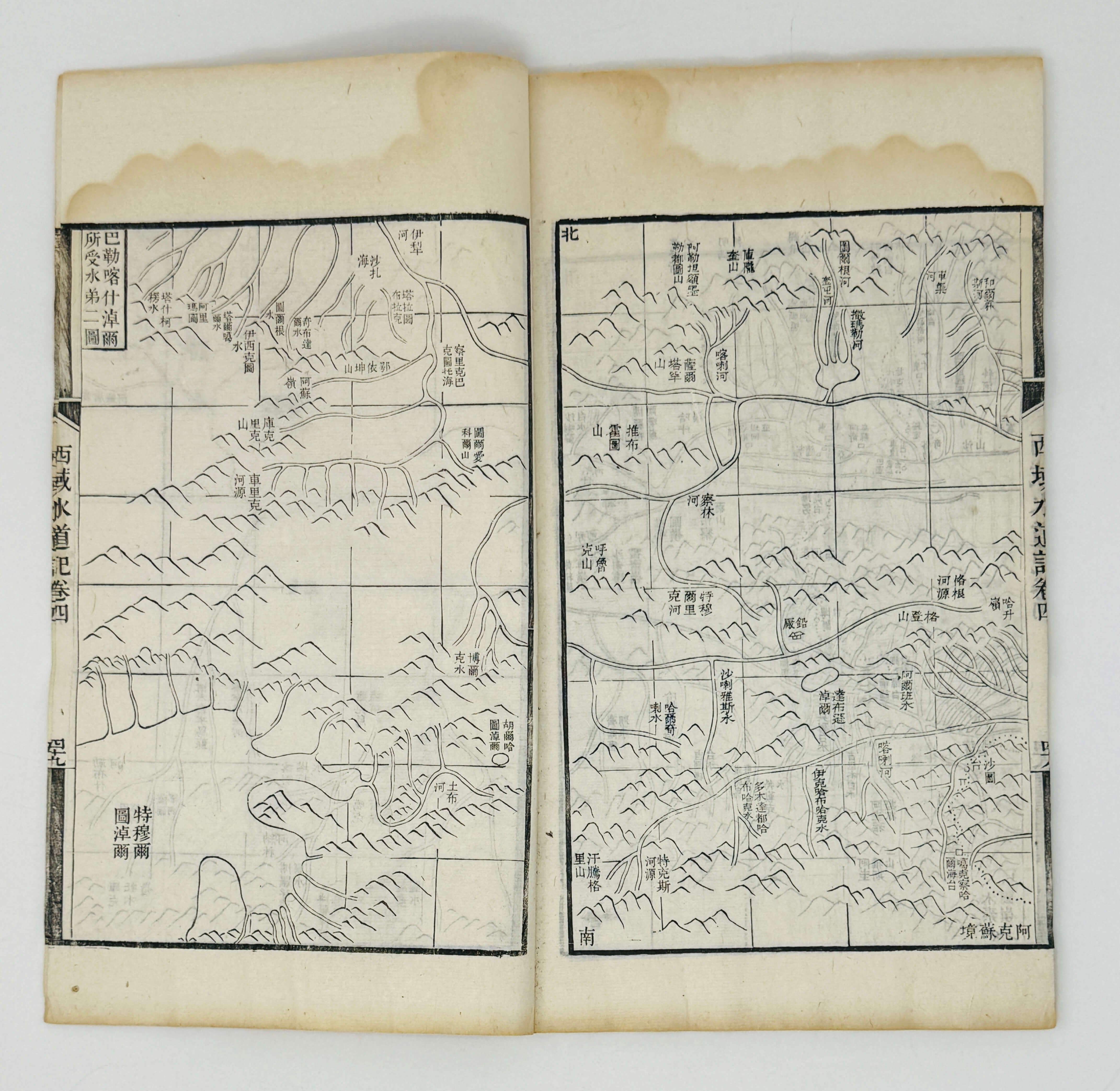

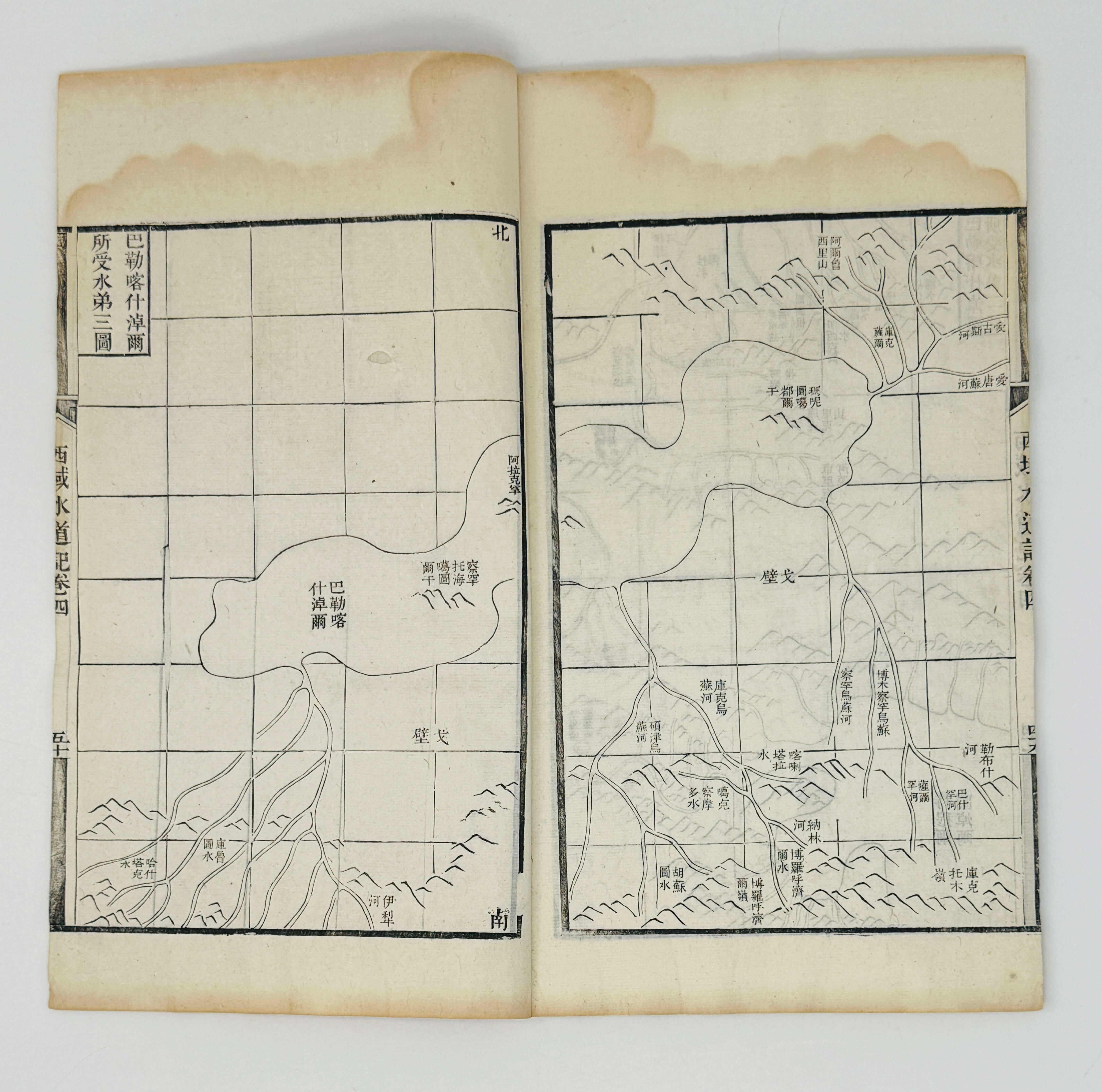

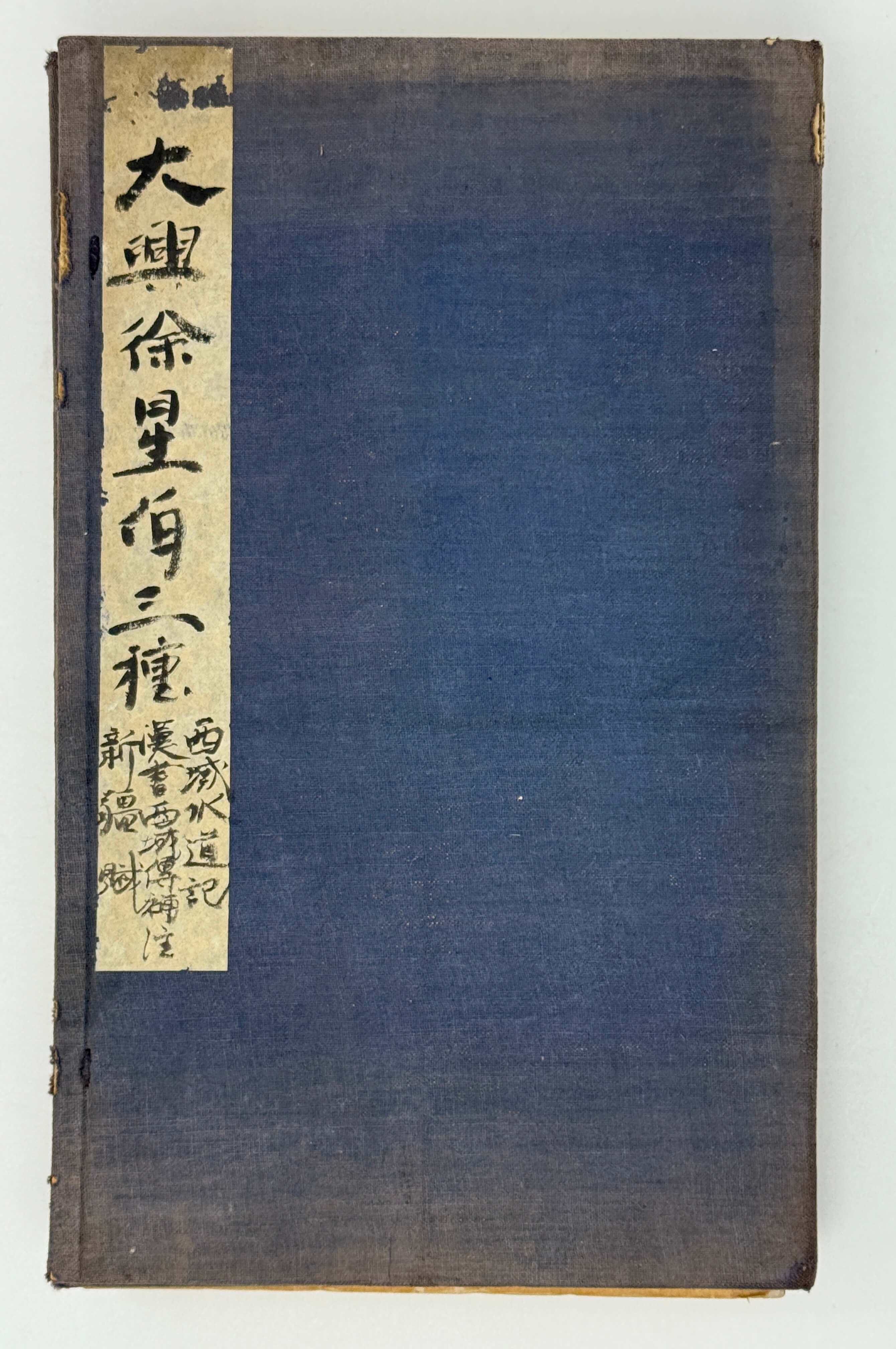

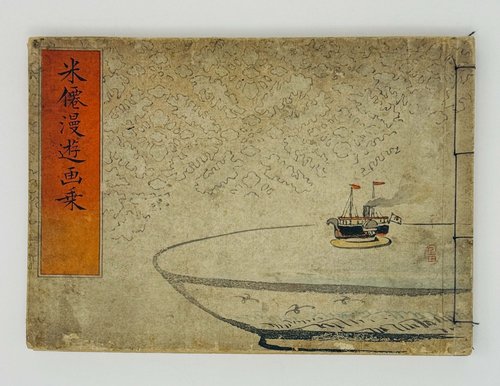

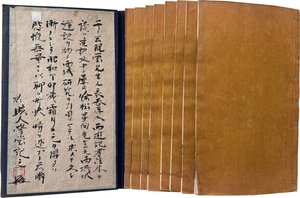

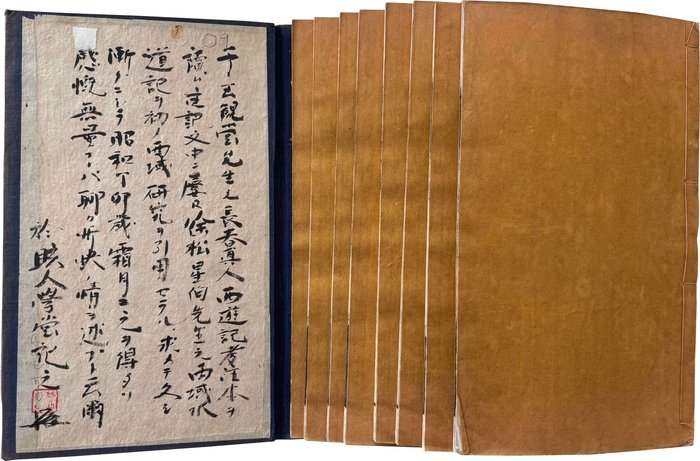

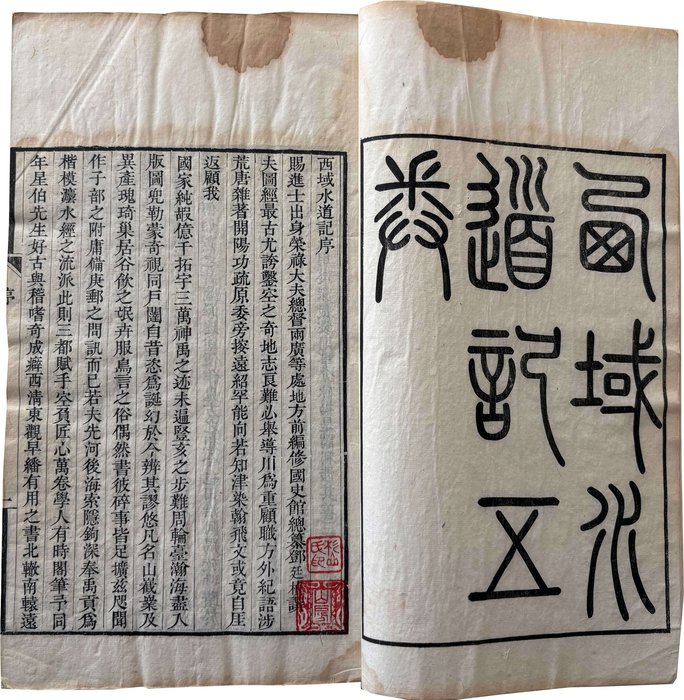

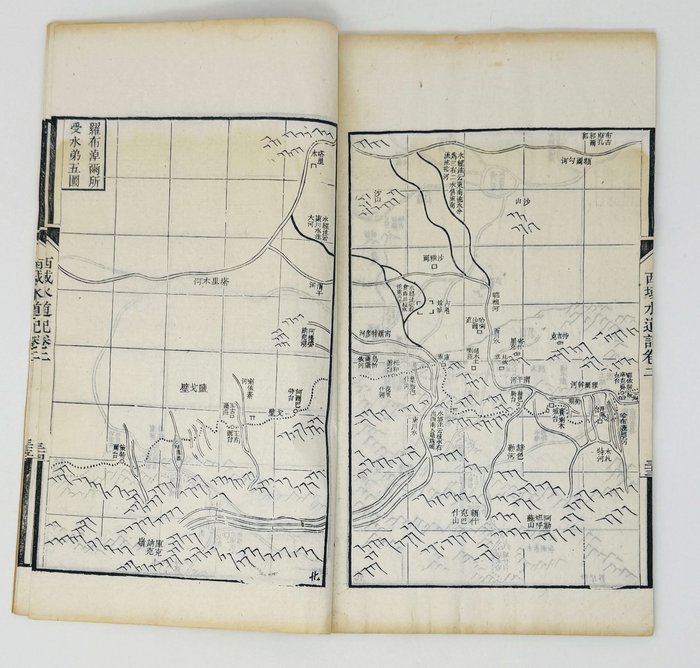

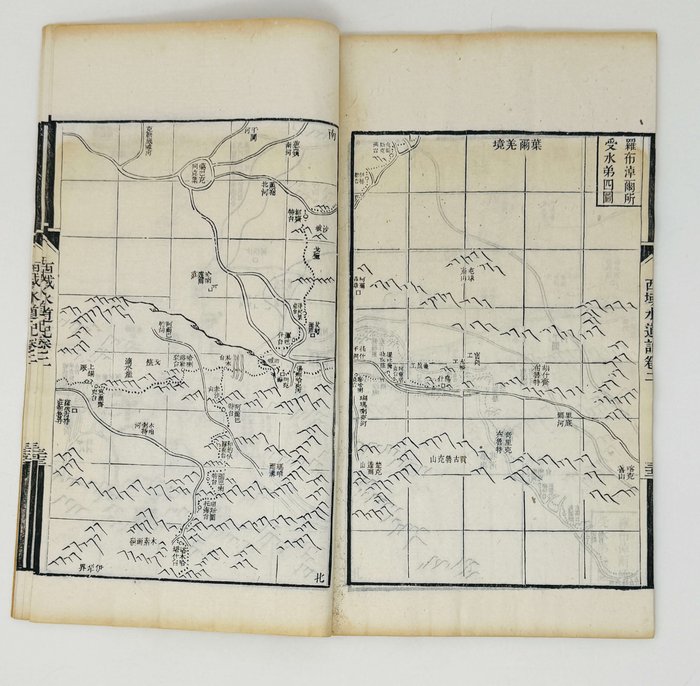

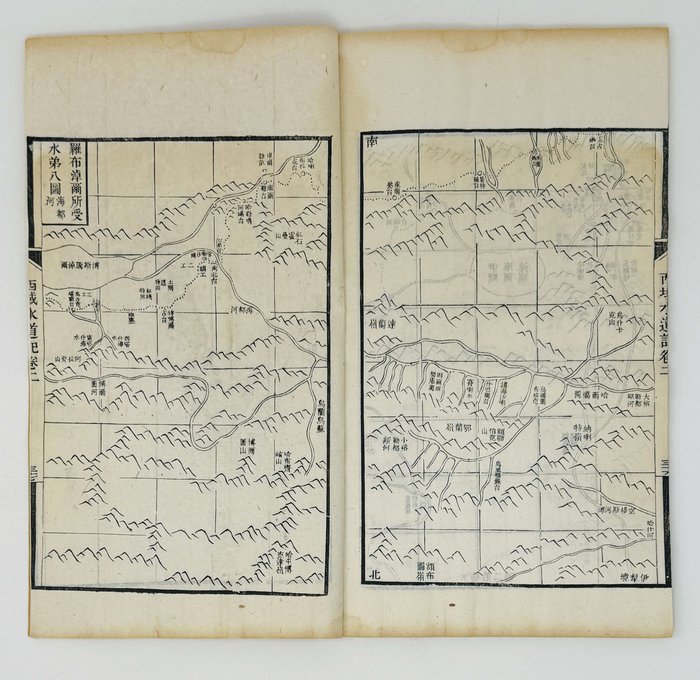

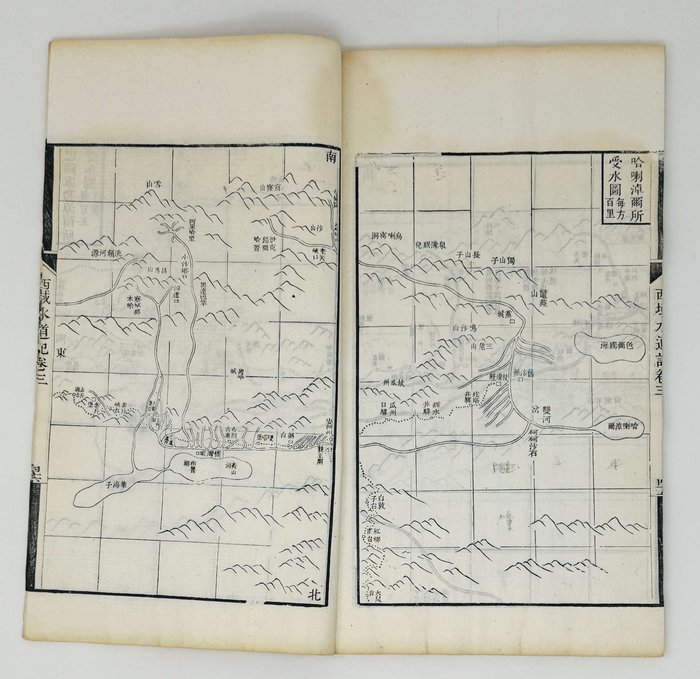

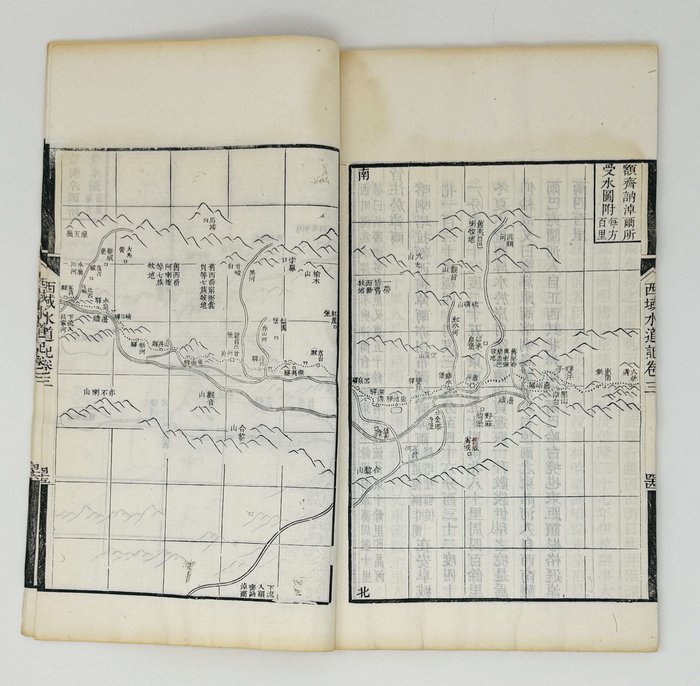

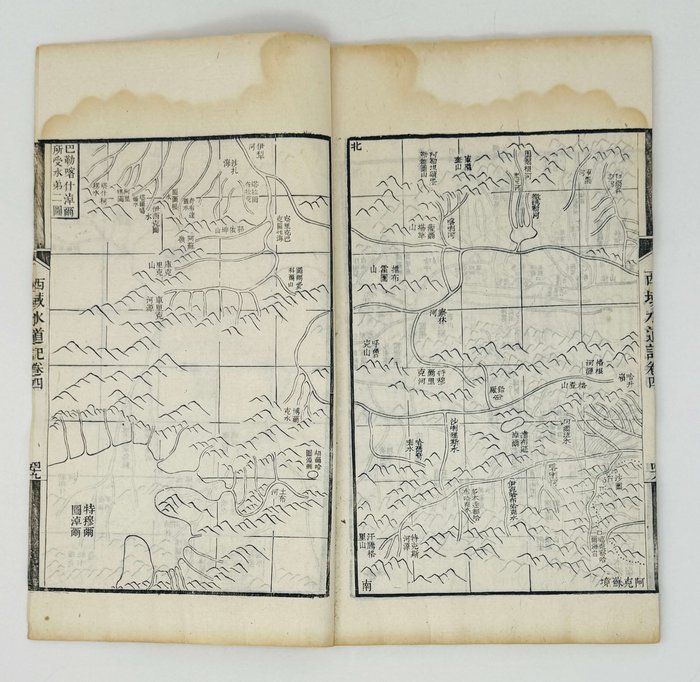

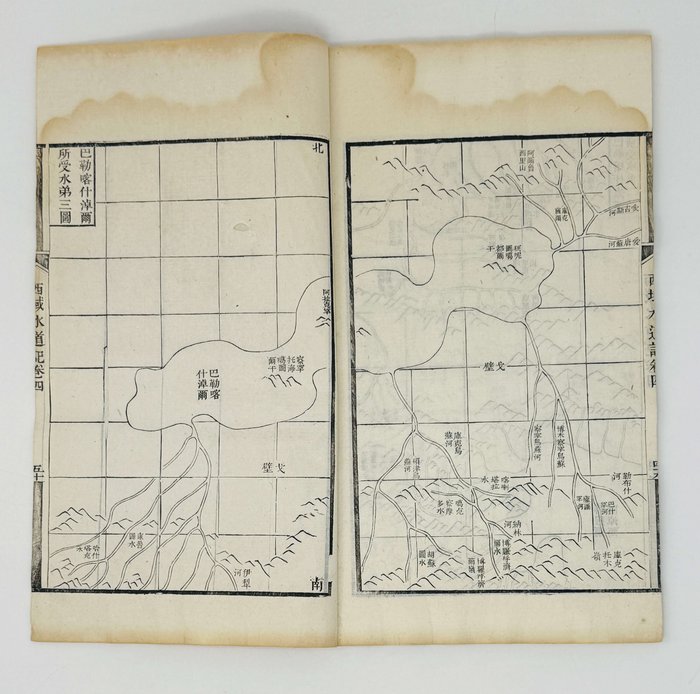

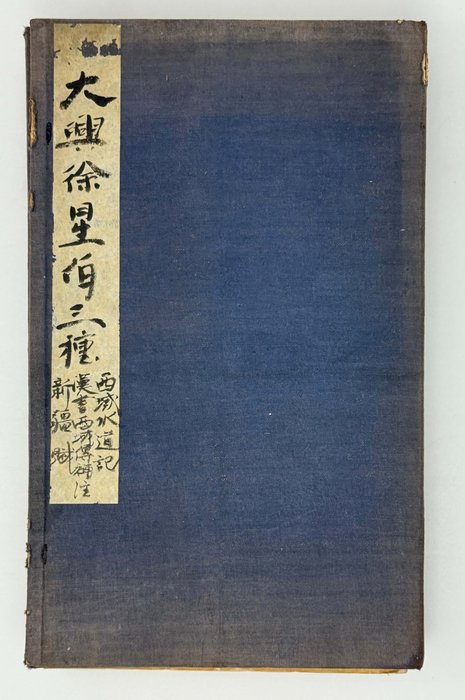

First edition. Complete set in 8 volumes. Large Quarto (ca. 29,5x27cm). Xiyu shuidao ji: 3, 5, 4, 30; 37; 46; 50; 44 leaves. Han shu Xi yu zhuan bu zhu: [1], 36, 34 leaves. Xinjiang fu: [1], 26 leaves. Woodblock printed edition with 24 two-page maps on separate leaves at the end of the volumes (eight in vol.2, five in vol.3, three in vol.4 and eight in vol.5 . Original fukuro toji bindings: light brown paper covers with leaves sewn together with thread. All housed in a 19th-century custom-made slipcase with an ink title on the front cover. Several ink stamps of a private library, occasional ink markings in text. Several leaves slightly waved, occasional water stains, one leaf of the second volume is damaged at the bottom; overall a very good set.

Very Rare Chinese imprint with only four paper copies found in Worldcat (Princeton University, Columbia University, University of Chicago, University of Washington).

An excellent example of a classic Chinese geographical treatise, written by the late Qing-period geographer and historian Xu Song. A native of Peking (Beijing), in the 1800s, he served in the Imperial Study and the Imperial Library, having compiled several works on Chinese history. “In 1811 he was accused by Chao Shen-chen (1762-1826), then a censor, of using his office to promote the sale of books which he himself had printed, and of not following the traditional practice of assigning topics for essays on the classics. He was dismissed and tried and in 1812 was sentenced to banishment to Sinkiang [Xinjiang], reaching his destination early in 1813. There he remained until 1820 when he was pardoned. During his exile he developed a keen interest in the history and geography of Sinkiang, and from his experience wrote three works on that region which appeared under the collective title Hsu Hsing-po hsien-sheng chu-shu san-chung. These works are: Hsin-chiang, 2 chuan, a long poem on Chinese Turkestan with detailed explanatory notes; Hsi-yu shui-tao chi, 5 chuan, an account of the river systems of Sinkiang; and Han-shu hsi-yu chuan pu-chu, 2 chuan, notes to the chapter of that region (Hsi-yu chuan) in the Han Dynastic History. These three works were printed in 1824, 1823, and 1829 respectively, and were later included in various collectanea.

At the initiative of Sung-yun, governor-general of Ili, Hsu Sung helped to bring to completion a work on the topography of Sinkiang, entitled Hsin-chiang chih-lueh. In order to acquire first-hand information about Sinkiang, Hsu was authorized by Sung-yun to travel (1815-16) through that region, and covered in this journey more than ten thousand li. After the Hsin-chiang chih-lueh was presented to the throne (1821) Hsu was awarded a position as secretary in the Grand Secretariat. Thereafter, for some twenty years, he held posts in various Boards and departments at the capital” (Hsu Sung// Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period (1644-1912)/ The Library of Congress, Ed. by Arthur W. Hummel. Vol. 1. A.-O. Washington, D.C., 1943, pp. 321-322; see more).

“The most important contribution of this book is a detailed critique of geographical statements about rivers found in ancient sources. [Xu Song] points at errors or distortions in names and places and makes clear that because of the climate some rivers just drain away. Xu works with a clear set of terms to describe the course of rivers and networks of waters. He explains how a river "leads to" (dao 導), "passes" (guo 過), "unites with" (he 合), "flows from" (cong 從), and "sheds its waters into" (zhu 注) a lake or else. Main currents (jingshui 經水, modern term zhuliu 主流) are "rising" (chu 出), "going through" (jing 逕), "converging" (hui 會), "coming from" (zi 自), and "entering" (ru 入). Confluences (zhishui 枝水, modern term zhilu 支流) are "arising" (fa 發), "passing" (jing 經), and "contributing" (hui 彙).

The famous "Water Classic" Shuijingzhu served as a model for the book, which describes river networks as arteria and sidelines. In Xu's concept, drainage basins are determined by lakes as terminal points of eleven river systems. Apart from the waters themselves, Xu provides information on roads, traffic, local products, cities, military garrisons, historic sites, mining sites, and population. Xu could draw from his rich travel experience during his exile in Xinjiang, and did not just rely on written sources, but also on his own view. He gives information on the history of the region, with a special focus on the Yuan 元 (1279-1368) and Qing periods, when Xinjiang was conquered from the east.

The text is enriched by 24 maps showing drainage basins. In case river names are derived from Mongolian, Xu provides a translation into Chinese or gives information on names in Turki or even Tibetan” (Xiyu shuidao ji/ ChinaKnowledge.de – An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History and Literature; see more).

In the section “Water Received by Zaisang Nur”, the historical and geographical features of Russia, described as the "big country in the north," are presented in great detail.

“In 1759 the Qianlong Emperor brought to a successful conclusion the northwestern campaigns initiated by his illustrious grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor. As a result, the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) annexed vast territories on China’s Central Asian frontier and enormously enlarged the empire, dispelling forever the threat of nomadic invasion that had haunted its predecessors for more than fifteen hundred years. Even before the region had been completely pacified, the Qing began to explore the possibility of despatching political and criminal exiles to Xinjiang, the “new territories.” <…>

Xinjiang lies more than three thousand miles northwest of Beijing on the old Silk Road that connected China to Western Asia and Europe. Separated from China proper by the Gobi Desert, it has been subject to degrees of Chinese political control at intervals for two millennia, but its heterogeneous and largely Muslim population has resisted assimilation into the Chinese cultural world. Initially governed as a military protectorate, Xinjiang was, for eighteenth-century Chinese, a largely alien land, known mainly to scholars through accounts of the ‘‘Western Regions” (Xiyu) found in centuries-old dynastic histories and through the occasional reports of travelers, merchants, and soldiers. Shortly after the conquest of Xinjiang, the Qing began employing banished government officials for little or no remuneration in the lower echelons of the frontier administration. The effects of this policy were far-reaching. By exploiting these exiles’ administrative experience, the Qing avoided having to match the dramatic territorial expansion of the empire with a corresponding increase in personnel expenditures. At the same time, for many exiles, including the influential geographer, poet, and population theorist Hong Liangji (1746-1809) and the well-known historians Qi Yunshi (1751-1815) and Xu Song (1781-1848), first hand knowledge of the region brought a fascination that found expression in their scholarly work, which had a wide circulation. After their return, they fuelled a growing interest in frontier studies that laid the intellectual groundwork for granting Xinjiang provincial status in 1884, a move that confirmed the region’s ultimate political integration into the Chinese state” (Introduction/ Waley-Cohen, J. Exile in Mid-Quing China: Banishment to Xinjiang, 1758-1820. Yale University Press, 1991, p. 1).