#M66

1881

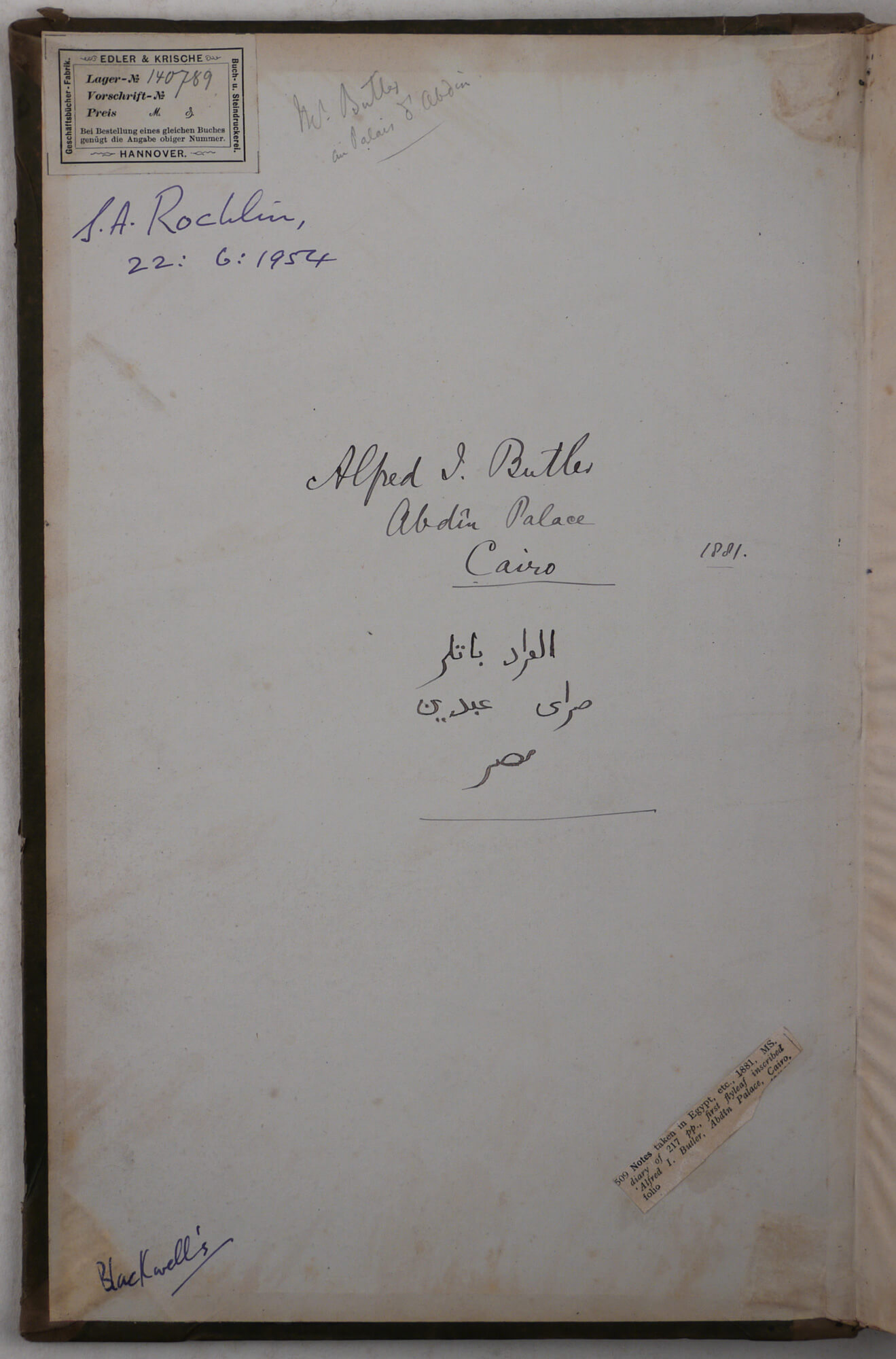

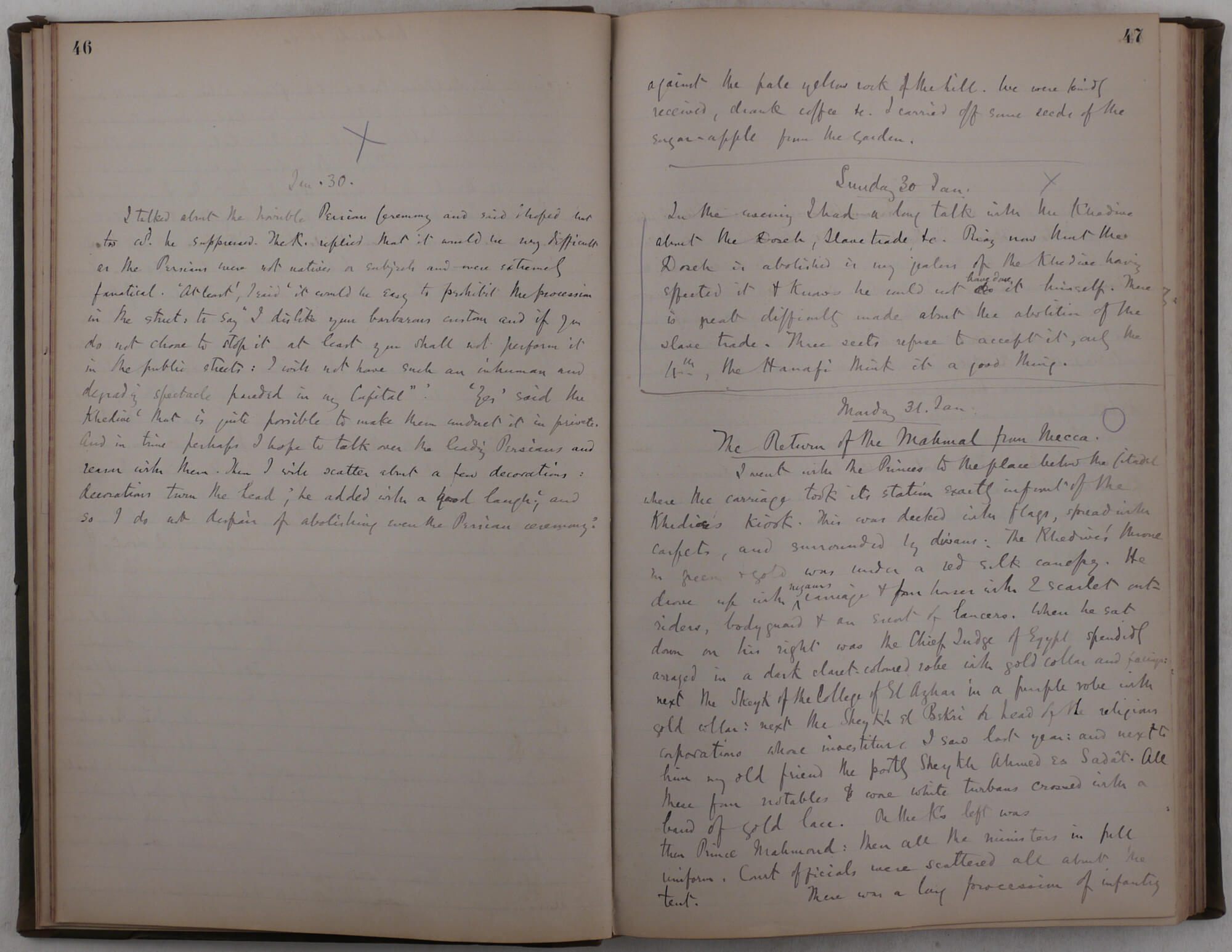

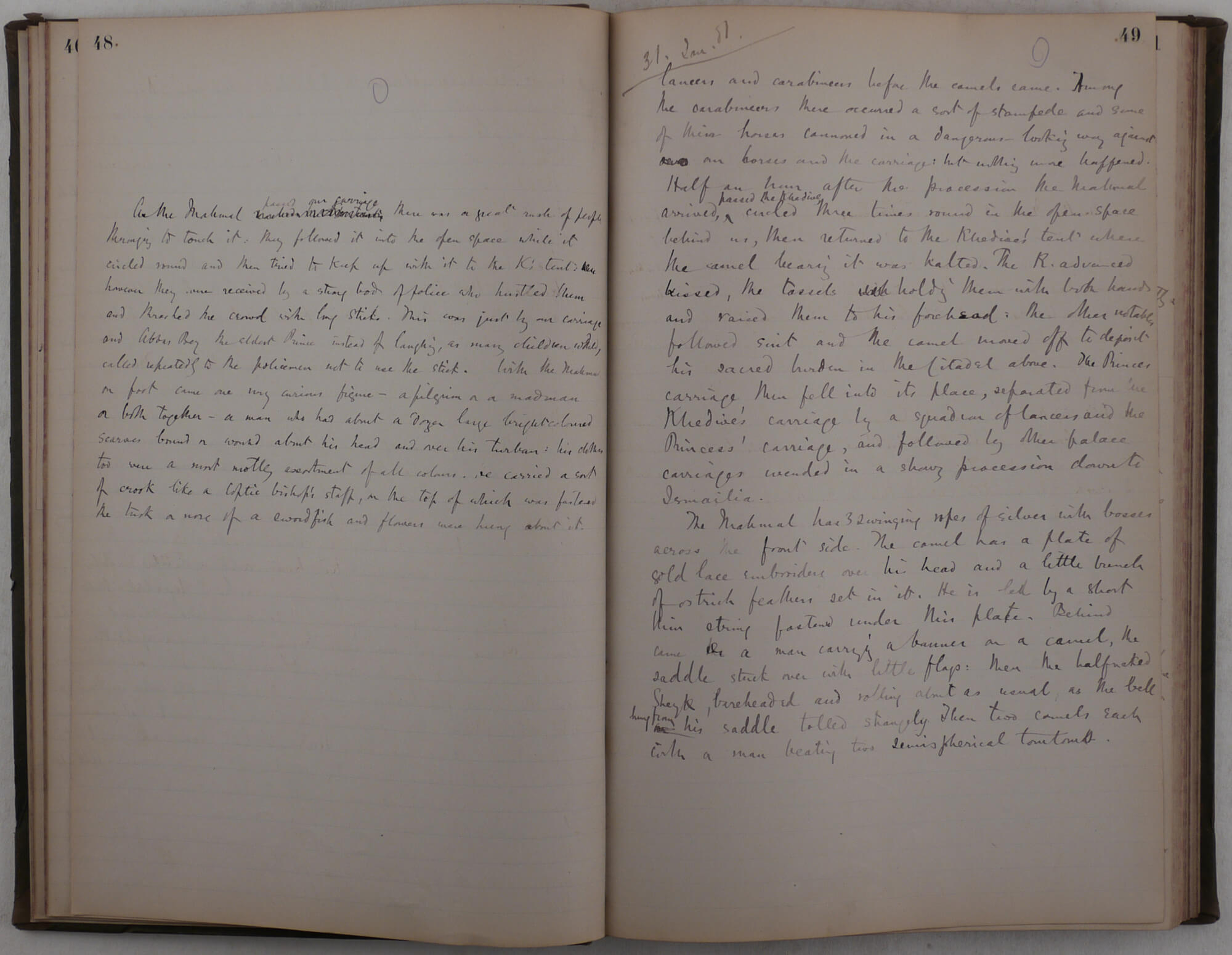

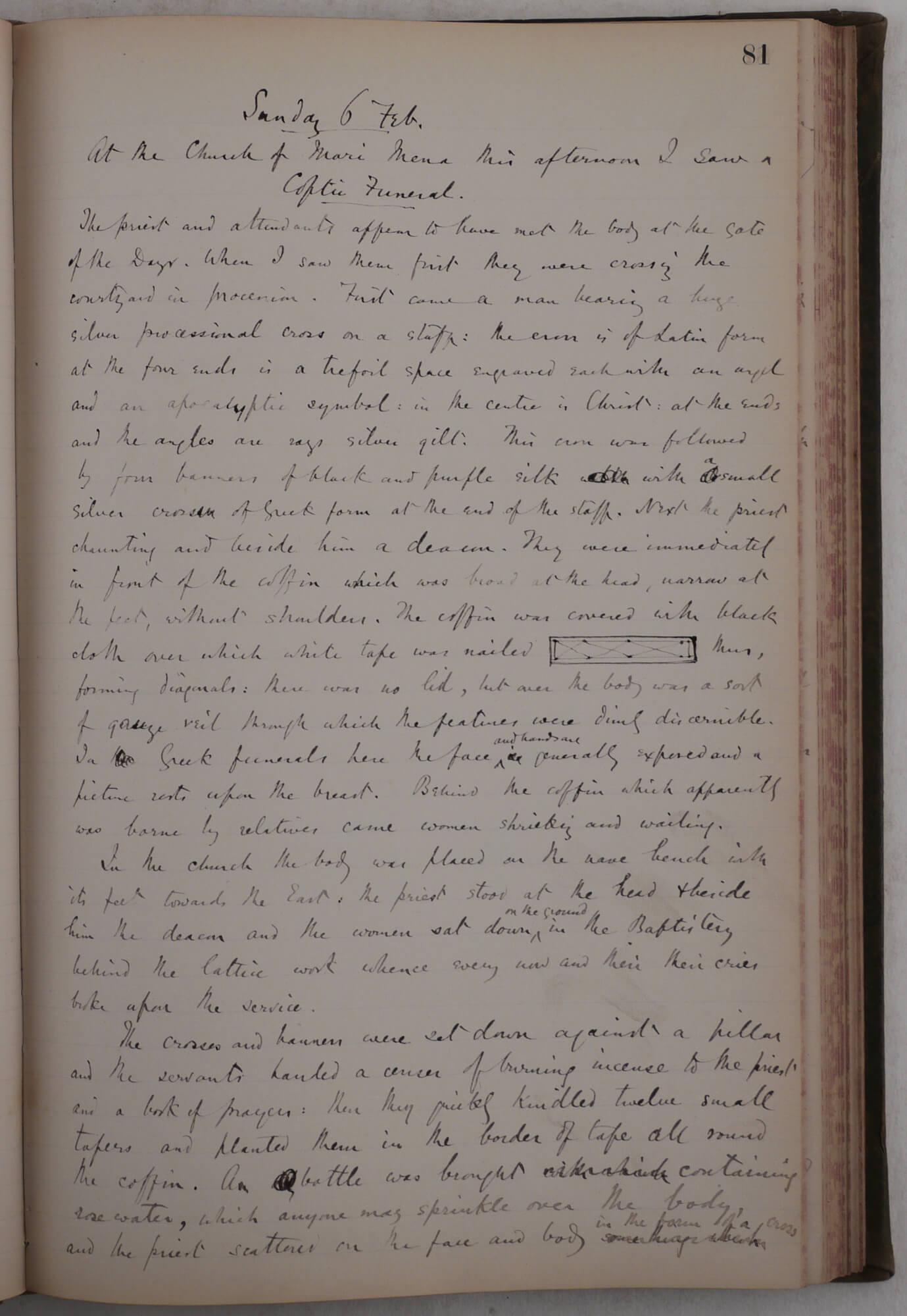

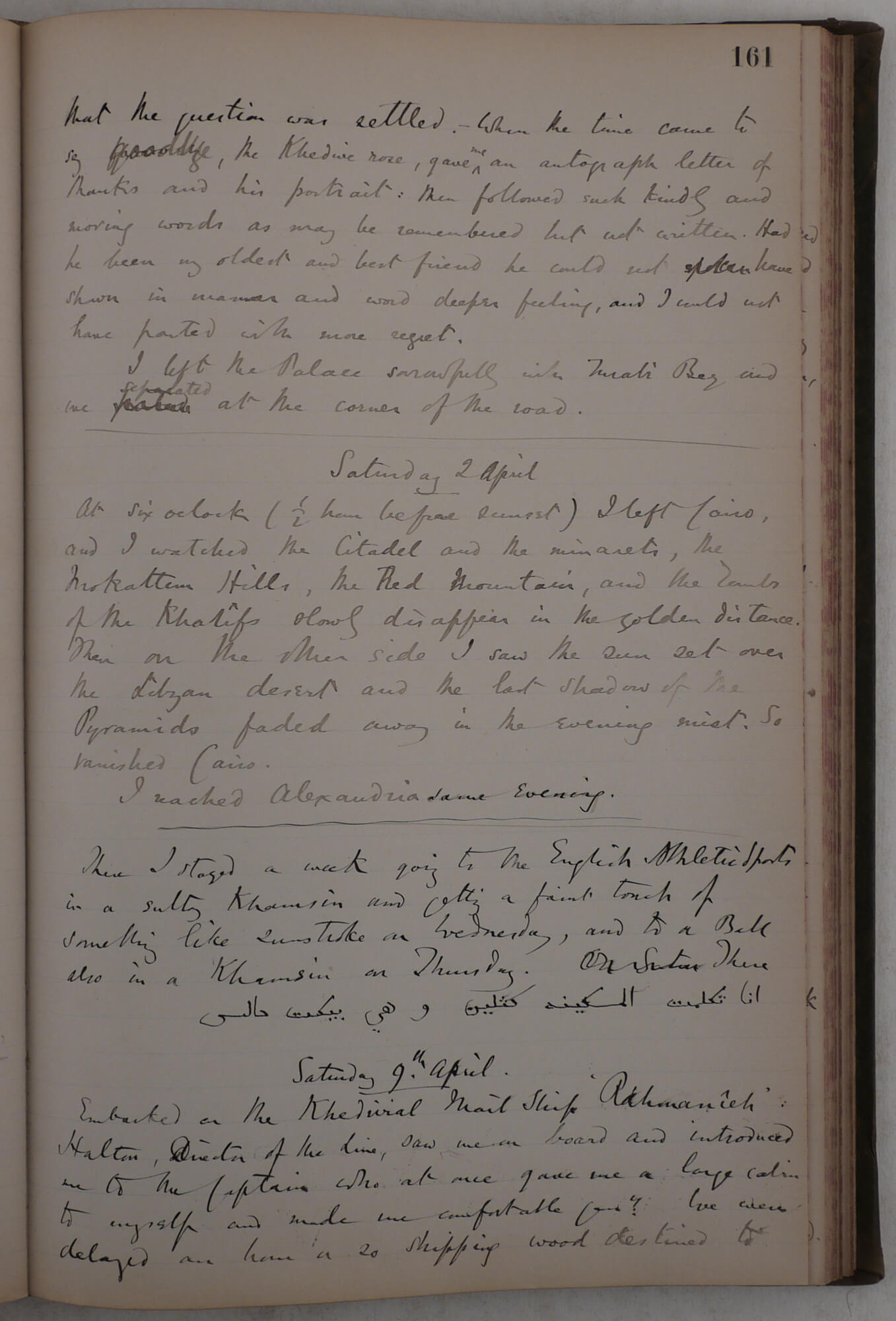

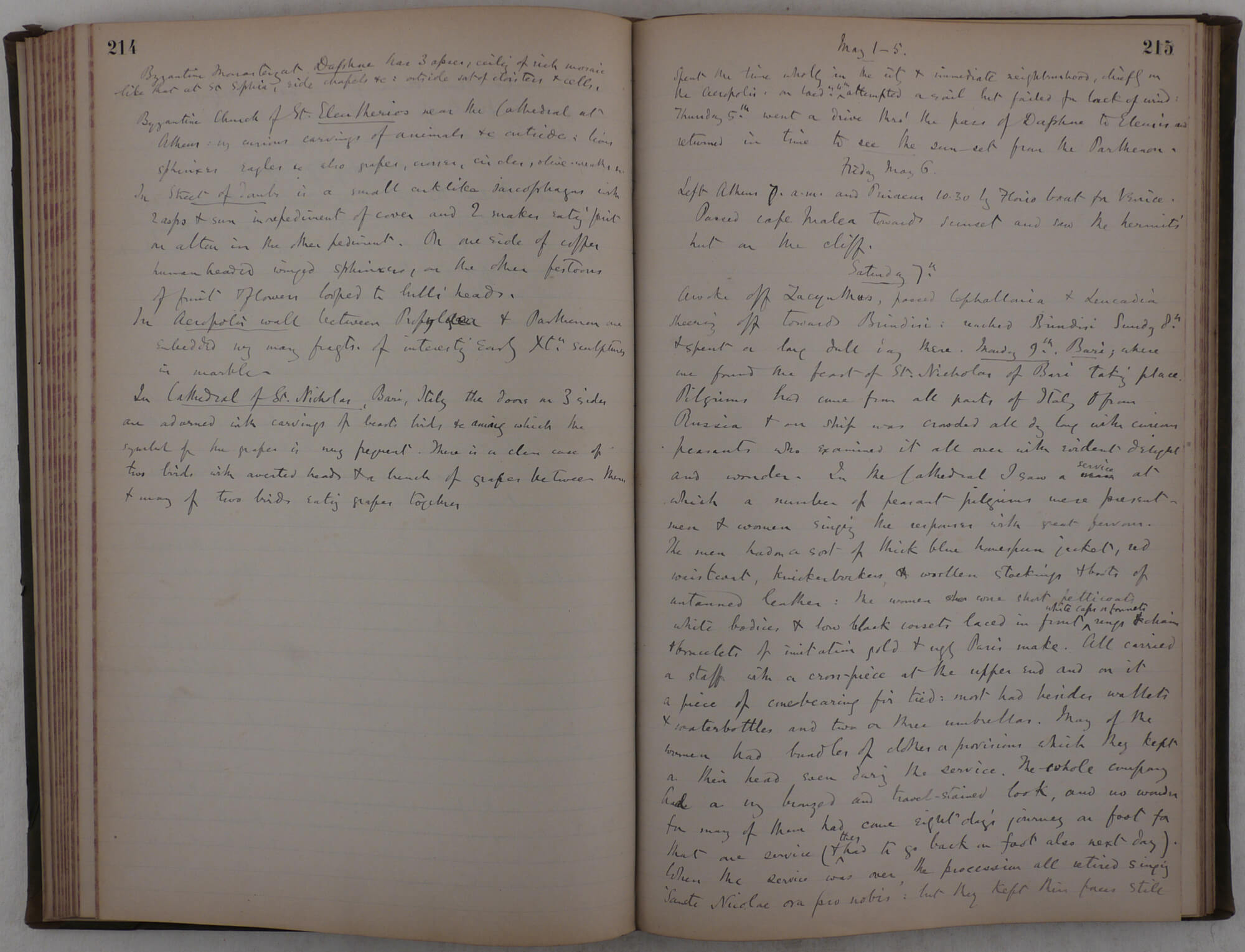

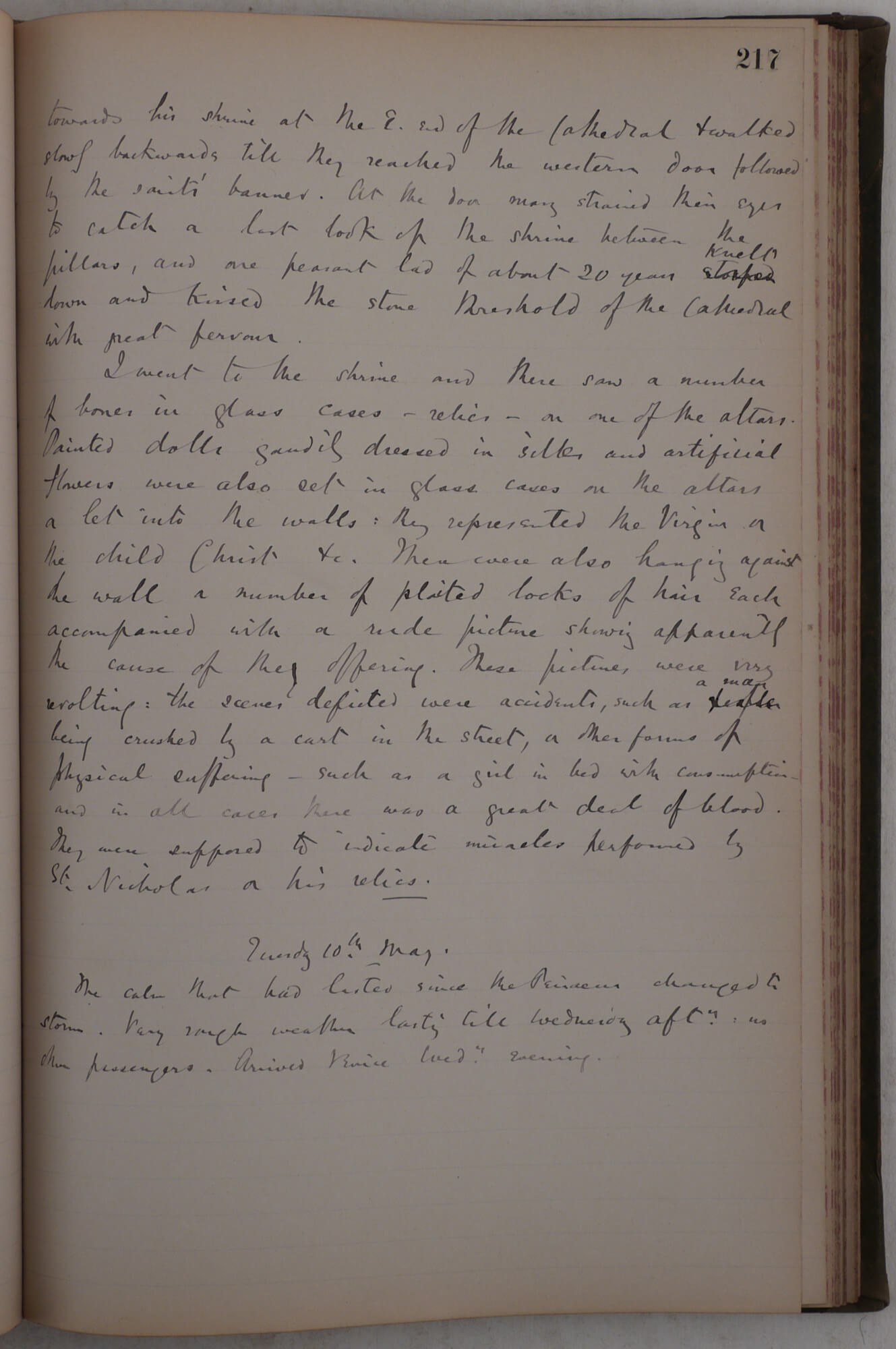

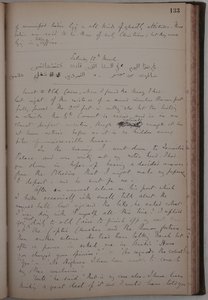

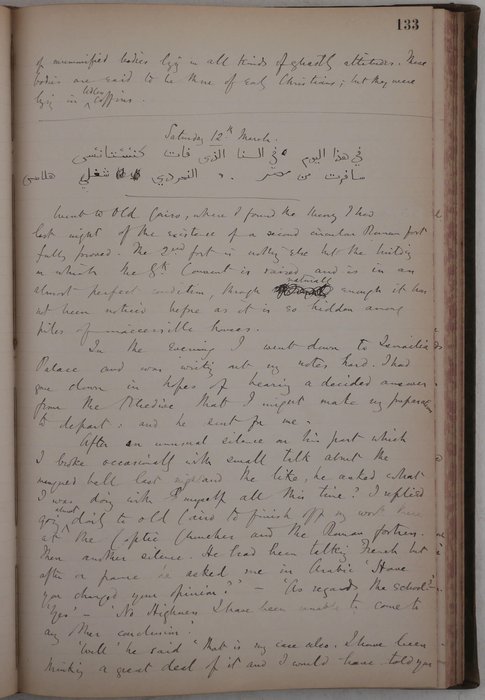

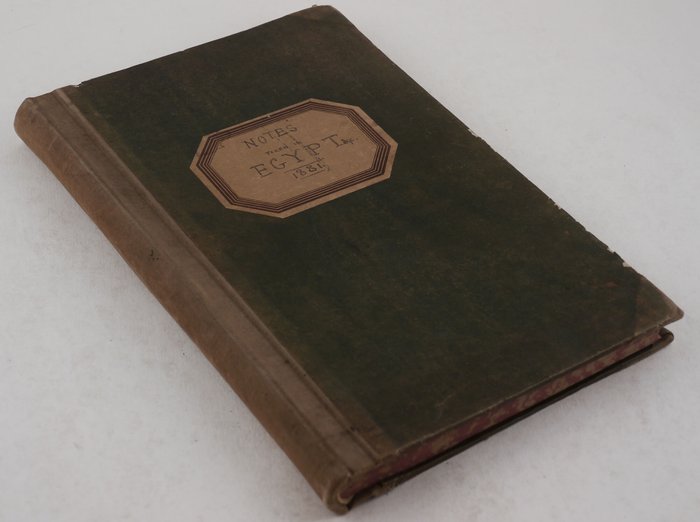

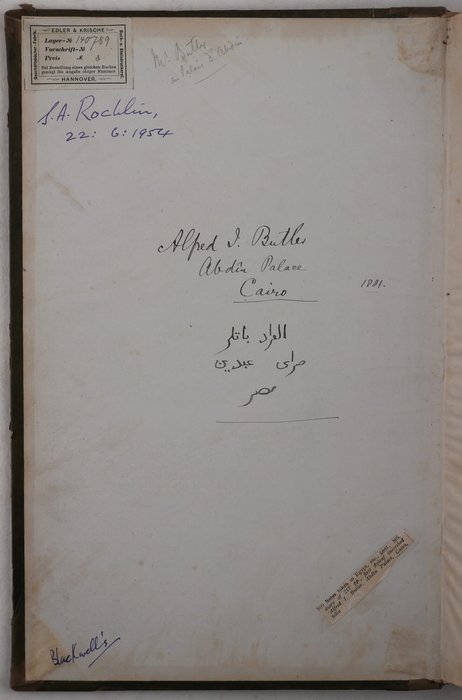

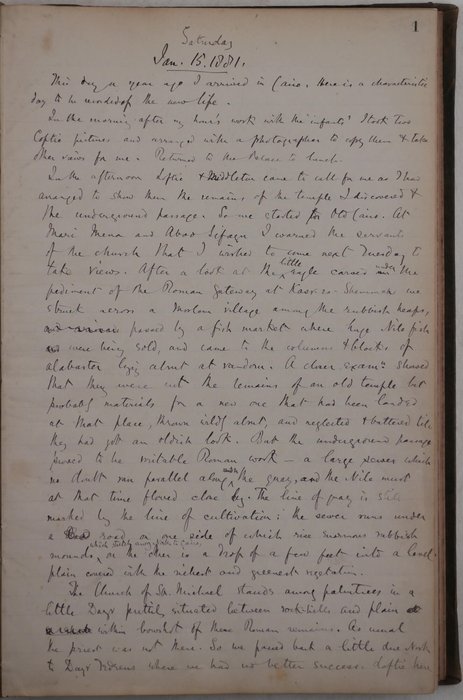

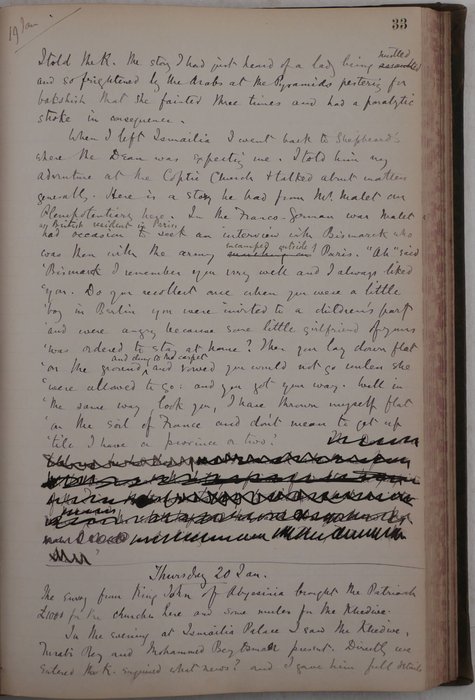

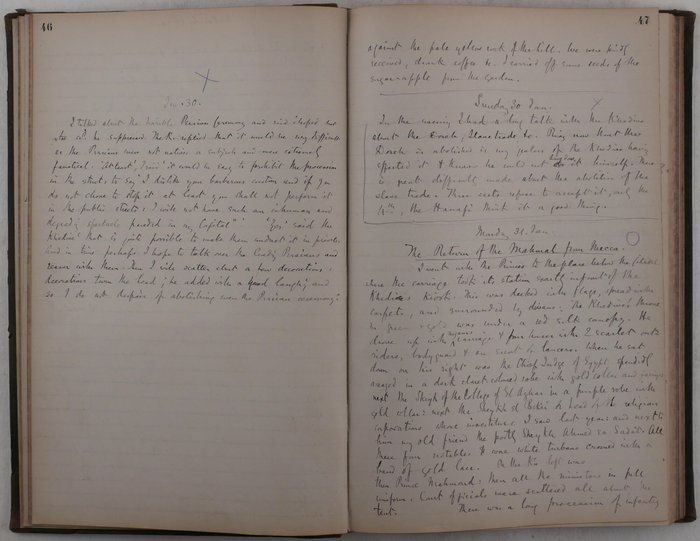

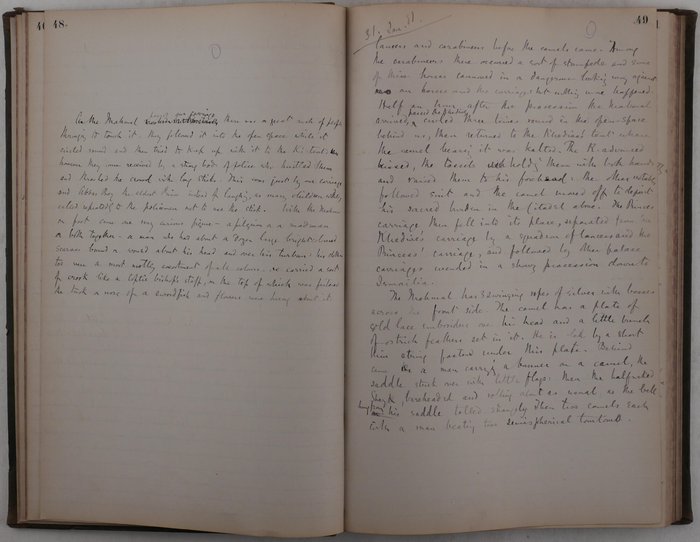

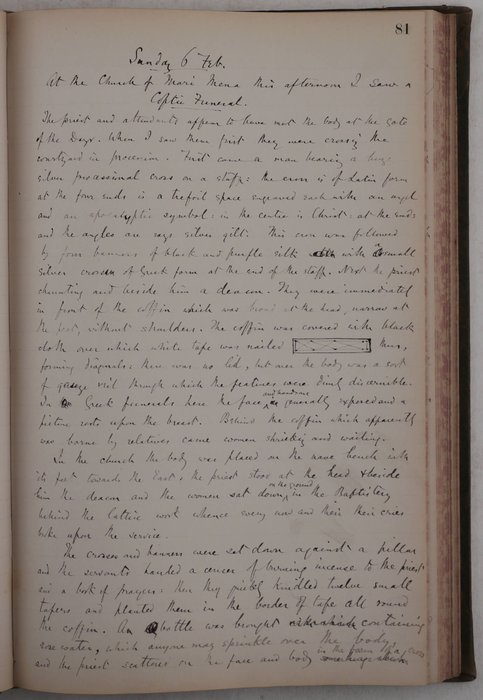

Folio journal (ca. 36x23 cm). 376 numbered pages, of which 217 are filled in manuscript ink, mostly on rectos (with additional shorter or longer passages of text on versos of seven leaves), which constitutes about 110 pages of text. Black and brown ink on lined paper, occasional author’s corrections and markings in text. Front pastedown endpaper with the author’s ink inscription in English and Arabic “Alfred J. Butler, Abdîn Palace, Cairo, 1881,” an ink inscription of S.A. Rochlin (South African politician and Islamicist), dated 22 June 1954; and a clipping from a 20th-century bookseller’s catalogue describing the journal. Original hardcover with the canvas spine and papered boards, paper label with a manuscript title on the front board, binder’s paper label on the front pastedown endpaper. Lower and upper halves of leaves 25-26 and 27-28 are removed, together with the text of the entry for 17 January 1881, otherwise a very good journal written in a legible hand.

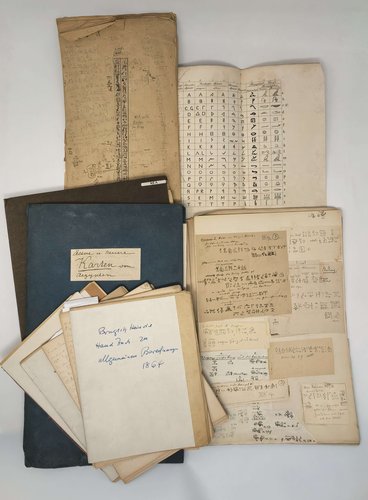

Historically significant extensive diary authored by a prominent British historian and Coptic scholar Alfred Joshua Butler. He graduated from Oxford in 1874, became a fellow of the Brasenose College in 1877, and received a doctorate in 1902. In January 1880 – April 1881, Butler served as a tutor to the sons of Tewfik Pasha (1852-1892), the Khedive of Egypt & Sudan (1879-1892). While living in Egypt (in 1880-1881 and during a separate trip to the monasteries in Wadi El Natrun near the Nile Delta in winter 1883-84), Butler thoroughly studied and photographed Coptic churches and monasteries and actively communicated with Coptic clergy, including Pope Cyril V (Abba Kyrillos V, served as Pope in 1874-1927). Butler authored several fundamental works on Coptic history, including “The Ancient Coptic Churches of Egypt” (Oxford, 1884, in 2 vols.), “The Arab Conquest of Egypt and the Last Thirty Years of the Roman Dominion” (Oxford, 1902), “Babylon of Egypt: A Study in the History of Old Cairo” (Oxford, 1914), and others.

The diary covers the period of January 15 – May 10, 1881, and provides rich insider information about Egyptian internal policy and relations between the Khedive, the Egyptian elite and European diplomats and residents in Cairo. Highly educated and well-versed, Butler provides a truly captivating account, in which court politics, rumours, sketches of Egyptian daily life and expert notes on Coptic architecture and history combine in a story that powerfully draws the reader in. Many details which Butler reveals, were not included in his book “Court Life in Egypt” (London, 1887), which described the same period of his life (January 1880 – April 1881).

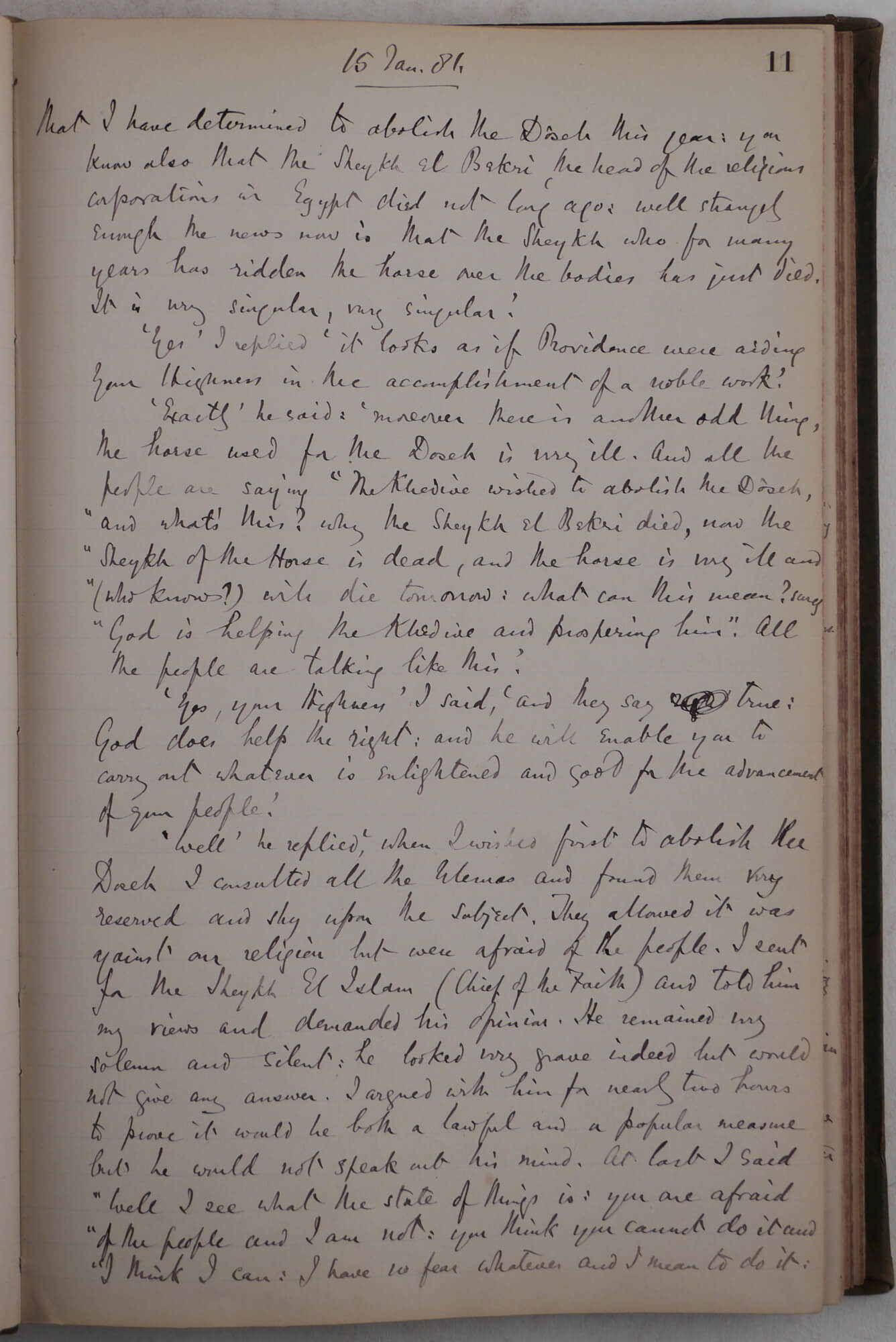

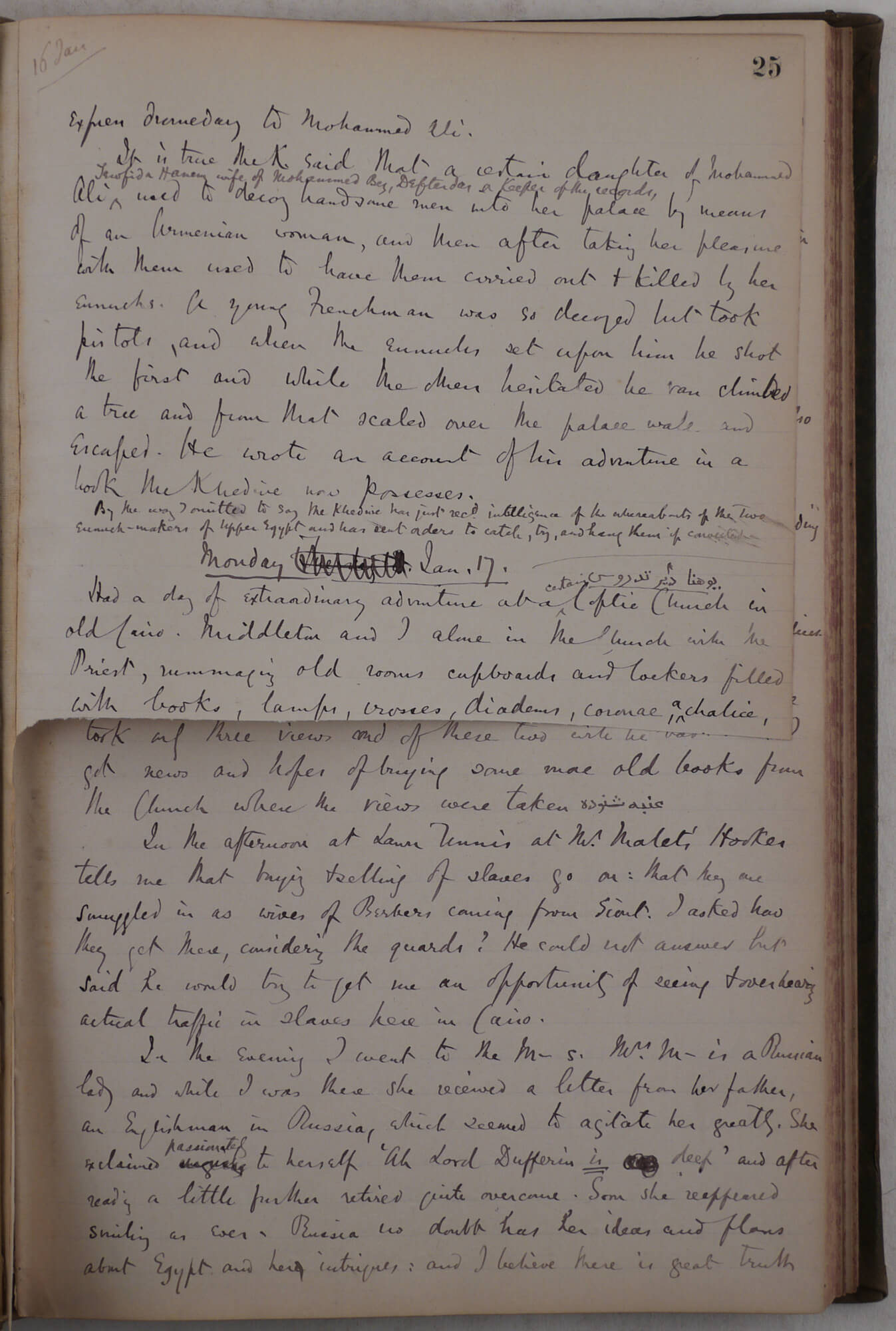

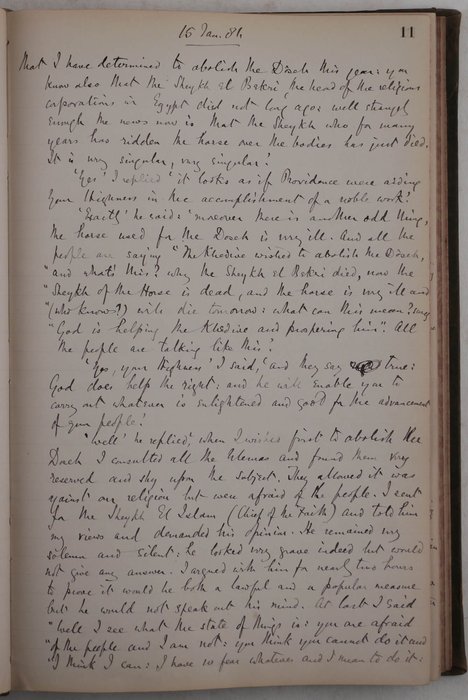

Butler extensively talks about his audiences and conversations with the Khedive. For example, an eight-leaves long description of their four-hour conversation (pp. 6-23) discusses Egypt’s relations with “King John” (Yohannes IV of Ethiopia), “Colonel Gordon” (Charles George Gordon, Governor-General of Sudan in 1877-79 and 1884-85), Khedive’s decision to abolish the rite of “Dosah” during the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday (when the sheikh of the Dosah rode his horse over a line of prostrated dervishes), and the Khedive’s idea of the entire abolition of slavery in Egypt. Butler frequently mentions or describes his interactions with many influential Egyptian figures - “Riaz Pasha” (Riyad Pasha, served as Egyptian Prime Minister three times, including in 1879-81), “Mustapha Pasha” (Mostafa Fahmy Pasha, Egyptian politician, Prime Minister of Egypt in 1891-93), “Turabi Bey” (English secretary to the Khedive), Mr. Malet (Sir Edward Malet, British Consul-General in Egypt in 1879-83), Coptic Pope Cyril V, Rev. Greville John Chester (notes poet, clergyman and collector of Egyptian antiquities), Sir Frederic J. Goldsmid (British military officer active in the Middle East), and many others.

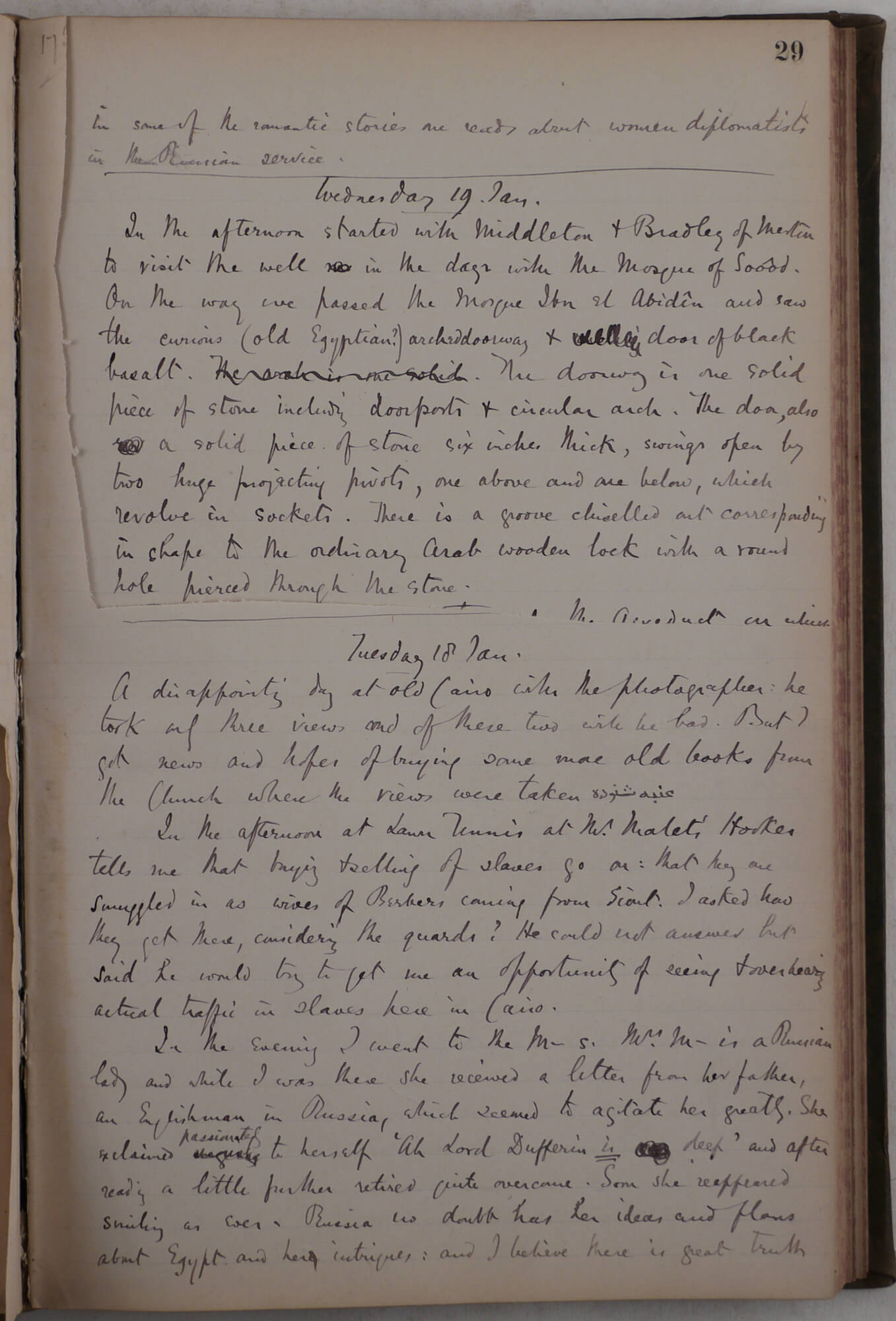

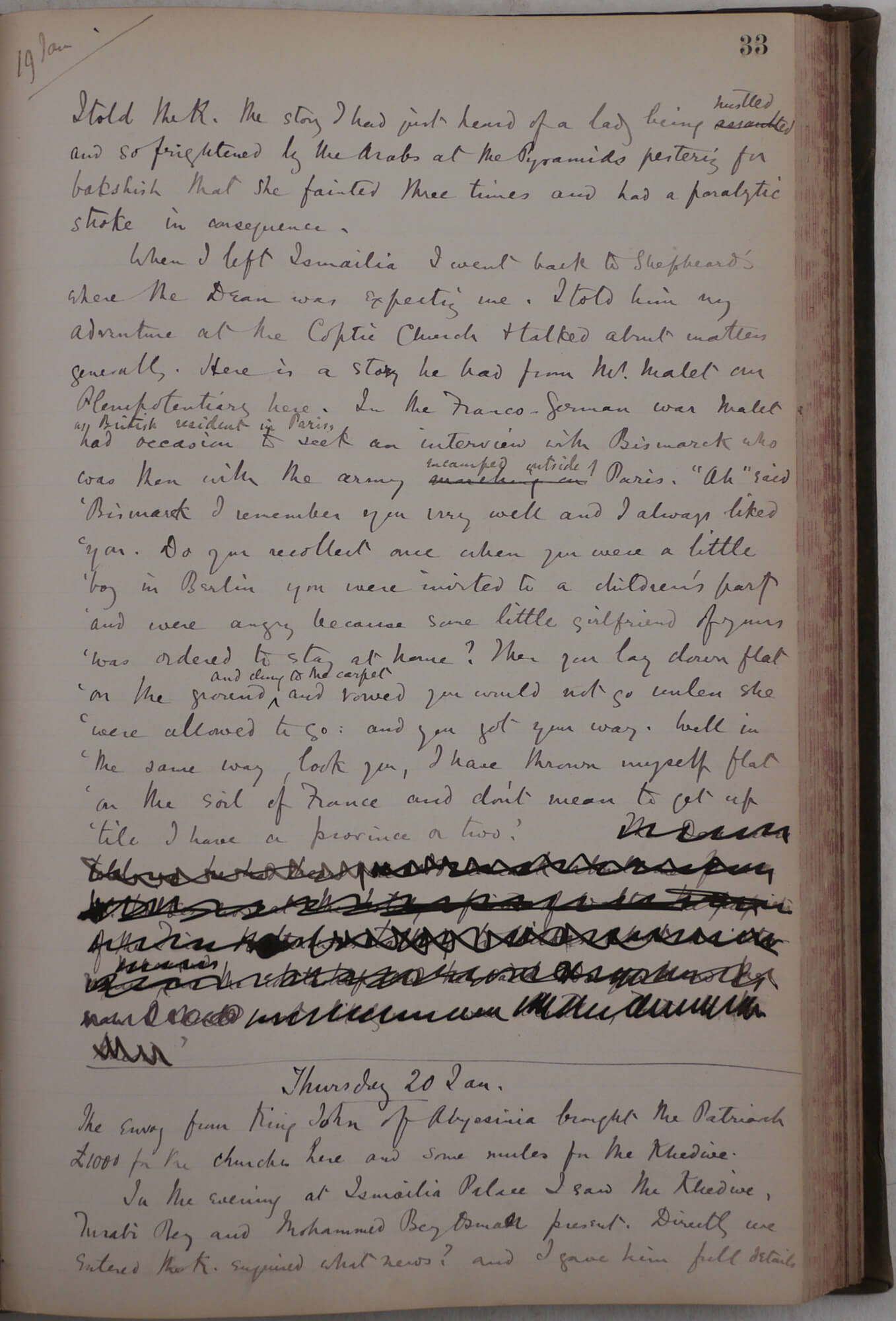

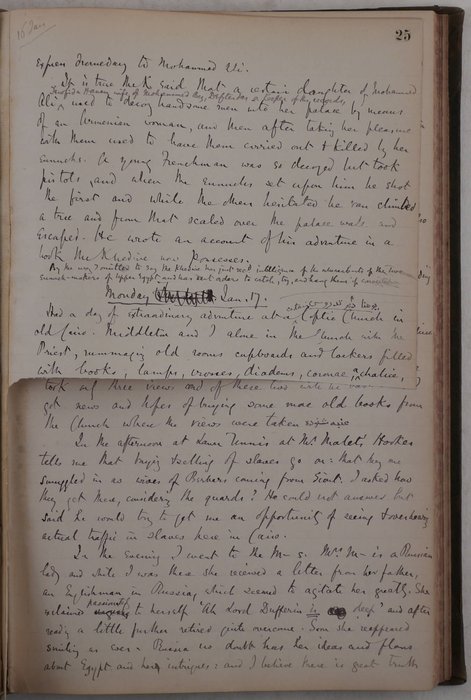

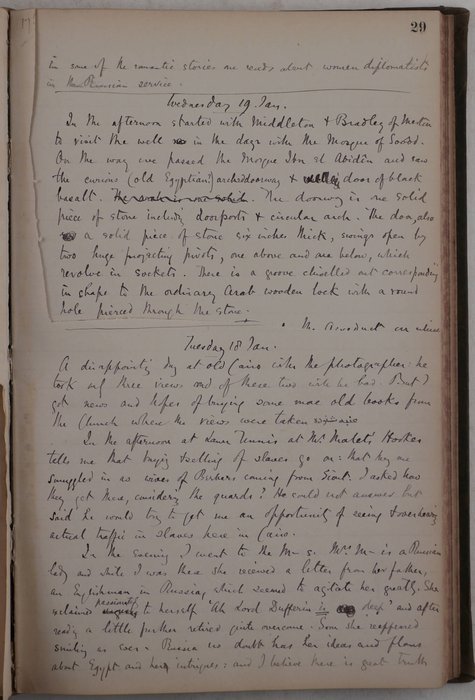

Among the topics discussed: rivalry between the English and the French for the control over the Egyptian Museum (p. 23), Russian intrigues at the Egyptian court (Jan. 18), conversations between Edward Malet and Otto von Bismarck (Jan. 19), Butler taking photos of Coptic churches and antiquities (Jan. 15), welcoming ceremony of Mohmal and pilgrims returning from Mecca (Jan. 31), the “mutiny of three colonels” (Feb. 1), the wedding of the Khedive’s sister princess Jemileh Hanem (Feb. 2 and 3), the case of “Sheikh Towara from Mount Sinai” who had to pay “at the bridge of the Suez Canal 4 piastres toll for every camel” (Feb. 4), a ceremony of Coptic funeral (Feb. 6), celebrations of Prophet Mohammad’s birthday (Feb. 7), the Russian government and its fight with the terrorists (Feb. 8), Khedive’s audience to the uncle of the Shah of Persia (Feb. 17), late dinner on the Great Pyramid (Mar. 15), Egyptian slavery laws (Mar. 29), and many others.

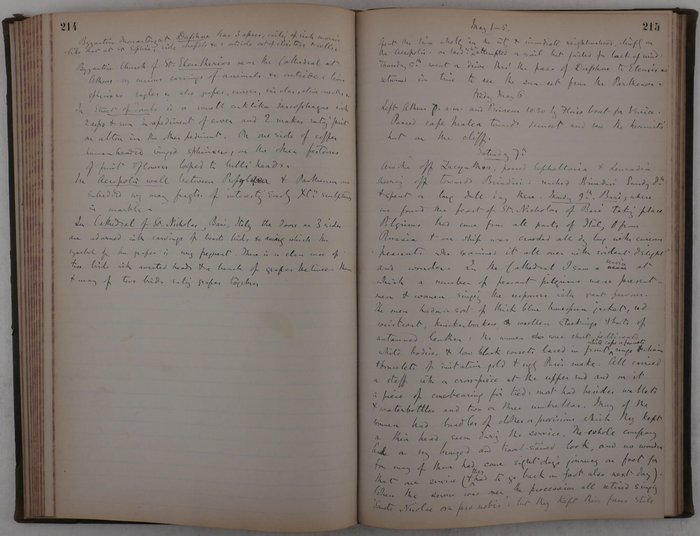

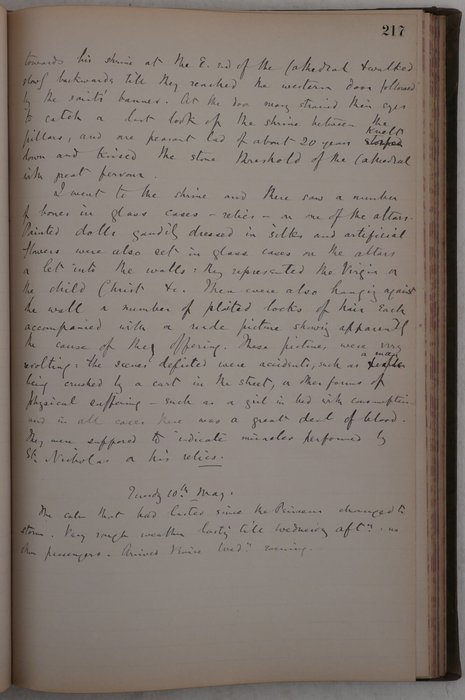

The entries from April 2 to May 10, 1881 (pp. 161-217) describe his return journey to Europe on board the Khedive Mail Steamship Co.’s steamer “El Rahmanieh.” Butler stopped at several Greek islands, Smyrna (Izmir), Constantinople (Istanbul), and Athens; the diary ends with his arrival to Venice. This part of the diary contains interesting notes on the volcanic activity on Santorini Island (Apr. 9), stories about the recent earthquake on Chios Island (Apr. 12) and an eye-witness account of the destruction of the city of Chios (Apr. 14), an account of a massive hunt for locusts in Smyrna on the Turkish governor’s order, (Apr. 15), excursions to Istanbul and along the Golden Horn (Apr. 17-20), description of a high-class Turkish passenger (Apr. 20), an account of a train trip from Smyrna to the ruins of Ephesus (Apr. 23), and a thrilling story of Butler’s interactions with Turkish “brigand looking men” in the mountains near Sardis, who took him for an Arab and tried to take his watch (Apr. 25).

Overall an invaluable original source on the history of Egyptian life and politics in the latter part of the 19th century.

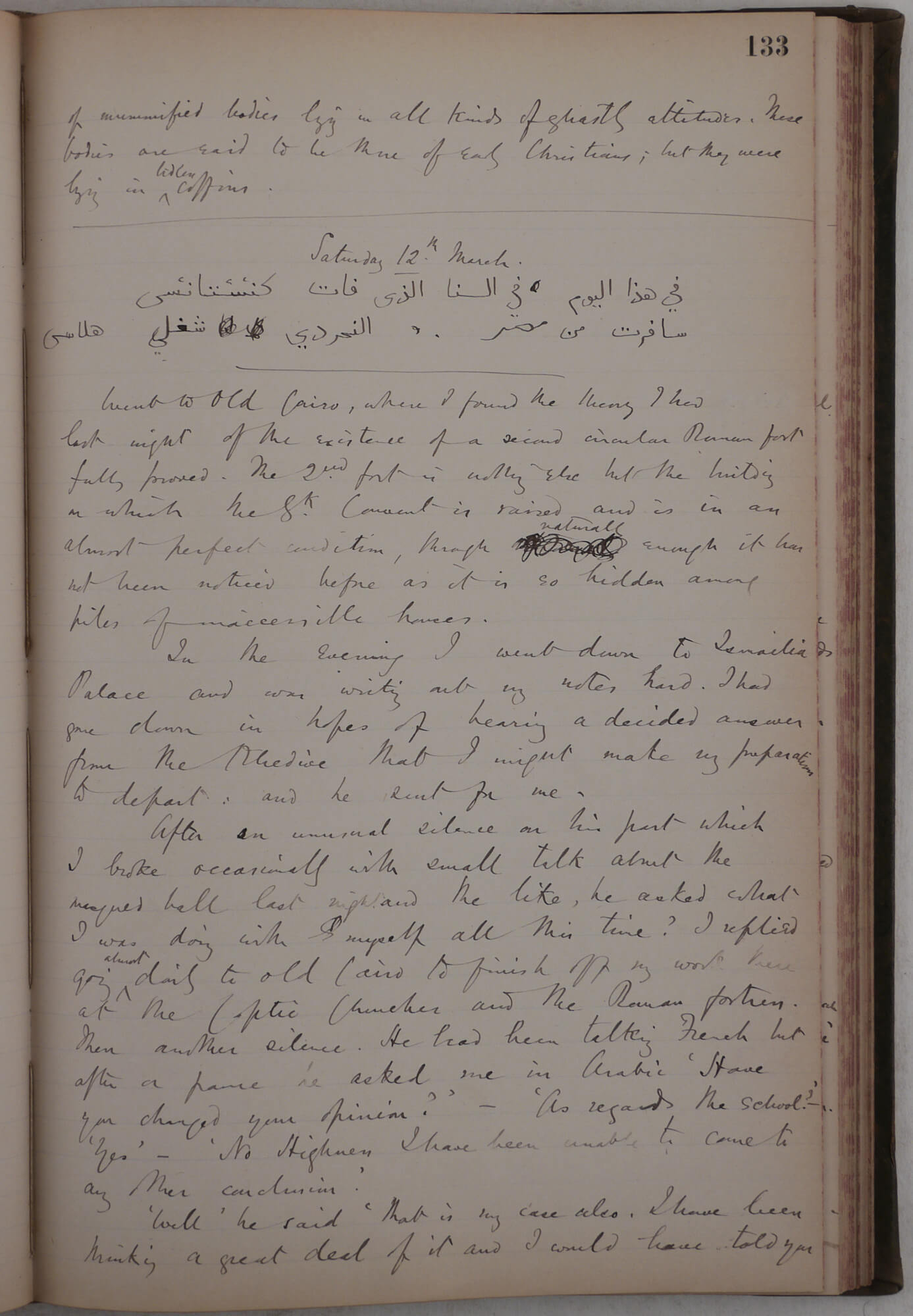

Excerpts from the diary:

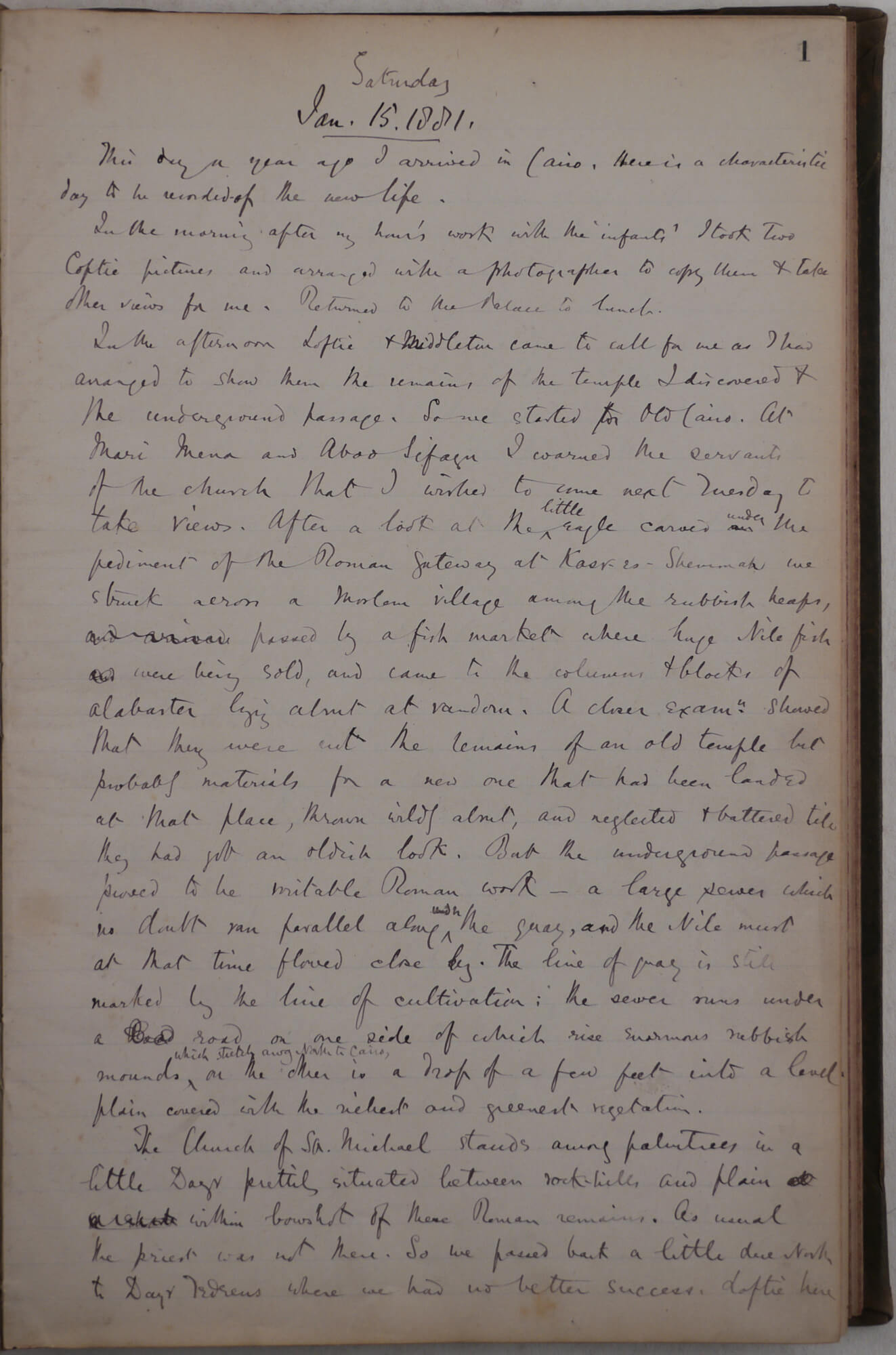

January 15: “The church of St. Michael stands among palm trees in a little Dagh [Dair] prettily situated between rock hills and plain within bowshot of these Roman remains. As usual the priest was not there. <…> At last the doorkeeper arrived with the usual wooden key, resembling a toothbrush with a set of spikes from the brush, and we entered. <…> All the pictures in the apse are quite new and of the type seen on the Cathedral screen. On the voussoir of the apse arch is a fresco of a winding Jesse tree with the figure of a saint in each bend of the stem; and in the s.w. corner of the nave is a curious recess divided into several niches or compartments in the centre of which is the angel Michael. Round the two pillars of this niche are tied votive offerings <…> plain handkerchiefs and gold-embroidered napkins, which are hung there by sick people to propitiate the angel. This is obviously the relic of a pagan custom.”

January 17: “It is true the K.[hedive] said that a certain daughter of Mohammad Ali (Tewfida Hanem, wife of Mohammed Bay, <..> a Keeper of the records), used to decoy handsome men into her palace by means of an Armenian woman, and then after taking her pleasure with them used to have them carried out & killed by her eunuchs. A young Frenchman was so […?] but took pistols, and when the eunuchs set upon him he shot the first and while the other hesitated he ran, climbed a tree and from that scaled over the palace wall and escaped. He wrote an account of his adventure in a book the Khedive now possesses. By the way, I omitted to say the Khedive has just recd. Intelligence of the whereabouts of the two eunuch-makers of Upper Egypt and has sent orders to catch, try and hang them if connected.”

January 18: “In the evening I went to the M-s. Mrs. M. is a Russian lady and while I was there she received a letter from her father, an Englishman in Russia, which seemed to agitate her greatly. She exclaimed passionately to herself ‘’Ah Lord Dufferin is deep’ and after reading a little further, retired quite overcome. Soon she reappeared smiling as ever. Russian no doubt has her ideas and plans about Egypt and her intrigues; and I believe there is great truth in some of the romantic stories one reads about women diplomatists in the Russian service.”

January 19: “… we [the Khedive and Butler] talked about the funeral of Mariette Pasha, the great antiquarian that took place today. He was carried into the church by native sailors or boatmen, most of whom were in tears. Thence, followed by all the ministers, the French consul, and all the notables of the place, the hearse went to the Museum where the body will rest for the night and will be buried tomorrow morning in the Museum garden by the Khedive’s express permission.”

February 5: “In the afternoon I went with Middleton to the Old Cairo and helped him to make a collection of pottery fragments for Wm. Morris the poet. The glaze is so beautiful and the colours so rich on this old Arab ware that the pieces one finds are like jewels, and Morris will be very glad if he can imitate them. At present, the art is quite lost in Egypt and does not exist in Europe.”

February 18: “Saw the Khedive in the evening and showed him the brief notice about Egyptian monuments which I had got put in the Athenaeum. He was pleased. He told me more about the Shah’s uncle. At the theatre last night he turned to the Khedive and said pointing to the audience ‘And are these all Europeans?’ ‘Yes, nearly all.’ ‘Dreadful, dreadful,’ said the Persian. ‘I am so sorry for Your Highness, but when the finances mend, of course, you will send them all out of the country?’ ‘Well,’ replied the Khedive, ‘the finances are a long way from mending so far as that; we have a dept of £60,000,000 and if I see it reduced to £30,000,000 I shall be quite content.’”

March 23: “A riot at Alexandria between the Greeks and the Jews. It is said that the Jews at the time of Passover always kidnap and kill a Xt. child to mingle his blood with their sacrifice. At Mr. Malet’s [British consul] request troops were sent down. The child who disappeared was found drowned & a verdict of drowning was brought in.”

March 25: “Started 7.30 to old Cairo with a photographer. Wind and cloud (!) & dump all against us. But I got a good view first of Dayr Babloon & […?], then descended & took notes of Babloon when occurred the strange coffee scene roughly described in my notebook. Thence I brought the photographer to the Church of Aboo Qeer where for long I vainly strove with the priest for the power of copying the magnificent Gospel case. At last, he yielded, and I suppressed the triumph which made my heart dance: it is the finest thing of the kind in Egypt, but few have seen it even. Then he produced the wonderful silver-wrought stole and maniple, both figured with angels and massive with metal; these I believe have never before been shown to a traveller <…> These also were photographed.”

March 30: “The photographs which I got taken on Monday all turned out miserable failures from the utter carelessness of the photographer. It was very disheartening after all the pains and extremes. He is ashamed of himself and today will try for better…”

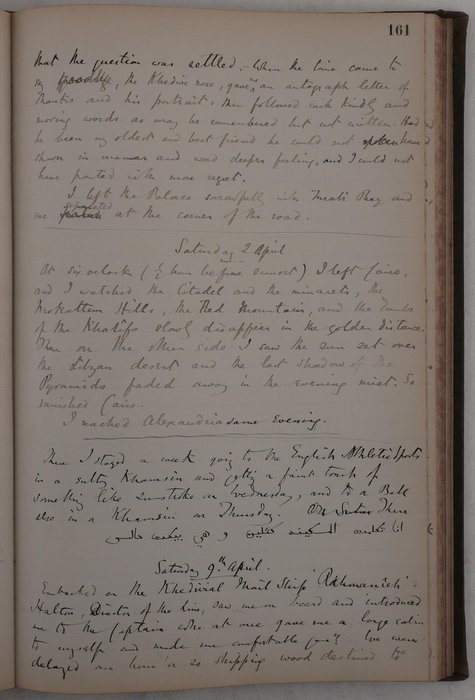

April 1 [about the last audience of the Khedive]: “In the evening I went down again to the anterooms whence I was sent for to see the Khedive. I presented him my book which he rose to receive and for which he thanked me very gracefully. <…> When the time came to say good-bye, the Khedive rose, game an autograph letter of thanks and his portrait. Then followed such kind and moving words as may be remembered but not written. Had he been my oldest and best friend, he could not have shown in manner and word deeper feeling, and I would not have parted with more regret…”

April 12: “At dinner, we heard some stories about the earthquake at Chios. The Greek govt. had sent 100 soldiers to excavate and the Turkish govt. of the island refused to let them land until an English and French man-of-war forced him. The Khedival Agent was buried in ruins by the first shock and an opening was made for him at the second. A woman was dug out alive after 3 days of internment. She was clinging to her dead husband with her children all dead around her <…> An Englishman was on the 3rd store of an Inn overhanging the sea; the moment the first shock came he leapt off the balcony into the sea and was saved: the next minute the Inn crashed down in ruins. It is stated that the shock was felt and a noise heard from Smyrna to Athens and in all the islands round. Yet that the people in the northern part of Chios were quite unconscious of it!”

April 14: “At 7:0 am we anchored opposite the town of Chios. From the vessel there were few signs of ruin: the houses for the wind part seemed standing uninjured. Before 8:0 I was ashore and the impression soon changed. First I walked to the right on landing and passed through crowds gathered in small huts and shops to an open space covered with tents in front of the old Venetian castle. Almost every home had some crack or break in it, the roof fallen I, a balcony tumbled down, gate pillars shattered – and here and there the whole structure had fallen in wreck and ruin. The people were all camping out in tents and rough wooden shanties were being raised on all sides, the houses were silent and deserted. <…> One man said the shocks still continued every three or four hours. Turning back, we passed through a quarter that had been more thickly peopled. Here the ruin was more striking. Not a single house seemed to have escaped. The old houses suffered most, some of them having nothing left but a single wall and a pile of stones and timber. Some of the streets are very narrow here as at Cairo, and all these narrow streets were blocked by masses of rubbish, bricks and stones and wood. Many of the buildings that looked at first unhurt were found to have huge cracks, running down the walls; others were leaning dangerously forward over the road and threatening to fall at every instant; and here and there where the ruins lay thicker came a horrible smell of dead bodies <…> English, French, Italian, Russian and American men-of-war were in the roadstead lending such relief as they could. Our own vessel landed provisions and took away a great number of refugees who crowded our already overcrowded decks, even blocking the light out of the saloon…”

April 20: “At dinner we had a dervish sitting at table in his large loose woolen robe and high conical hat: a big fine man. He was roughly acquainted with the use of know and fork, but not quite familiar with the order of events. During dinner he dived his hands occasionally into the dessert dishes and for dessert he eat pickles. He drank no wine, but the Captain said his look betrayed him, as a deep drinker of arraki. The Turks almost all without exception – men and women – drink terribly in open or in secret. After dinner, the Dervish went on deck and sat on a bench. I set myself down in a folding chair beside him. He asked me for a light which I gave him and he puffed at his cigarette. Presently he clapped his hands and his servants, two other dervishes, came and stood meekly beside him. He ordered them to fetch him fur, which he then made them put on him instead of his outer garment. The fur was an enormous robe lined with ermine or some white skin. When he sat down again, one of the servants brought in his ring and put it on his finger, and the Dervish smoked in state, occasionally deigning to speak a word with the servant who sat opposite him on a low cable-post with folded hands, worshipful eyes and lips always ready with a profound “Effendum.” Clearly, this was a great man. It seems he is a sort of Turkish Garter King at Arms – the man whose office it is to gird the Sward of State upon the Sultan’s thigh at the coronation.”

April 22: “Anchored in Smyrna at 7:0 a.m. There I left the good ship Rahmanieh and the Captain saw me ashore. At the custom-house, the Captain pointed out a man who would take the bakshish, so I slipped 2 francs into his hand and escaped the trouble of having my luggage searched. It was all done in the most open way…”.