#M99

1874-1875

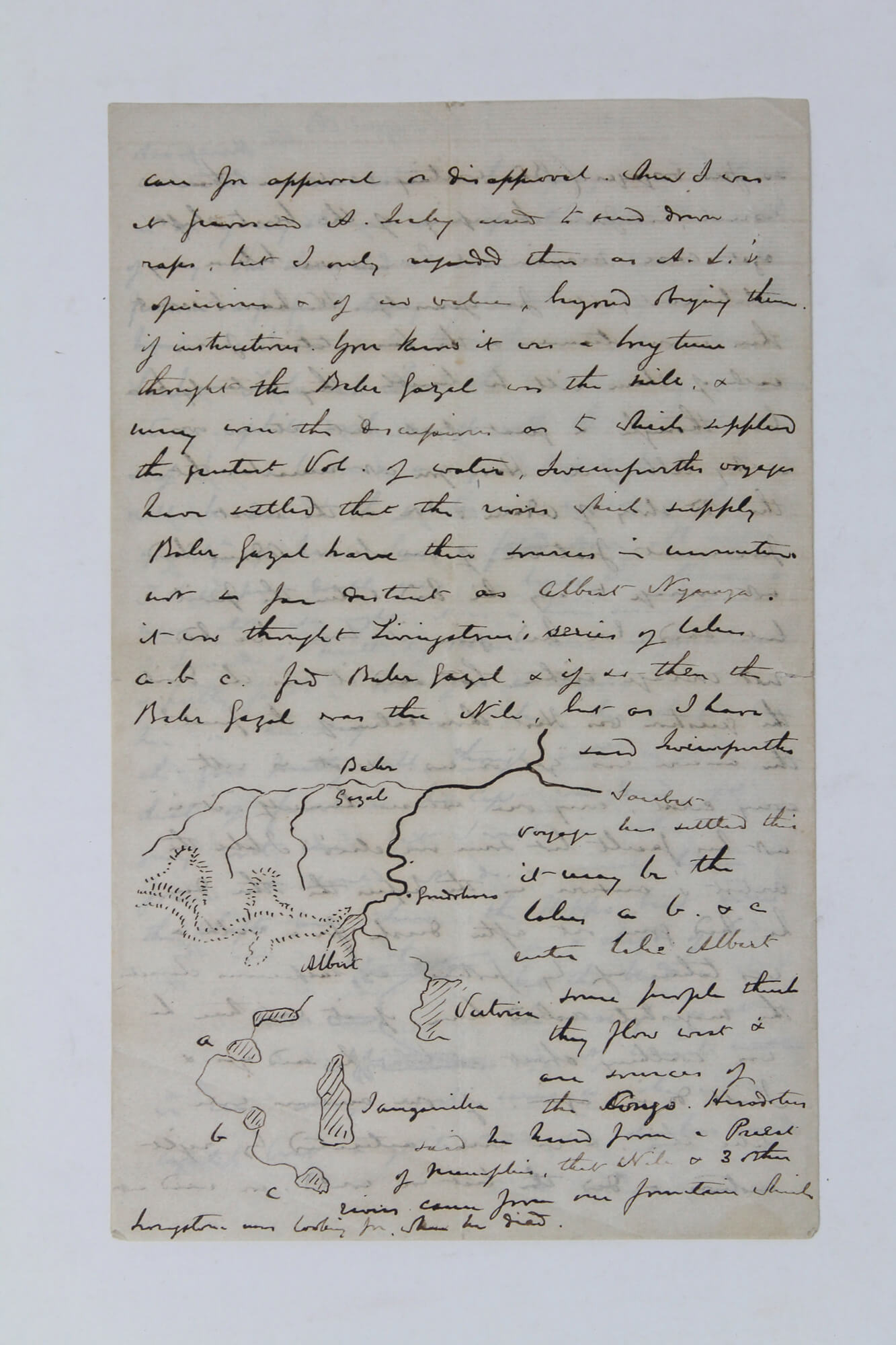

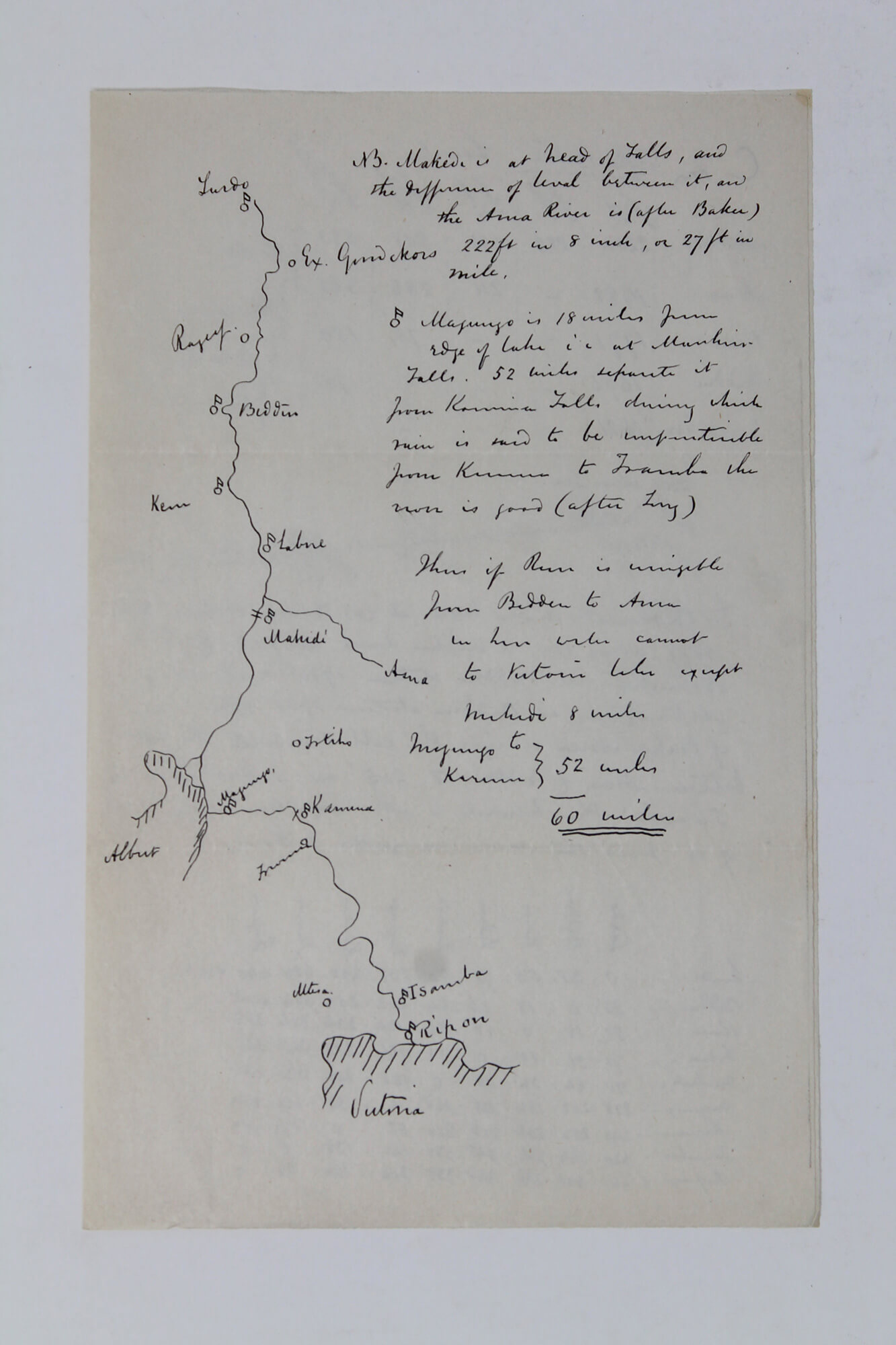

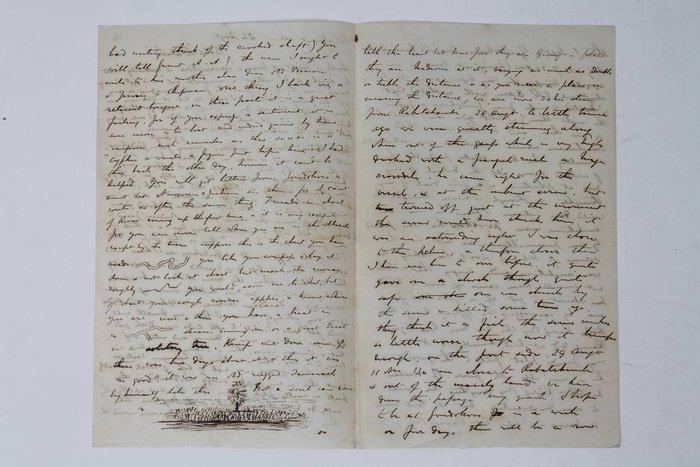

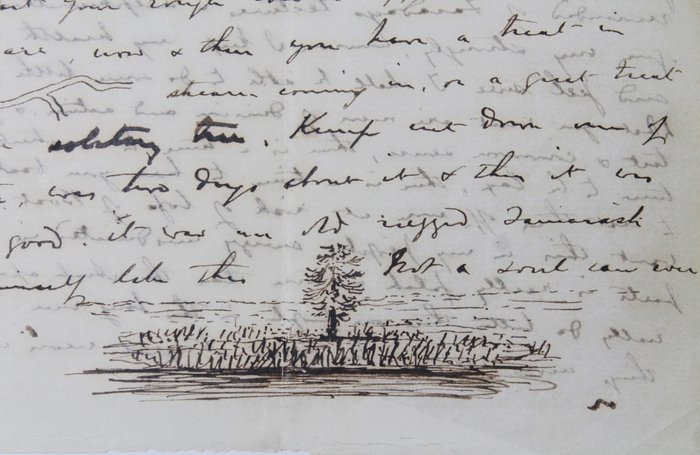

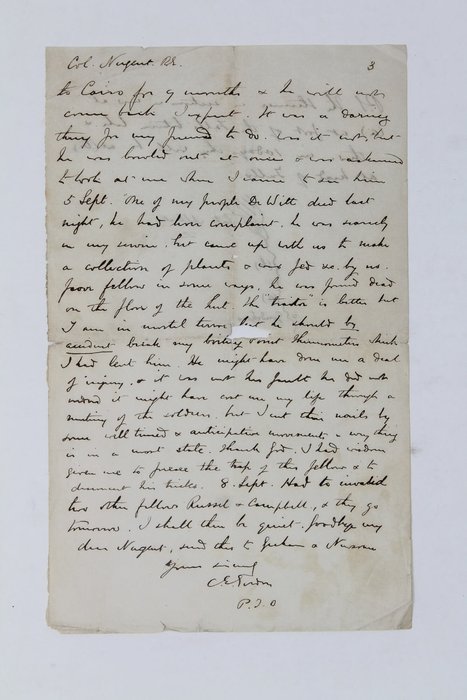

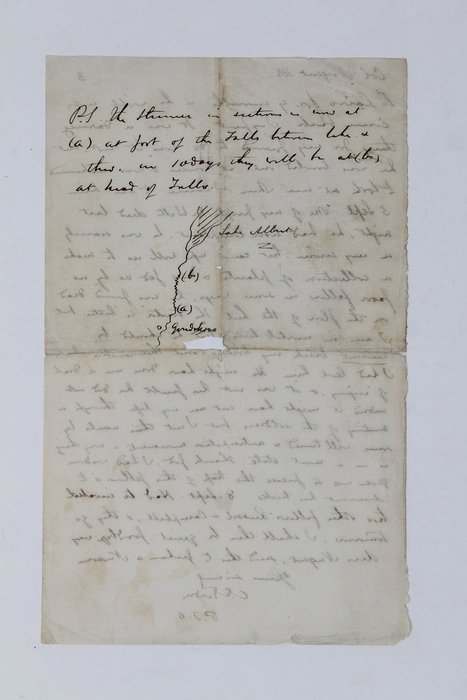

Each ca. 20x12 cm (7 ¾ x 5 in). 4, 4, 5,5 [= 13,5] pp. Brown ink on creamy laid paper. Six small ink sketches and maps in text. With a bifolium of creamy wove paper ca. 20x12,5 cm (ca. 8x5 in) with a hand-drawn map and manuscript notes in black ink. Watson’s letters: Berber, 27 September 1874; Gondokoro, 23 November 1874; Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo, 5 April 1875. Three Small Octavo letters (ca. 20,5x12,5 cm or 8x5 in). 4, 6, 4 [= 14] pp. Black ink on laid paper. All manuscripts comprise ca. 29 pp. of text. Fold marks, paper slightly age-toned, one leaf of Gordon’s letter with a minor loss in the centre affecting two words (but still readable), otherwise a very good collection of original expedition manuscripts.

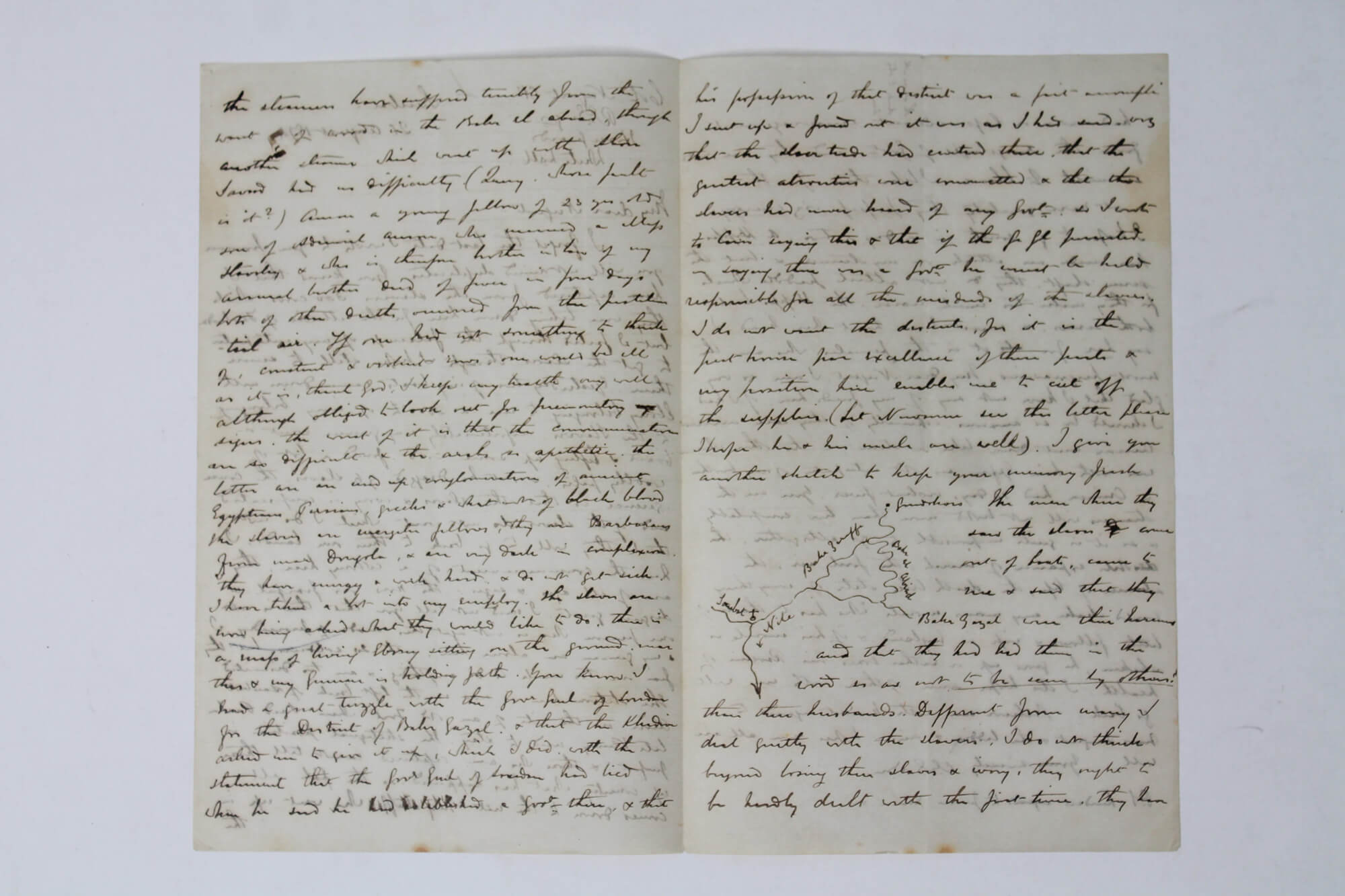

Historically significant collection of content-rich, original autograph signed letters (three are illustrated with several ink-drawn maps and sketches), providing a fascinating first-hand account of General Charles Gordon’s expedition up the White Nile in 1874-1876. Having become the second governor of the Egyptian province of Equatoria after Samuel Baker (1821-1893), Gordon, for three years (February 1874 – October 1876), travelled along the upper reaches of the White Nile and its tributaries. The main purpose of this series of exploratory trips was to expand the authority of Ismail Pasha’s Egypt to the entire Nile basin in the Great Lakes region (modern-day Uganda) and to suppress the local slave trade. Gordon travelled as far as Lake Albert and Lake Kyoga, establishing several military posts, including Lardo (Lado), where he moved the provincial capital. He managed to reduce the slave trade in the region but didn’t eliminate it, with slave traders continuing to operate in the Bahr el-Gazal basin, Kordofan and east of the Blue Nile. Gordon travelled up the Nile on river steamers, which were dismantled and carried over the jungle to Duffle, to establish transportation to Lake Albert.

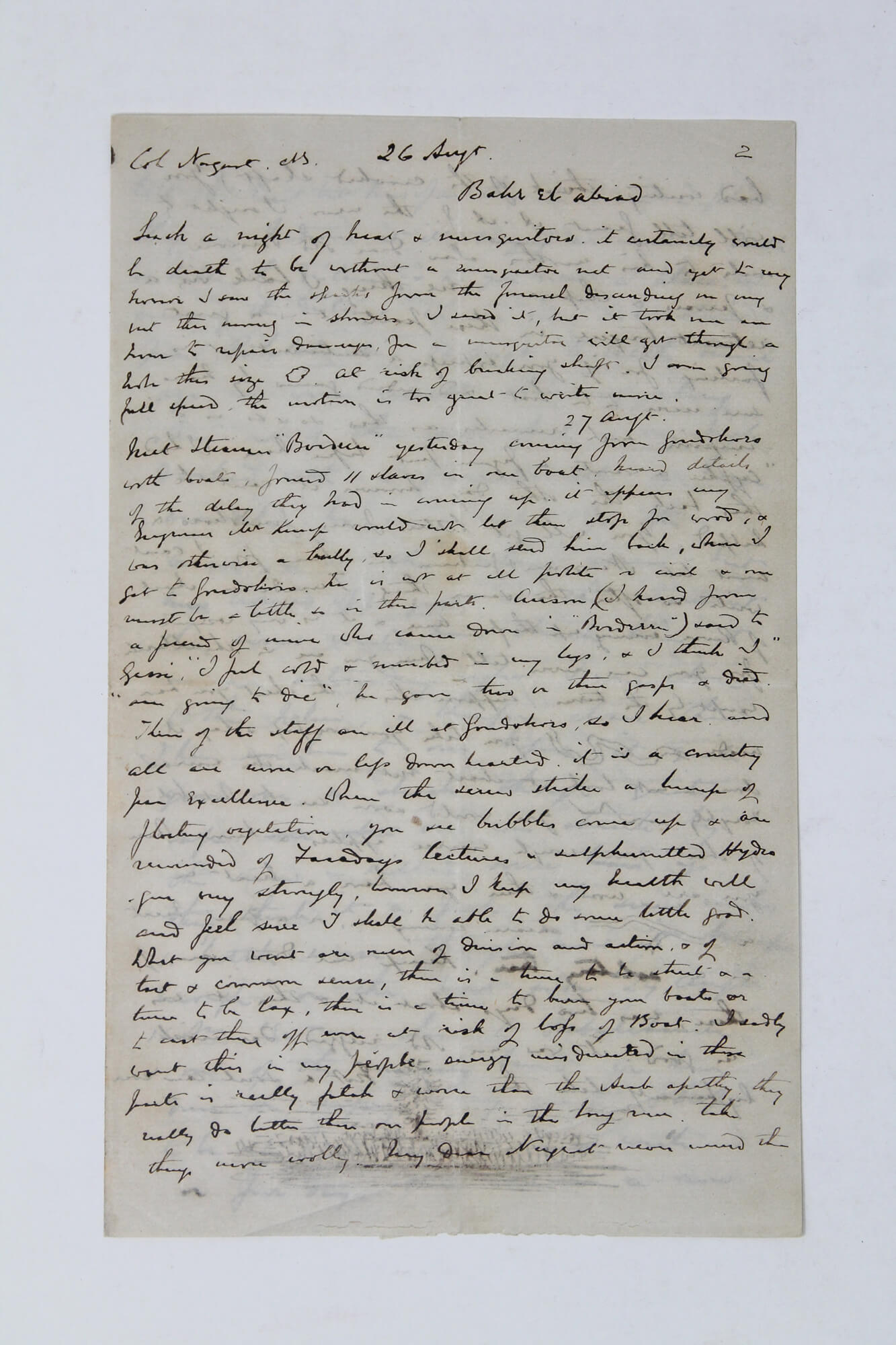

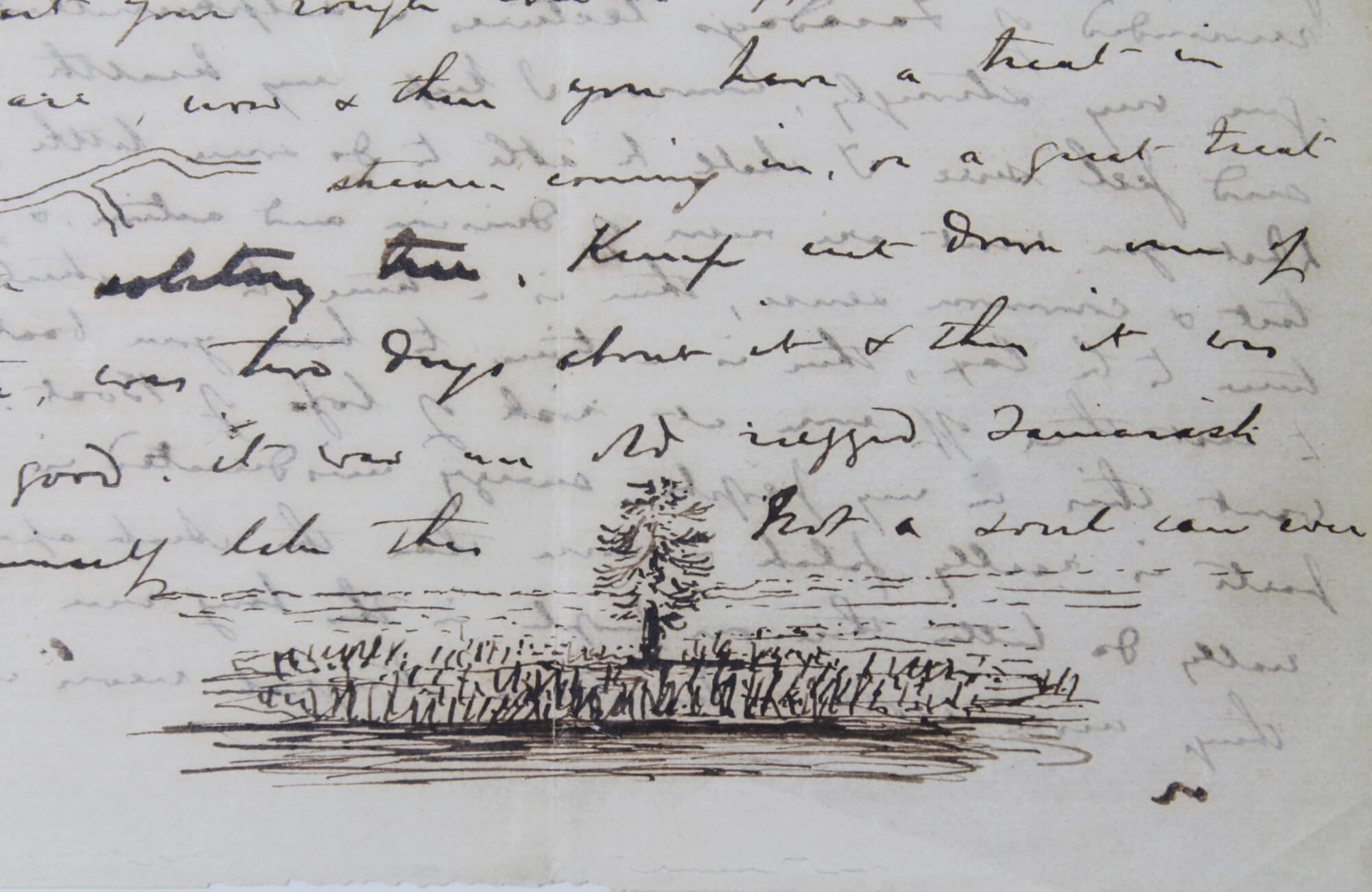

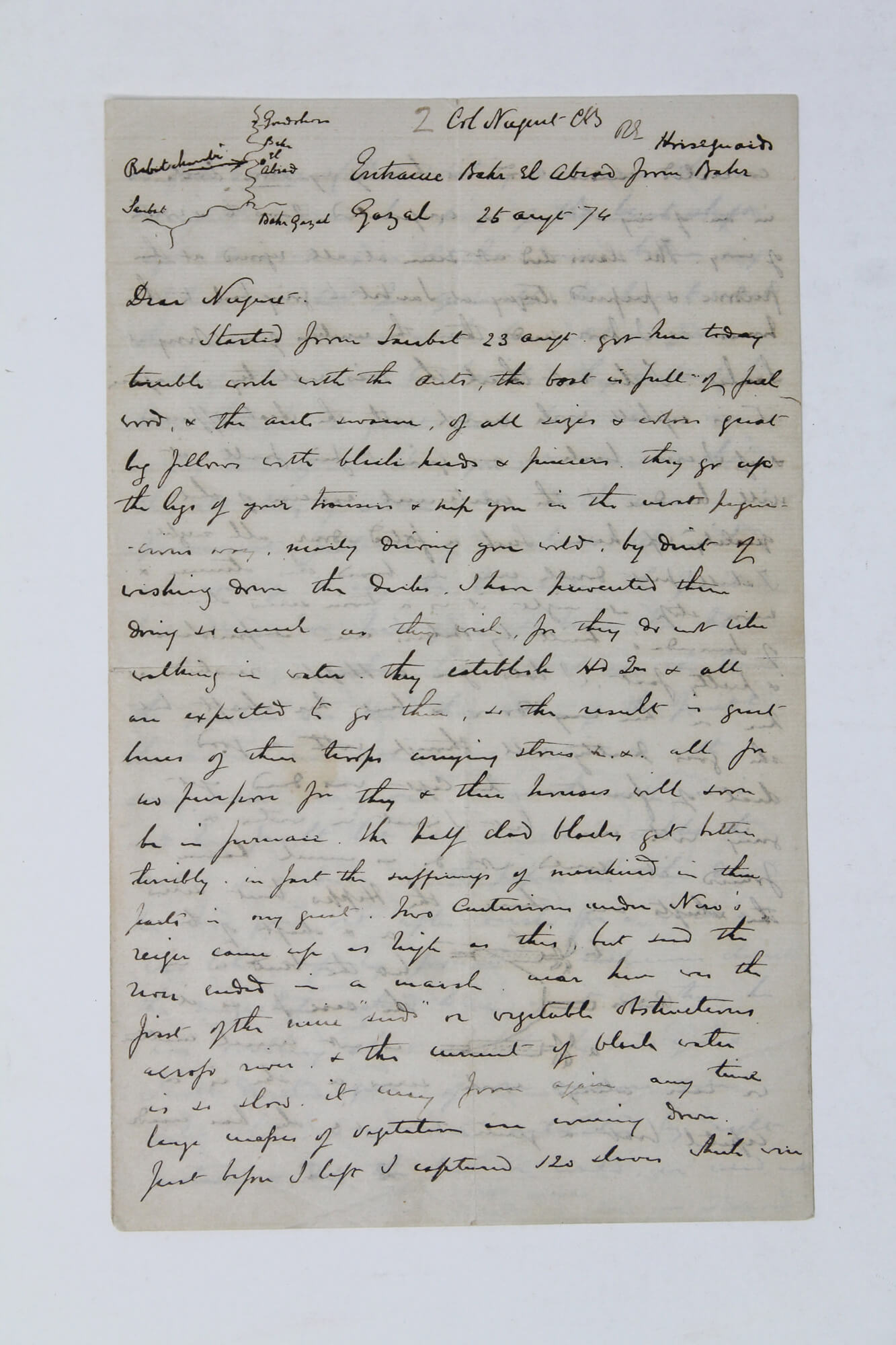

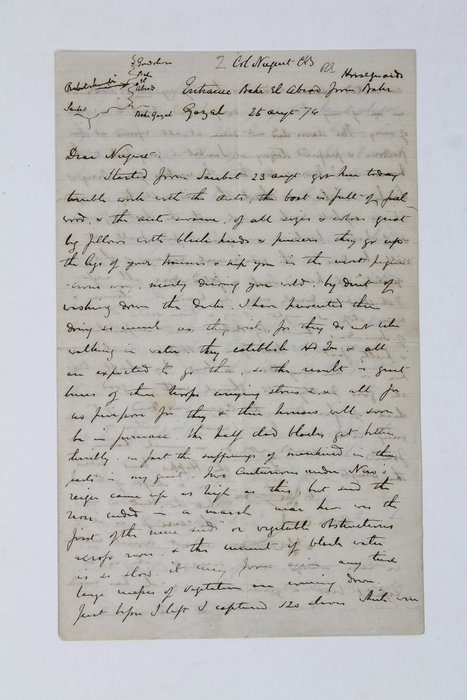

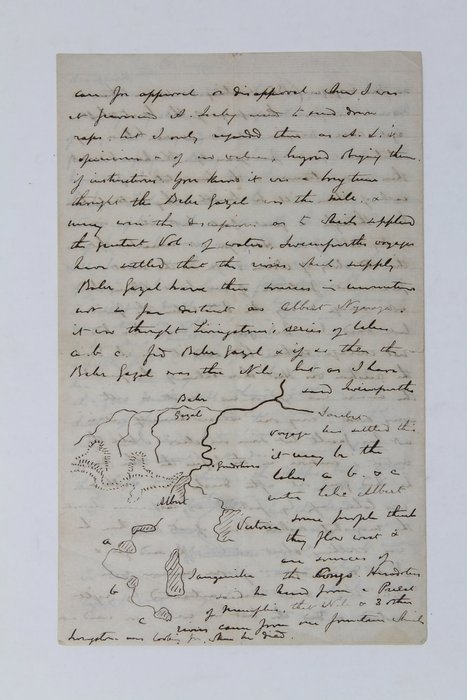

The collection includes three extensive letters written by Gordon (in all ca. 13,5 pages of text) and vividly describing his travel across the territory of modern-day South Sudan from late August to early September 1874. He went up the White Nile from the mouth of the Sobat (Saubat) River, the northern boundary of Equatoria, to the provincial capital in Gondokoro near modern-day Yuba. Because the more direct route via the Bahr el Zeraf arm of the White Nile was blocked with “sudd” or floating vegetation, Gordon had to go via the longer route up the Bahr el Abiad via its confluence with Bahr el Ghazal. He travelled by steamer, thus becoming the second person to do it after Samuel Baker, who steamed up the White Nile to Gondokoro in 1870. In the letters addressed to his friend Col. Sir Charles Nugent (1827-1899), Gordon talks about his plans, difficulties of moving forward because of floating vegetation and a hippo which damaged his steamer, abolished slaves, confiscated ivory, “pugnacious” ants which infested his steamer, vicious mosquitoes, a crocodile which tried to attack the steamer, mistaking its screw for a fish, deaths of Gordon’s companions and servants of fever (most likely, of malaria), intrigues of Egyptian officials, &c. His handwriting sometimes gets worse, and he apologizes for that, blaming his steamer’s bumpy movement after the hippo attack.

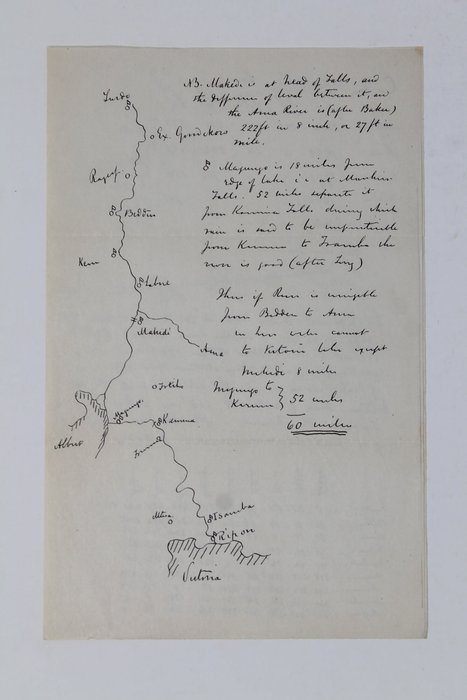

There is also a separate bifolium with a sketch map drawn by Gordon and following the White Nile from Largo (Lado, north of Gondokoro) to Ripon Falls. The map marks the main stations (Rigaf, Bedden, Labue, Makidi, Magungo, Isamba, &c), a part of the Asua River and the northern tips of the Albert and Victoria Lakes. The extensive notes talk about the difference in sea levels of different stations, the distance between them, and the navigability of the river. “Makidi is at head of Falls, and the difference of level between it and the Asua River is (after Baker) 222 ft. in 8 miles, or 27 ft in mile. Magungo is 18 miles from edge of Lake, at Murchinson Falls. 52 miles separate it from Karuma Falls, during which river is sad to be impenetrable, from Karuma to […?] the river is good…”

Three letters by a member of Gordon’s party, Lt. Charles Watson describe his experiences in Equatoria and Sudan in autumn 1874 – sprint 1875. Watson and his companion Lt. W.H. Chippendale joined Gordon’s party in Gondokoro in November 1874 and travelled with him up to Rigaf (Rejaf, south of Juba) but had to return to Cairo in January 1875 due to sickness. Watson’s letters provide more details on Gordon’s plans, the illness and deaths of his party members and the difficulties with native staff he experienced in Gondokoro. His account of Gordon’s expedition with the excellent detailed map of the White Nile from Khartum to Rejaf was published by the Royal Geographical Society (Watson, C.M., Strachan, R. Notes to Accompany a Traverse Survey of the White Nile from Khartum to Rigaf, 1874// The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 46 (1876), pp. 412-427). Later Watson took part in the Anglo-Egyptian War (1882) and served in the Egyptian army (1882-1886). He was a member of the Royal Geographical Society since 1875 and the Palestine Exploration fund since 1905 (see more: Obituary: Sir Charles Wilson// The Geographical Journal. Vol. 47, No. 5 (May 1916), pp. 387-389).

The recipient of Gordon’s letters, Colonel Sir Charles Nugent, served with the Royal Engineers and took part in the Anglo-Egyptian War. He received the Order of the Bath at Windsor Castle from Queen Victoria in November 1882.

Overall an important collection of original expedition letters from the famous Gordon Pasha, Governor General of Sudan, killed at the end of the Siege of Khartum (1885), providing a first-hand account of his exploration of the upper reaches of the White Nile in 1874.

Excerpts from Gordon’s letters:

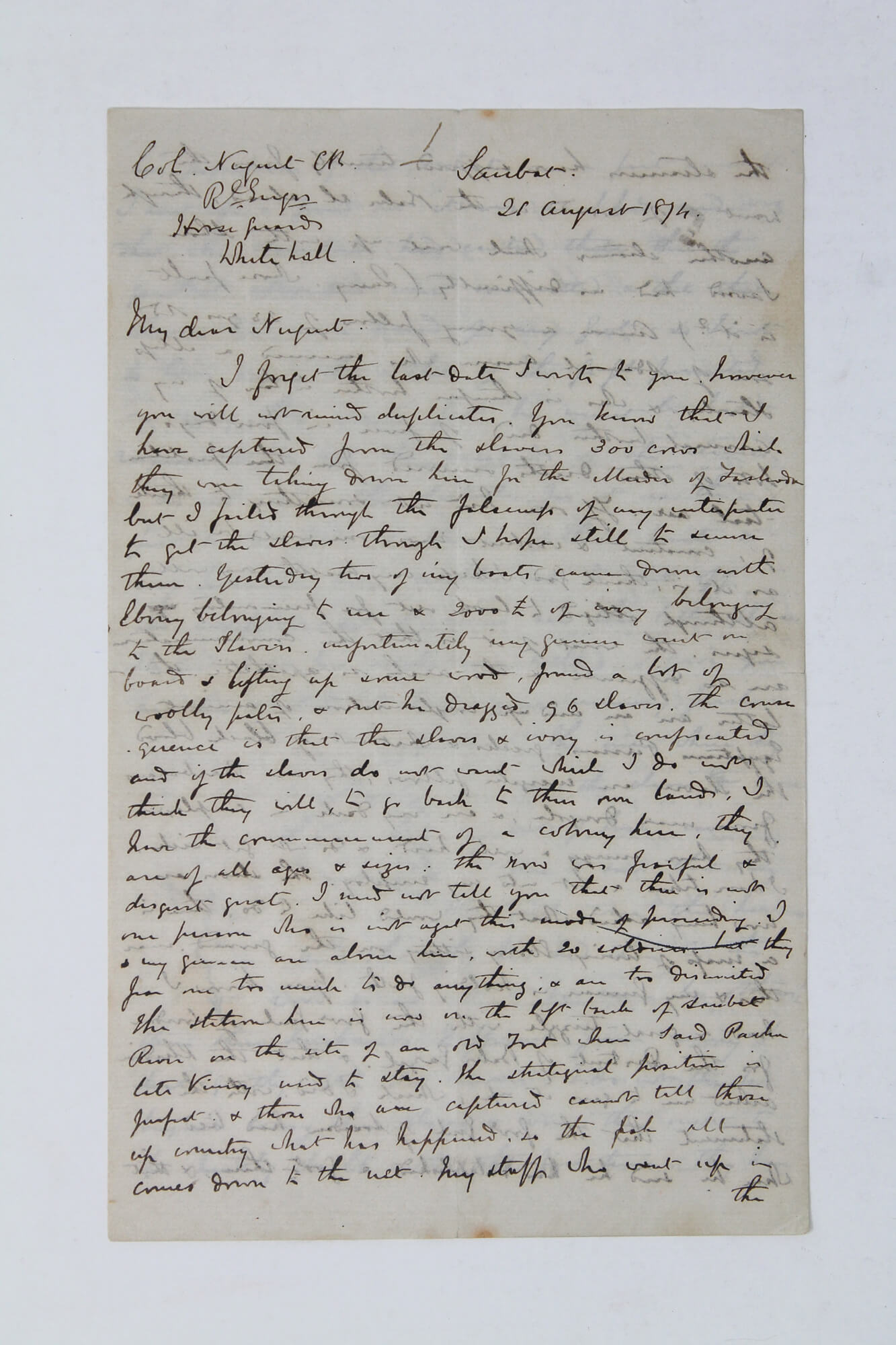

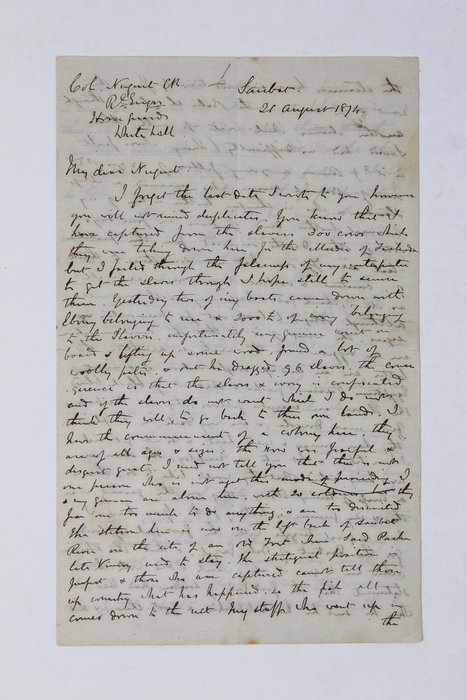

21 August 1874, Saubat River:

“<…> Yesterday two of my boats came down with Ebony belonging to me & £2000 of ivory belonging to the slavers. <…> my gunman went on board & lifting up some wood, found a lot of woolly palm & out he dragged 96 slaves. The consequence is that the slaves & ivory is confiscated and if the slaves do not want which I do not think they will, to go back to their own lands, I have the commitment of a […?] Here, they are of all ages and sizes.<…>

The steamer now is on the left bank of Saubat River on the site of an old fort <…> The strategic position is perfect & those who are captured can’t tell those up country what has happened, so the fish all comes down to the net. My staff who went up the steamer have suffered terribly from the want of wood from Bahr el Abiad, though another steamer which went up with Abou [Saveed?] had no difficulty. <…> [Amon?], a young fellow of 23 years old <…> died of fever a few days ago. Lots of other deaths occurred from the <…> air. <…> Thank God, I keep my health very well although obliged to look out for [preventory?] signs. The worst of it is that communications are so difficult <…>

I hope to go south in a day or two. A hippo has made an attack on my steamer & bent the screw shaft. They do not attach paddle wheels, for they make too much noise. The hippo bent both screws & must have hurt her head. I say her for it is the females who are the most persuasive…”

25 August, Entrance Bahr el Abiad from Bahr Gazal.

“Started from Saubat 23 Augt., got here today, trouble much with the ants, the boat is full of fuel wood & the ants swarm, of all sizes & colours, great big fellows with bluish heads & pincers. They get up the legs of your trousers & nip you in the most pugnacious way, nearly driving you wild <…>

Just before I left I captured 120 slaves which were concealed under wood in two of my own boats & in one of my steamers & confiscated £2000 worth of ivory. The slaves did not seem at all rejoiced at their freedom & prepared staying at Saubat & going back at their homes. <…>

I told you a hippo rushed in her [the steamer] on her way down & bent her shaft, but she goes pretty well though with a good deal of friction <…> Bad writing, i.e. worse than usual is from bumping of the bent shaft. <…>”

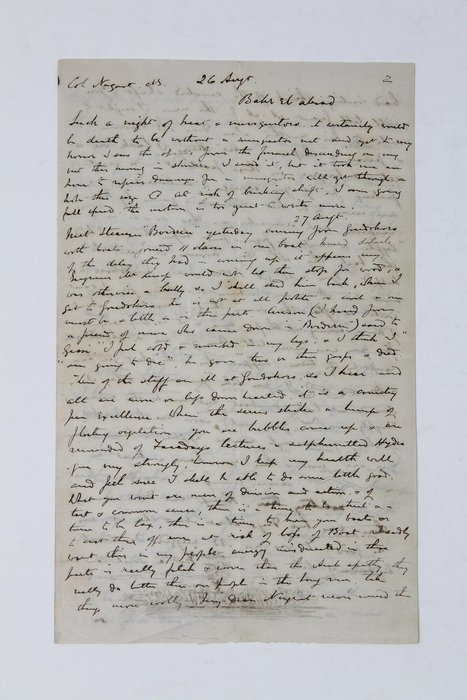

26 August, Bahr el Abiad.

“Such a night of heat & mosquitoes. It certainly would be death without a mosquito net <…> At risk of breaking shaft, I am going full speed, the motion is too great to write more.

27 August.

Met steamer [“Bordeen”?] yesterday coming from Gondokoro with boats, found 11 slaves in one boat. Heard details of the delay they had coming up. It appeared my Engineer Mr. Kemp would not let them stop for wood, & was <…> a bully, so I will send him back when I get to Gondokoro. He is not at all polite or civil & one must be a little so in this part. <…>

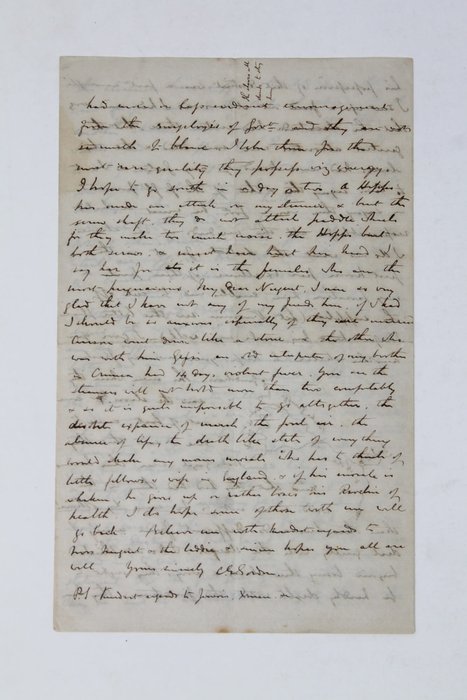

When the screw strikes a bump or floating vegetation, you see bubbles come up & are reminded of Faraday lectures <…>. I keep my health well and feel sure I shall be able to do some little good. <…> I made a chart of River coming up the first time & it is very useful <…>

28 August. A little time ago we were quietly steaming along when out of the grass, which is very high rushed <…> a huge crocodile, he came right for the vessel & at the unbent screw, but turned off just at the moment the screw could have struck him. It was an astonishing sight. <…> They think it’s a fish. The screw makes so little noise, though now it bumps enough on the port side.

29 August. We are close to [Rabatikembi?] & out of the marshy land. We have done the passage very quiet. I hope to be at Gondokoro in a week or five days.

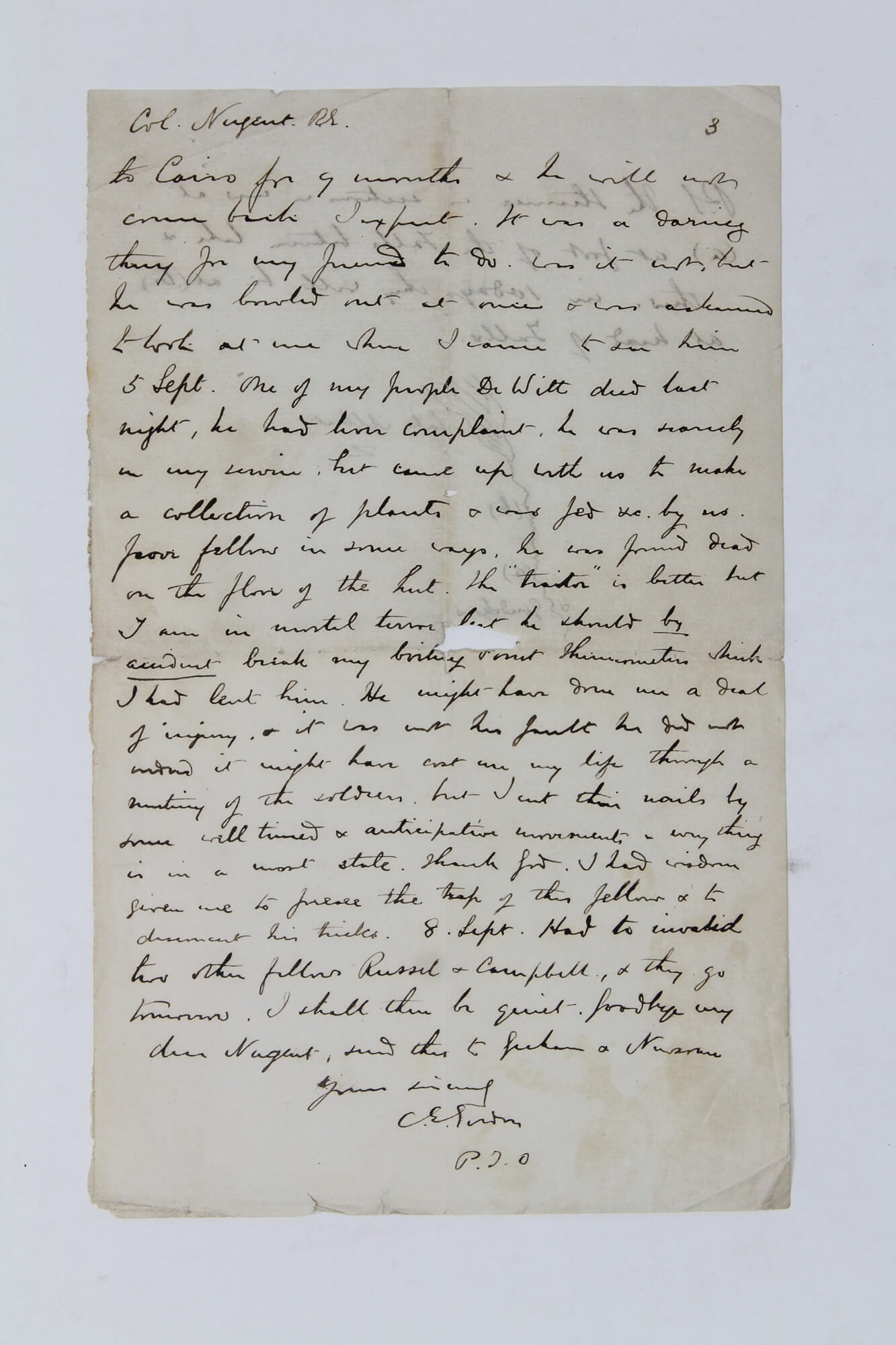

4 Sept. Gondokoro. Arrived here yesterday at 7.30 a.m. (having not been in agreeable temper the day before, owing to having stayed up till 3 a.m. with a stupid Capt. I halted 9 miles from Gondokoro & passed the night there). [A detailed description of him fighting intrigues by his interpreter and his talks to Raouf Bey].

5 Sept. One of my people Dr. Witt died last night, he had liver complaint, he was scarcely in my service, but came up with us to make a collection of plants & was fed &c. by us. Poor fellow in some ways, he was found dead on the floor of the hut. The “traitor” is better, but I am in mortal terror that he should by accident break my boiling point thermometer which I had lent him. He might have done me a deal of injury & it was not his fault he did not intend it might have cost me my life through the mutiny of the soldiers…

8 Sept. Had to invalid two other fellows, Russel & Campbell & they go tomorrow…”

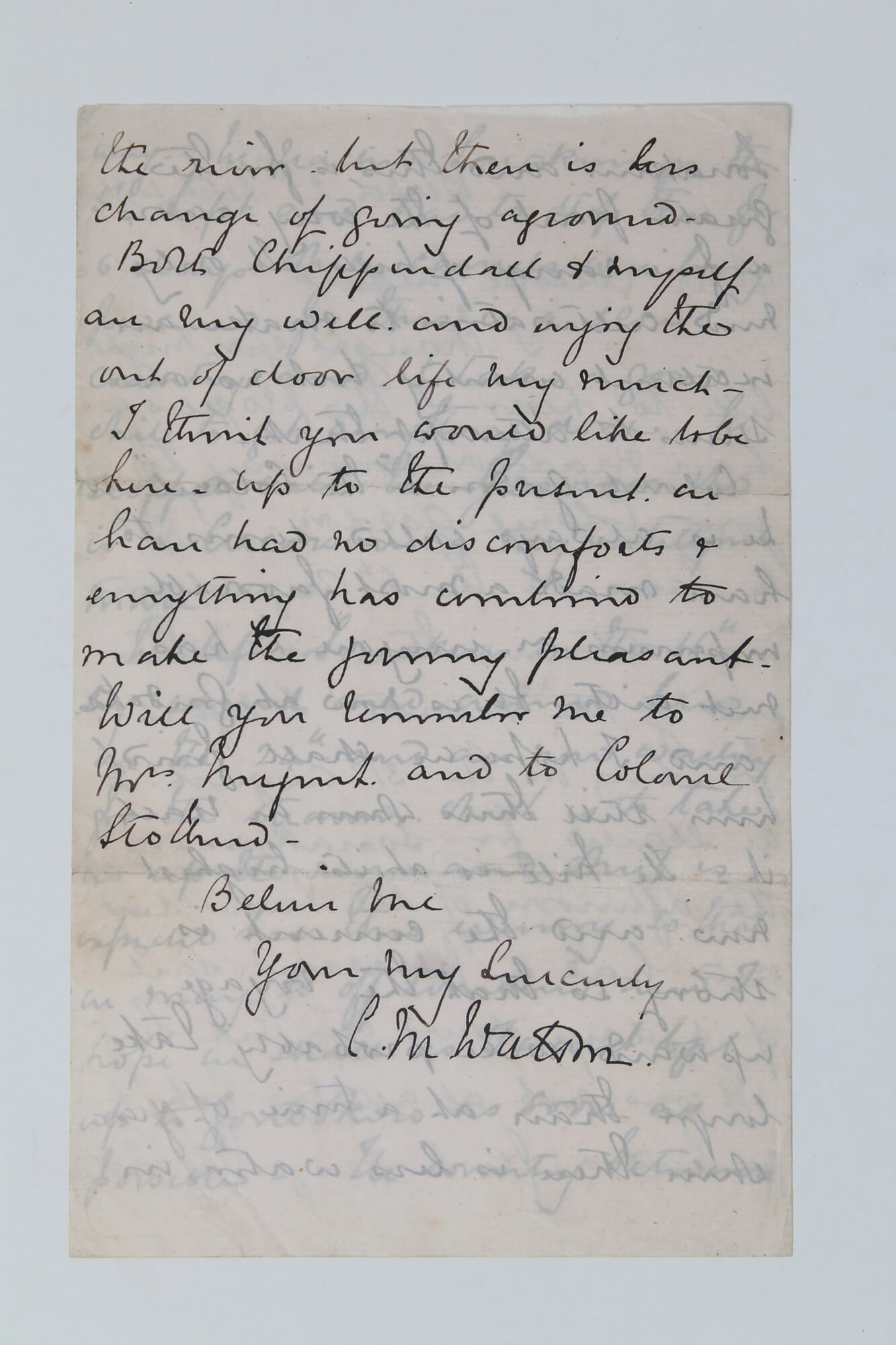

Excerpts from Watson’s letters:

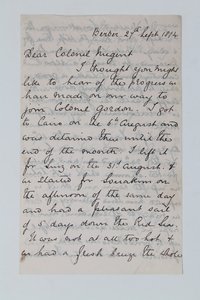

Berber, 27 Sept. 1874:

“Dear Colonel Nugent,

I thought you might like to hear of the progress we have made on our way to join Colonel Gordon. <..> We left Souakin on the 11th [September] by camel and arrive here on the 35th and are now waiting got the steamer which is to take us up the river <…> The country between Souakin and this, is for the greater part of the way across is fine range of hills. It only needs cultivation to make an excellent country, but on one seems to attempt that. Colonel Gordon, or “the Colonel,” as he is always called, seems to have made a most favourable impression on anyone he has met with. He is not at Gondokoro and I hope we shall find him still there when we reach it. The Nile is at its highest now and the current is strong, so that the voyage upwards will probably take longer than at a time of year when there is less water in the river. <…> Both Chippendale & myself are very well and enjoy the out of door life very much…”

Gondokoro, 23 Nov. 1874:

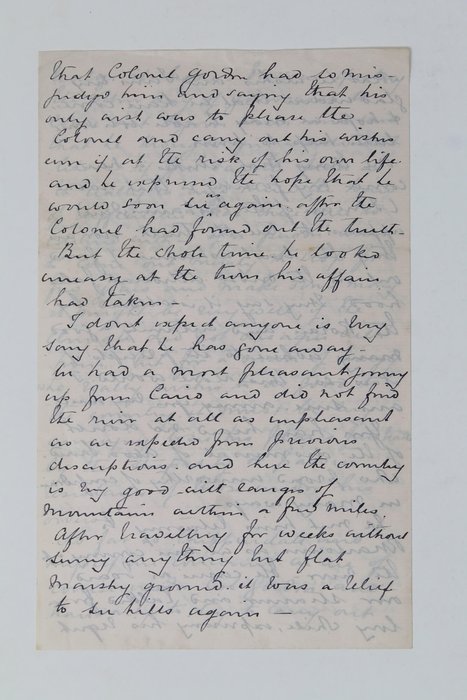

“<…> we have at last joined Col. Gordon after a longer journey we had anticipated before leaving England. We found him very well and hard at work, and he has a great deal to do, far more than would be necessary if he had to deal with Europeans. With people here, it appears difficult to get anything done unless you stand by and see it actually done in your presence. One has often heard of the laziness <…> of Egyptians and Arabs, but I did not realize it before. <…> for a man of energy who really wishes to do good to the country it must be very annoying to see his plans frustrated by the stupidity or passive resistance of those under this orders.

As far as Chippendale and myself are concerned, we are of course under Col. Gordon and have only to try to carry out what he wishes and I am very glad indeed that we have come & hope we may be able to do some little help to him. One thing that strikes a newcomer very forcibly is that no one (I mean of the Mohammedans) appears to tell the truth, or are they the least ashamed if found out in the most deliberate falsehood. They say it is allowed by the Koran and certainly a good many adhere to its principles if it is so. <…>

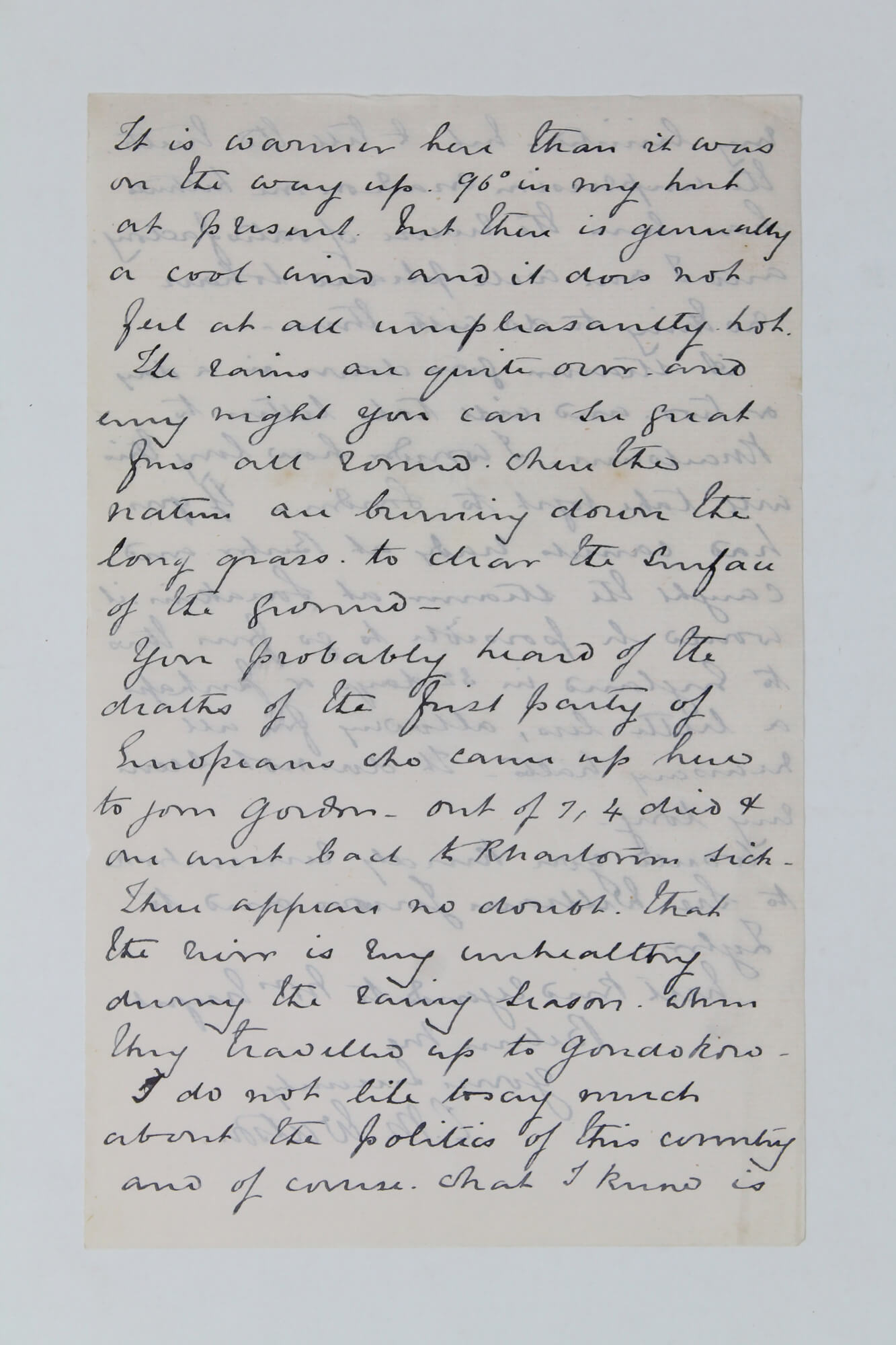

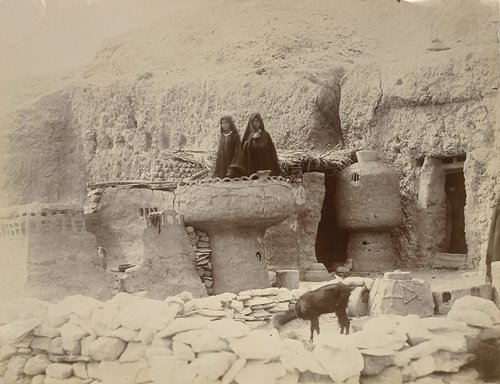

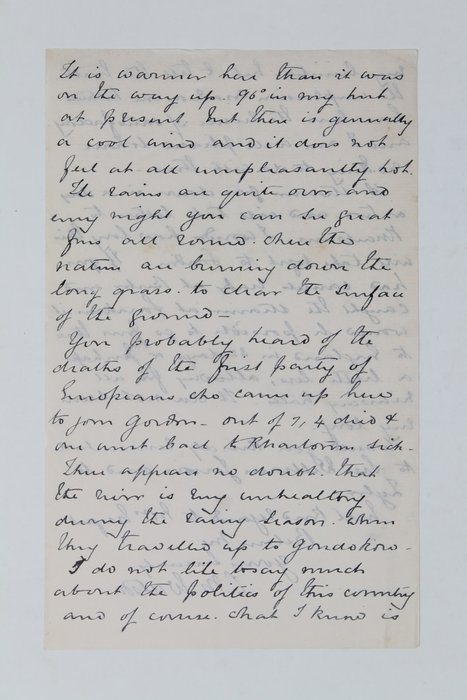

Here the country is very good with ranges of mountains within a few miles. After travelling for weeks without seeing anything but flat marshy ground it was a relief to see hills again. It is warmer here that it was on the way up, 96° in my hut at present, but there is generally a cool wind and it does not feel at all unpleasantly hot. The rains are quite over and every night you can see great fires all around, where the natives are burning down the long grass to clear the surface of the ground.

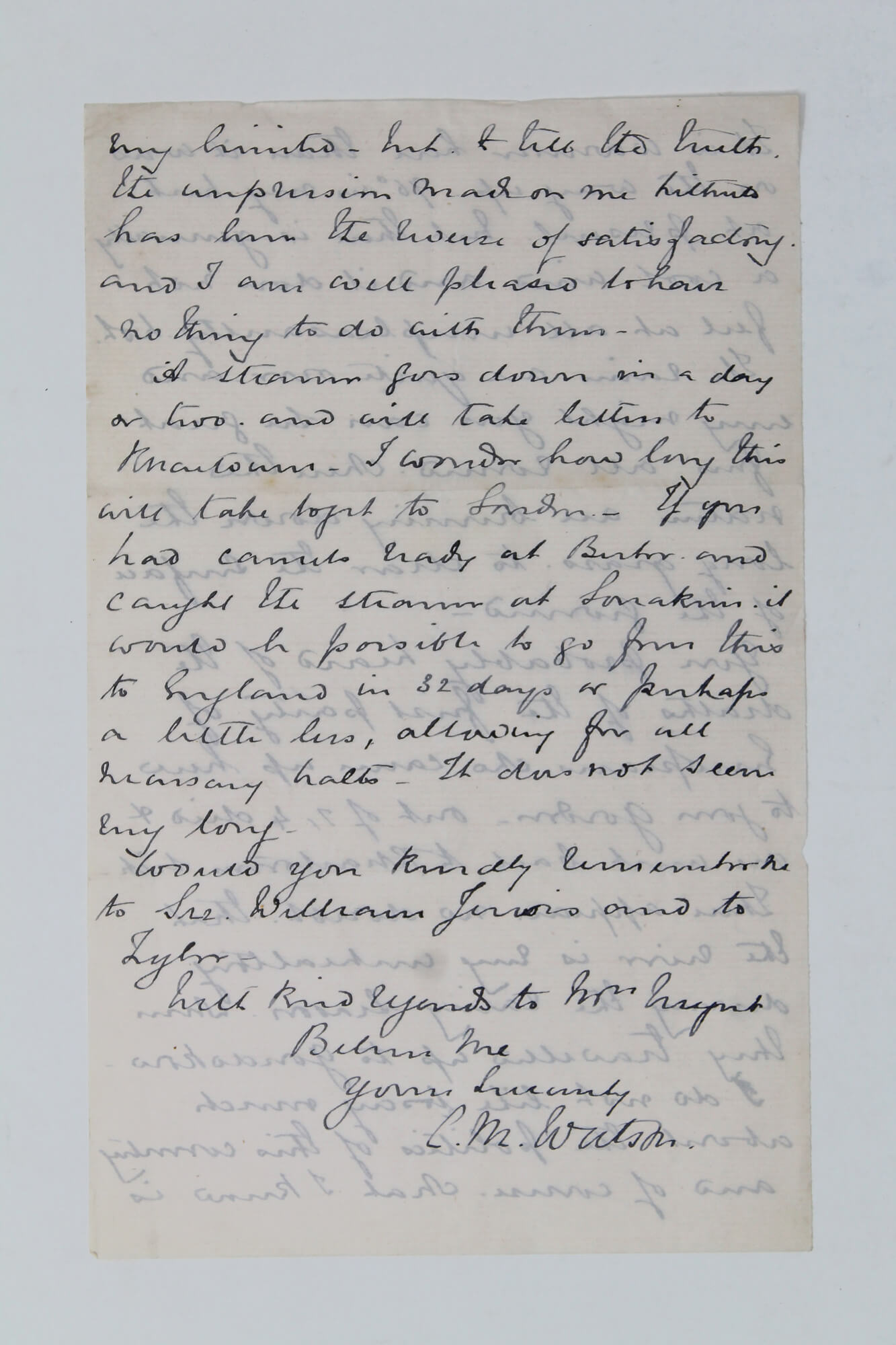

You probably heard of the deaths of the first party of Ethiopians who came up here to join Gordon. Out of 7, 4 died & one went back to Khartoum sick. There appears no doubt that the river is very unhealthy during the rainy season when they travelled to Gondokoro. I do not like to say much about the politics of this country and of course what I know is very limited, but to tell the truth, the impression made on me hitherto has been the […?] of satisfactory and I am well pleased to have nothing to do with them…”

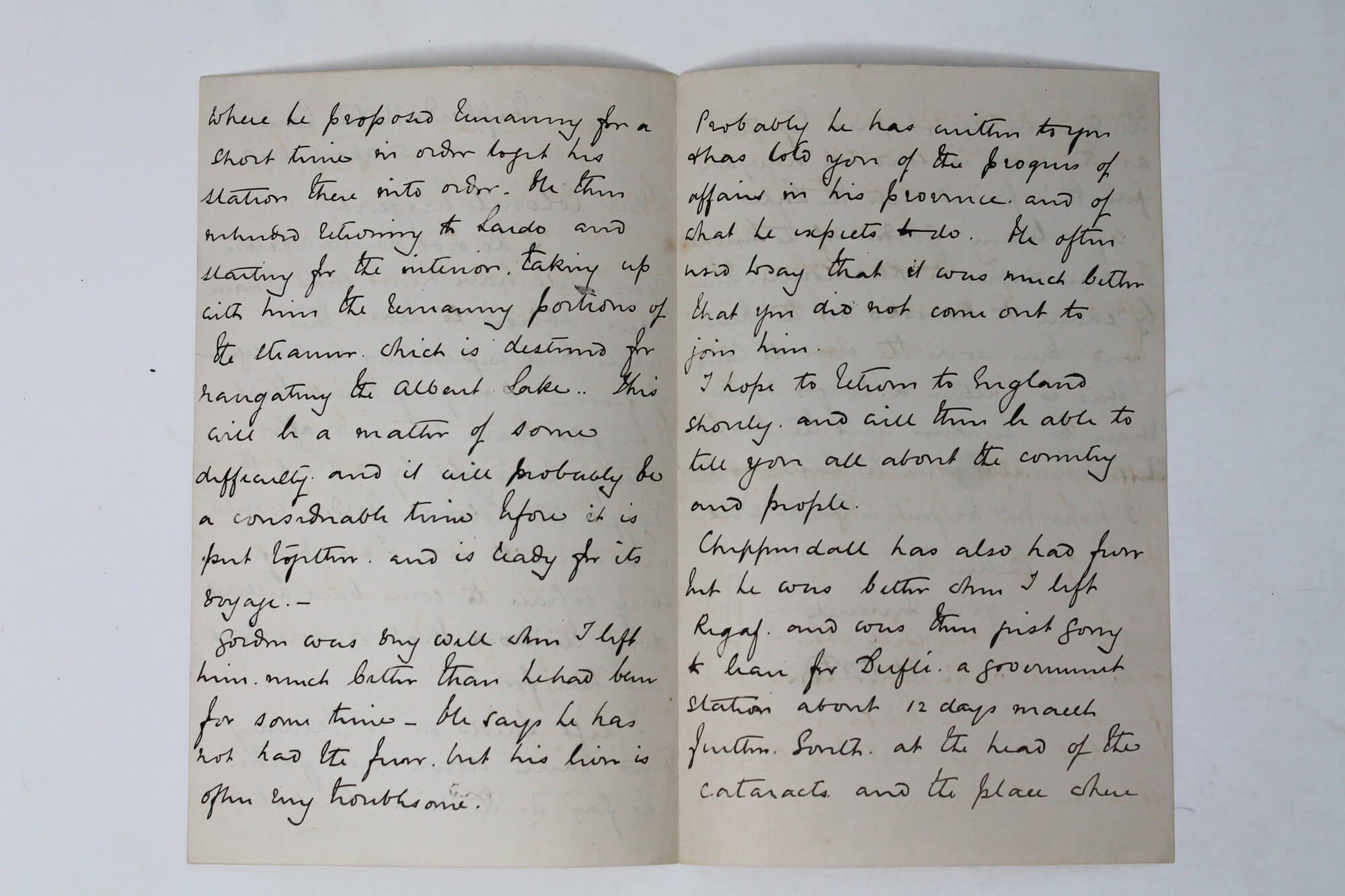

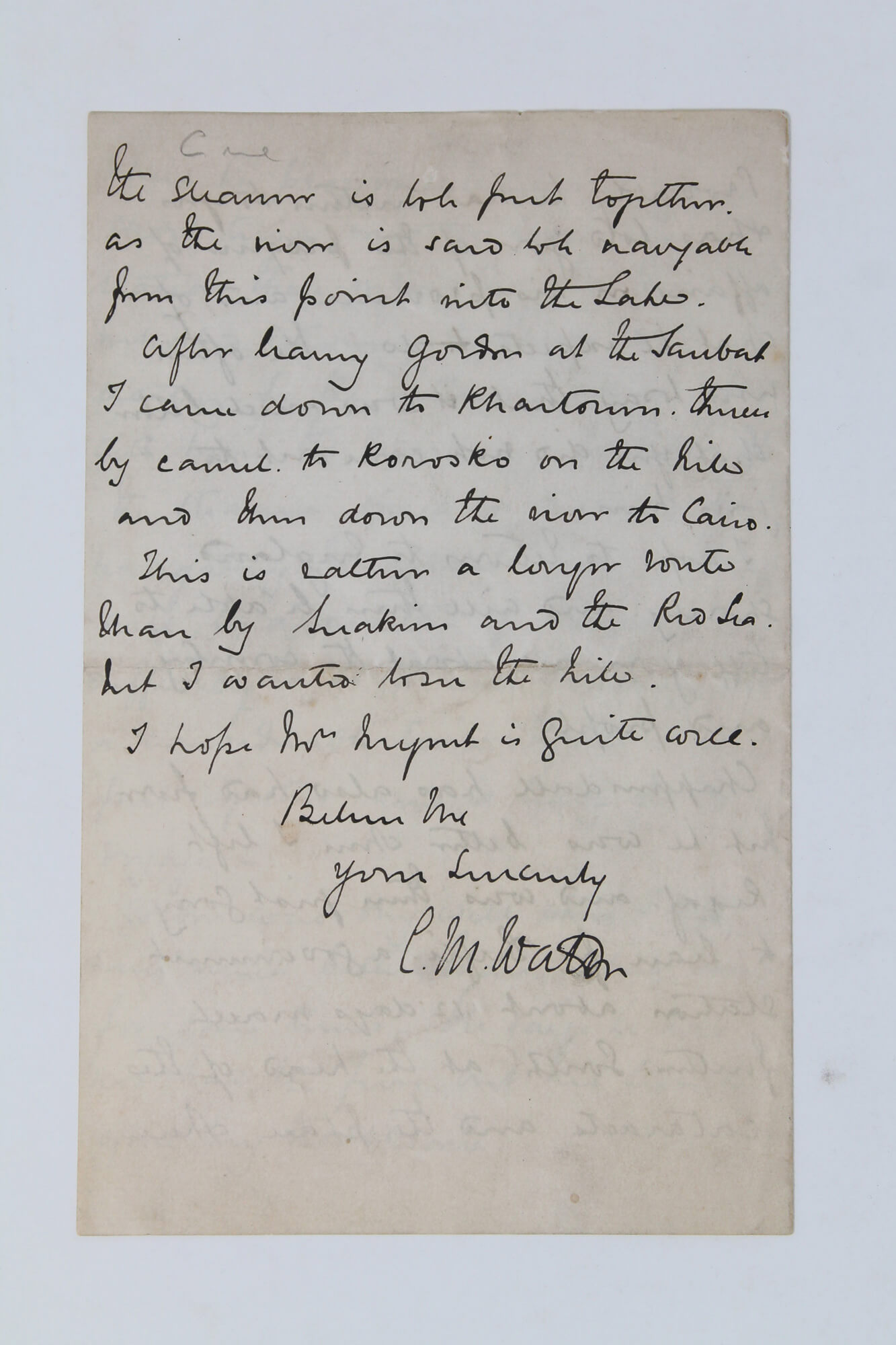

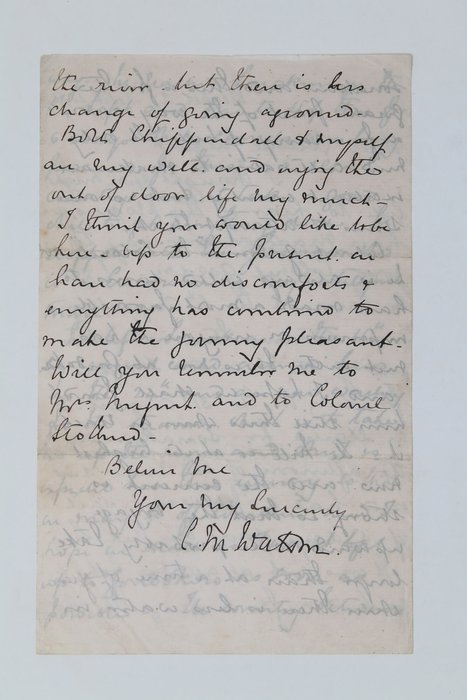

Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo, 5 April 1875

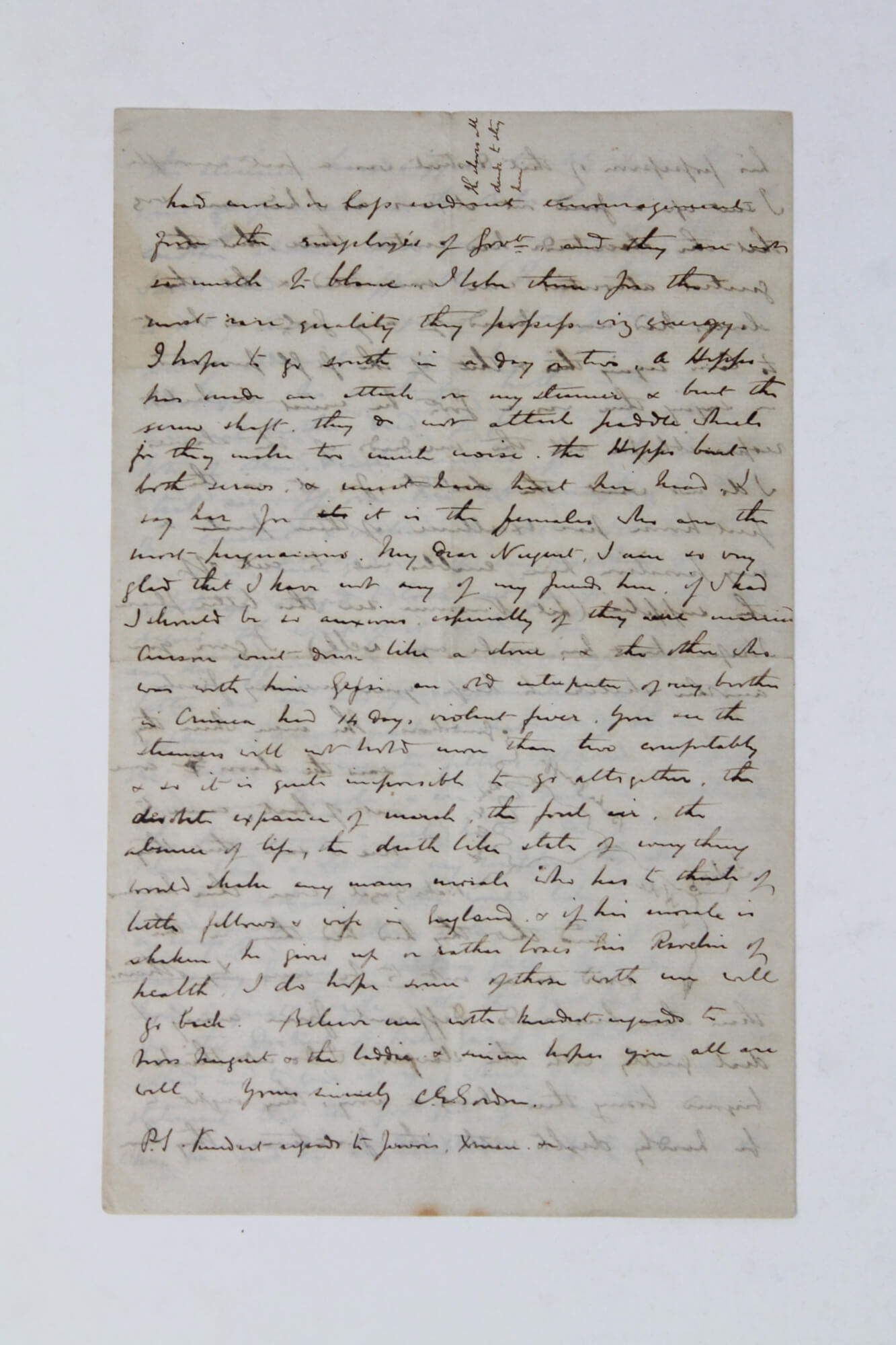

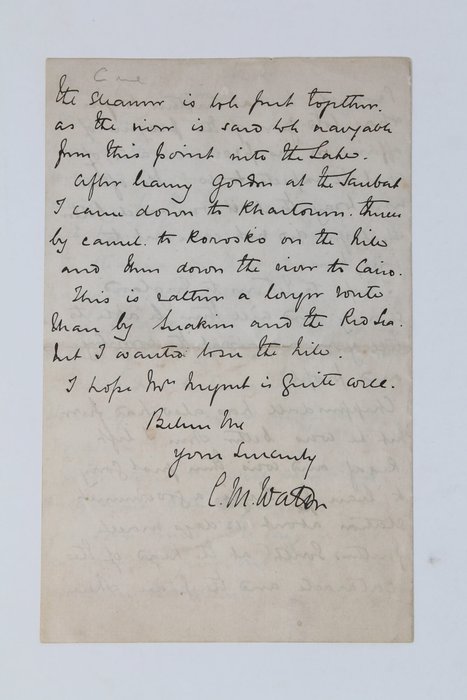

“I do not know whether you will have heard that I have been obliged to leave the White Nile expedition in consequence of fever. <…> I am very sorry to have to come back without doing the work that we were sent out here for. I left Lardo on 3d. January and came down with Gordon as far as the River Saubat, where he proposed remaining for a short time in order to get his station there into order. He then [intended?] retiring to Lardo and starting for the interior taking up with him the remaining portions of the steamer which is destined for navigating the Albert Lake. This will be a matter of some difficulty and it will probably be a considerable time before it is put together and is ready to its voyage.

Gordon was very well when I left him, much better than he had been for some time. He says he has not had the fever, but his liver is often very troublesome. <…> Chippendale has also had fever, but he was better when I left Rigaf and was then just going to leave for Dufli, a government station about 12 days march further south at the head of the cataracts and the place where the steamer is to be put together as the river is hard to be navigable from this point into the lake.

After leaving Gordon at the Saubat, I came down to Khartoum, thence by camel to Korosko on the Nile and then down the river to Cairo. This is rather a longer route than by Suakin and the Red Sea, but I wanted to see the Nile…”.