#OA10

1876

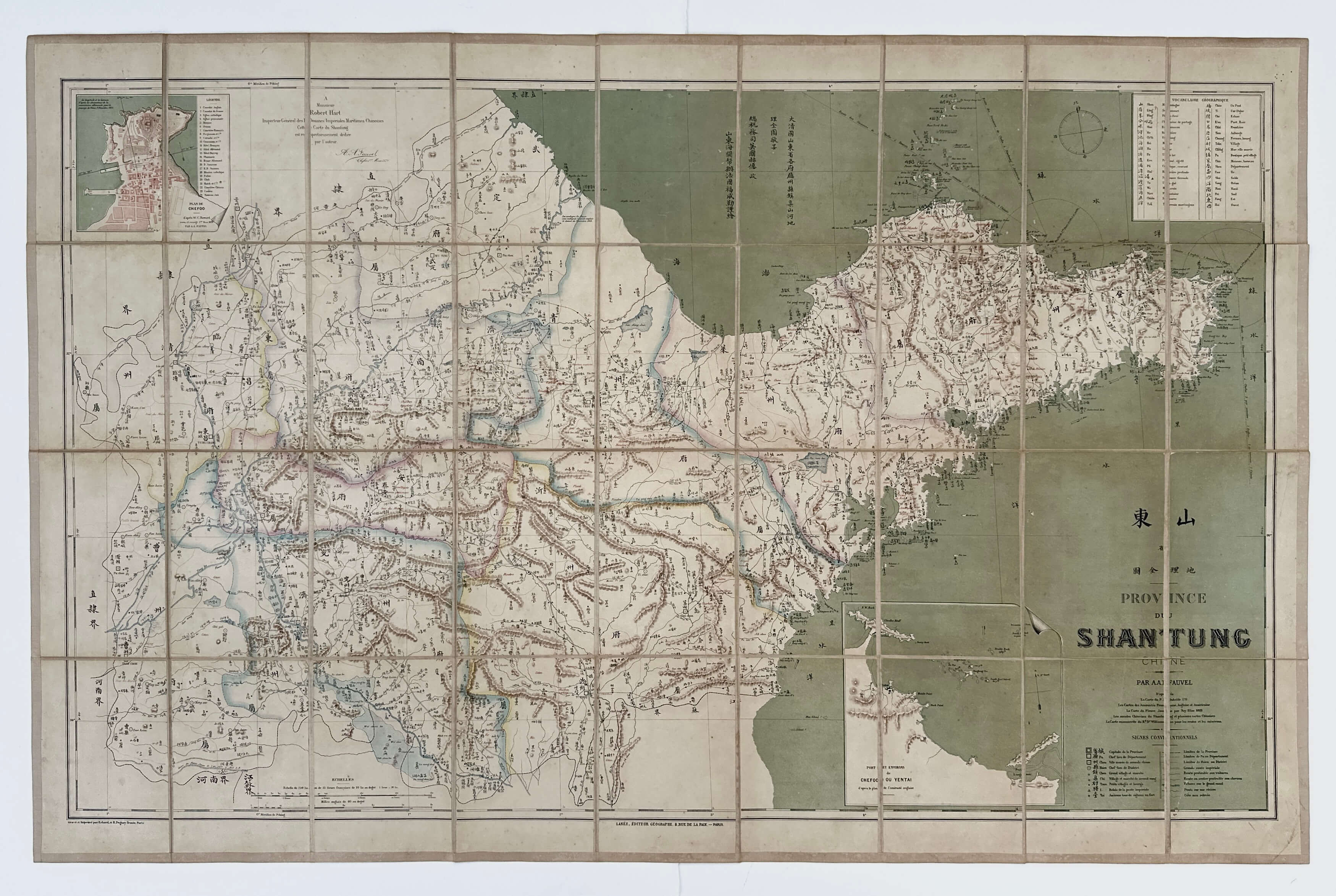

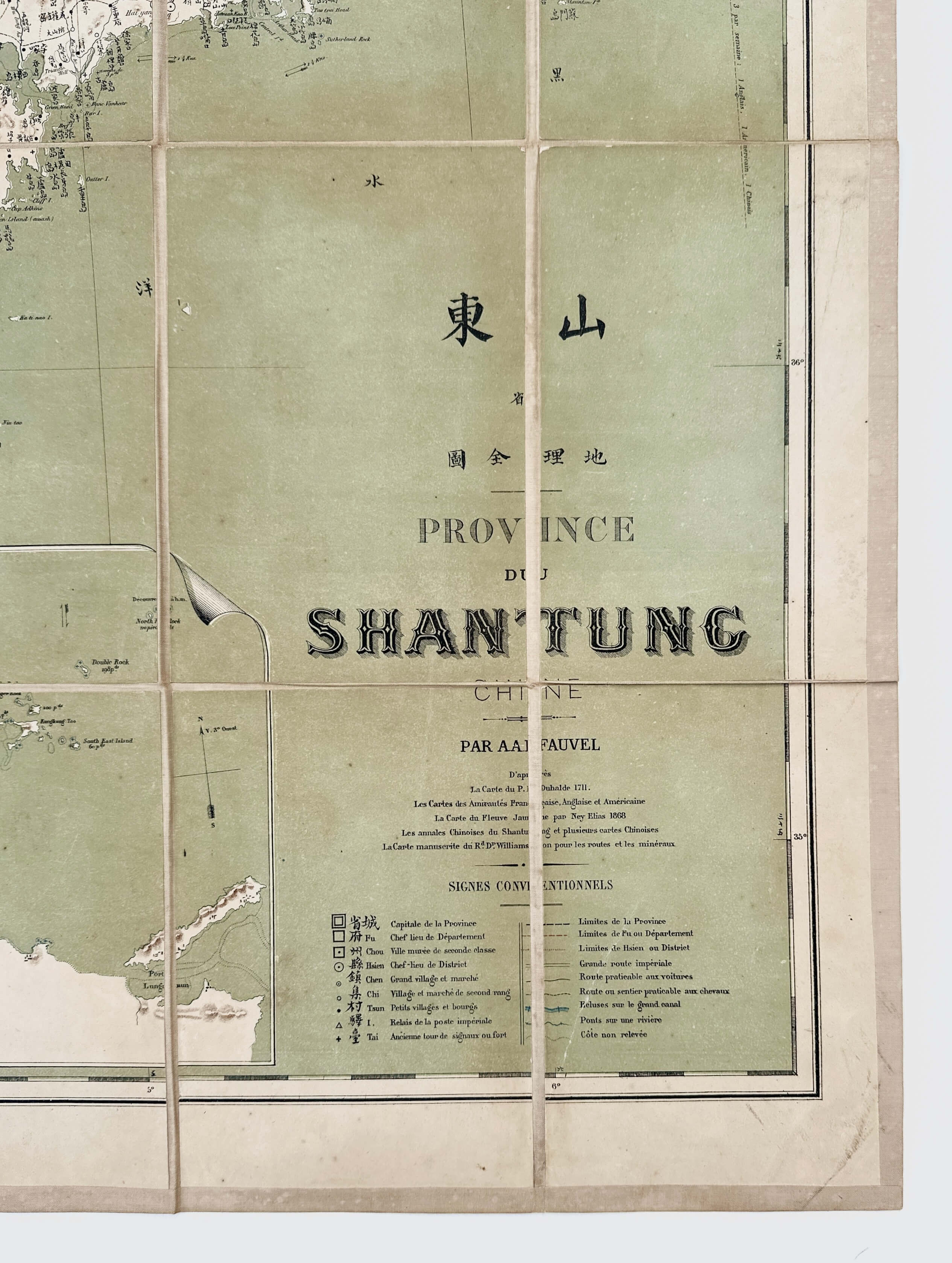

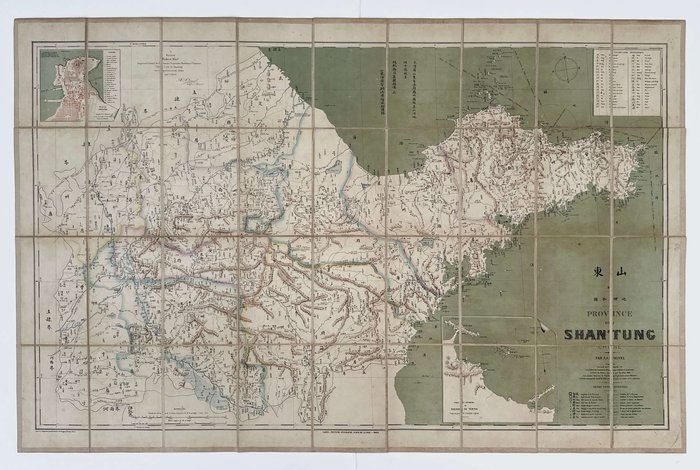

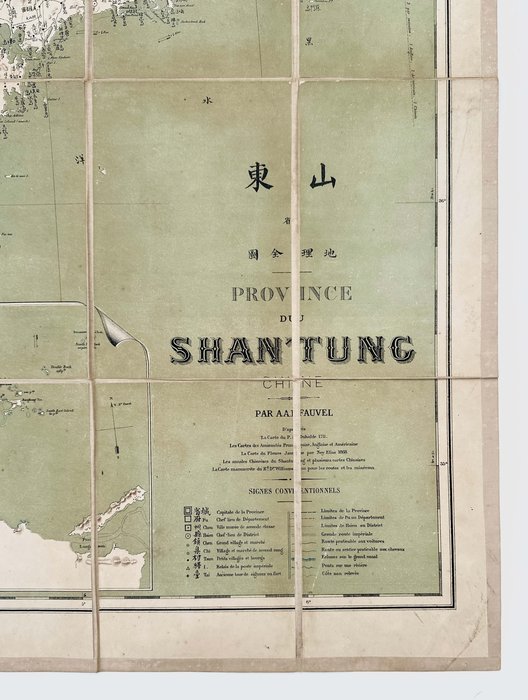

Large folding lithographed map ca. 70x110 cm (27 ½ x 43 ½ in), dissected into 36 compartments and linen backed. Borders outlined in colour. With two inserts. The title and legend in the right lower corner, concise Chinese-French vocabulary of geographical terms in the right upper corner; names of the publisher and typographer on the lower margin. Place names in parallel French and Mandarin. Paper label of a Paris bookstore of Eugène Andriveau-Goujon pasted on verso. Map slightly age-toned, the linen of the outer compartments slightly soiled on verso, but overall a very good map.

Very rare imprint with only three paper copies found in Worldcat (Harvard University, National Library of Australia, Sorbonne University).

Rare first edition of the early detailed French map of the eastern Chinese province of Shantung (Shandong), compiled just over a decade after China had opened its ports to foreign trade as a result of its defeat in the Second Opium War (1856-1860). The compiler was a French naturalist and explorer, Albert-August Fauvel, who in 1872-1884 served in the Chinese Imperial Customs Service in Chefoo (Yantai) – the seat of the region’s foreign commerce. During the Sino-French War (1884-1885), Fauvel quit the Imperial Customs service and transferred to the Messageries Maritimes company, travelling around the Far East (Singapore, Dutch East Indies), Seychelles and Brazil. He compiled several works on the natural history and geography of Shandong Province and China and published the first detailed description of the Chinese alligator (Fauvel, A.A. Alligators in China: Their History, Description & Identification/ North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Shanghai, 1879).

The map, dedicated to Fauvel’s superior, Sir Robert Hart (1835-1911), the second inspector-general of Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service (1863-1911), roughly covers the territory of modern-day Shandong Province, partly enclosed in the north, west and south by the main body and tributaries of the Yellow River, the constituent lakes of the Nansi Lake system and the Grand Canal of China. Compiled with great attention to details, the map marks the region’s mountain ranges and peaks (including Mount Tai, the most revered peak of Taoism; heights are also indicated), rivers and lakes (including the old course of the Yellow River in the south of the province, which drastically reversed after disastrous floods of 1851-1855), the capital (marked as “Chi Nan Fu”) and settlements from major cities to villages and forts (additionally identifying their administrative grades); roads (passable by wagon and on horseback), bridges, locks of the Grand Canal, prefecture borders, and natural resources (“charbon,” “cristal de roche,” “amethyste,” “argent,” “galena,” “fer,” &c.).

Puncture lines connecting in the port of Chefoo (Yantai) in the north of the Shandong Peninsula (opened for foreign trade in 1861) indicate steamer routes to Tientsin (Tianjin), Niuchuang (Yingkou) and Shanghai. The map also marks the villages of We-ha-wei (future British leased territory, 1898-1930) on the northern coast and Ching-Tao (future German colony of Tsingtao, 1898-1914), which controlled the entrance to “Chiaochou” Bay on the southeastern coast of the province.

Very interesting is that this is one of the early examples of a bilingual map of China, with geographical names initially outlined in Mandarin and transliterated into French. The compass on the top right uses Chinese characters instead of traditional Latin letters; degrees of latitude and longitude on the margins are written in Arabic numerals and Chinese characters. The map uses Peking (Beijing) as the prime meridian, rather than Paris or Greenwich, which indicates it was intended mostly for the audience in China and the Far East. Two inserts include a plan of Chefoo (mostly the European settlement, marking English and French consulates, Catholic and Protestant churches, offices of commercial companies, hotels, clubs, French and Chinese cemeteries, a pharmacy, “Bazar Allemand,” &c.) and a map of the coast around the port of Chefoo and the Chinese village of “Yentai.” A concise geographical vocabulary in the upper right corner provides one of the early translations of Chinese concepts of space into the most relevant French terms.

Overall an important early map of the Shandong Peninsula, illustrating the depth of European knowledge of the region just over a decade after its opening to foreign trade, but before the takeover of Weihaiwei and Tsingtao (Qingdao) by Britain and Germany in the late 1890s.