#M49

1868

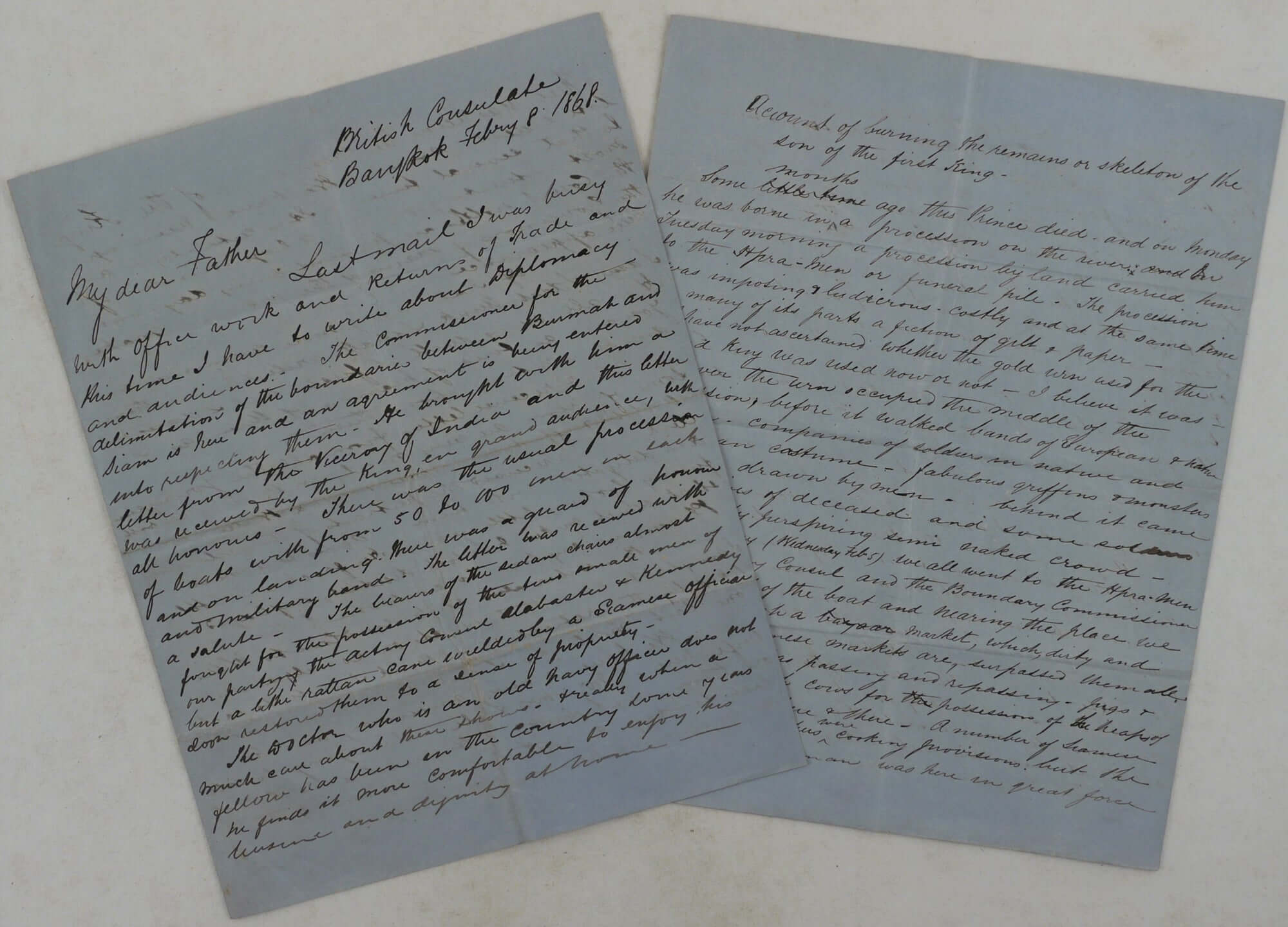

Two Quarto bifoliums (ca. 26,5x21,5 cm ). Brown ink on bluish paper. 4 + 4 pp. Of text. Fold marks, paper mildly age toned, but overall a very good pair of manuscript documents.

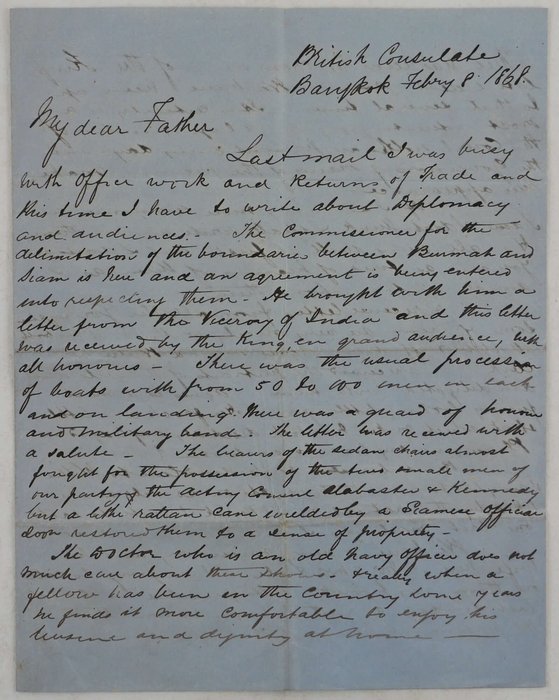

Historically interesting content rich letter written by a British diplomat in the Kingdom of Siam to his father. The narration starts with a description of the arrival of the “Commissioner for the delimitation of the boundaries between Burmah and Siam” (the Convention between the Governor-General of India and the King of Siam, defining the boundary between Siam and the Burmese province of Tenasserim, treaty signed on February 8, 1868, and ratified on July 3 the same year): “…[the Commissioner] brought with him a letter from the Viceroy of India and this letter was received by the King, en grand audience, with all honours. This was the usual procession of boats with from 50 to 100 men in each and on landing there was a guard of honour and military band. The letter was received with a salute. The bearers of the sedan chairs almost fought for the possession of the two small men of our party, the acting Consul Alabaster & Kennedy, but a <…> rattan cane wielded by a Siamese official soon restored them to a sense of propriety”.

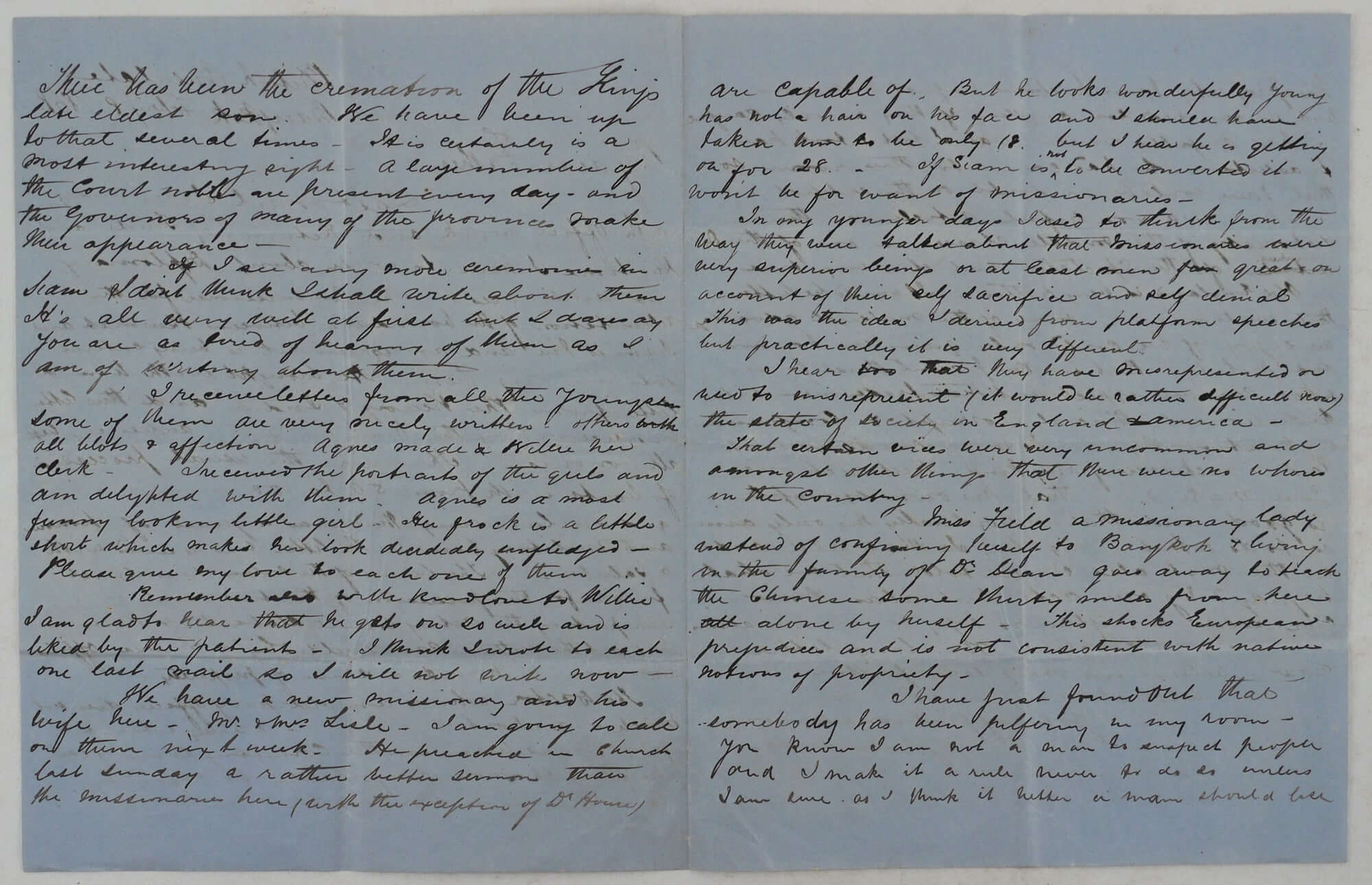

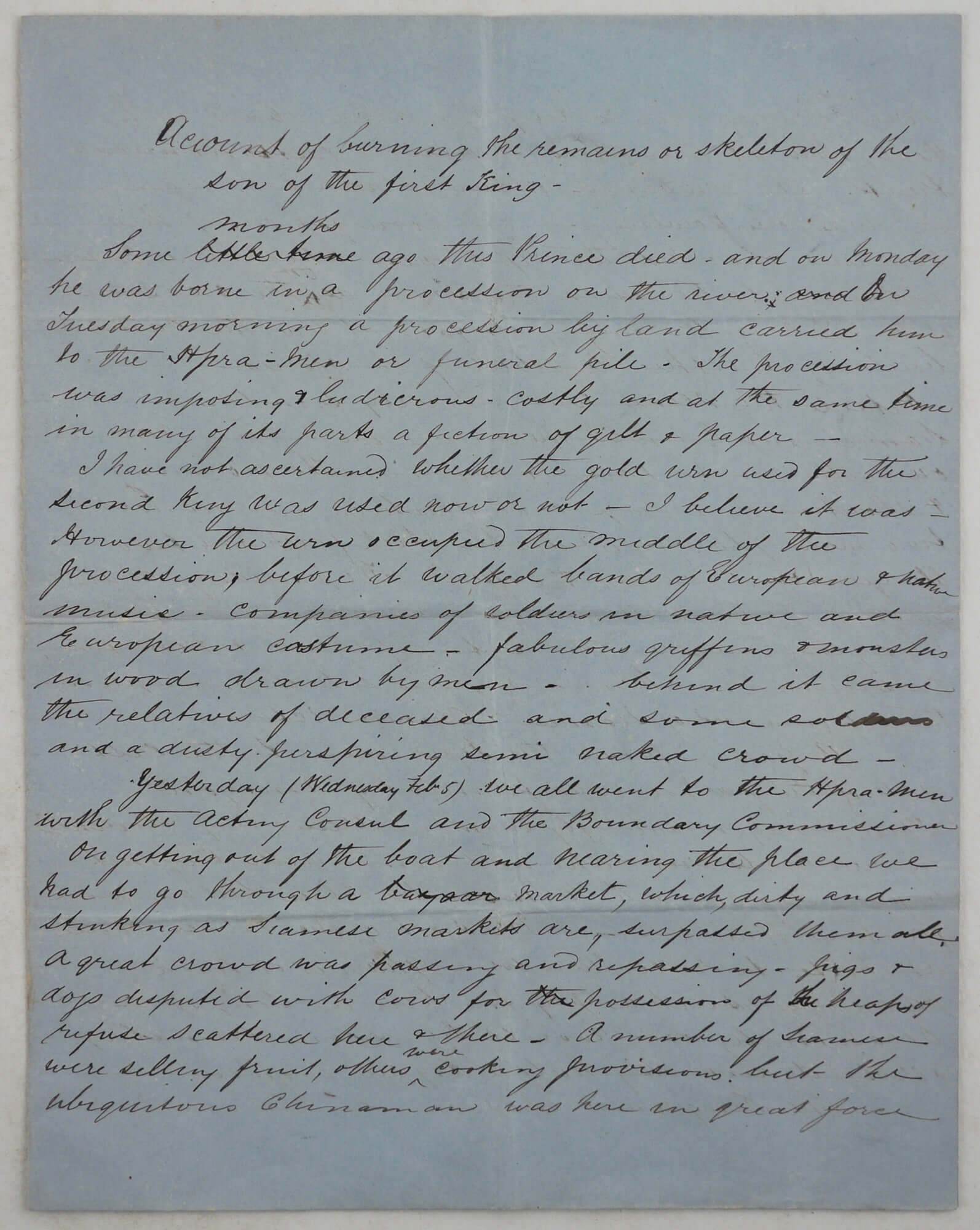

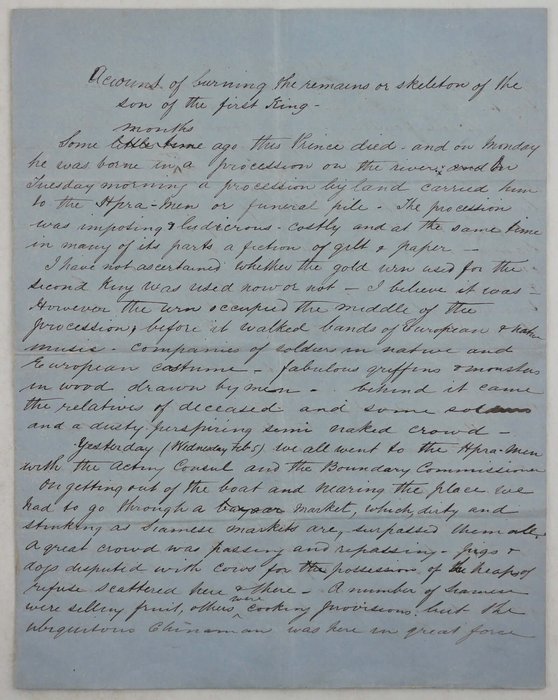

A passage in the letter and an additional extensive four-page manuscript describe the funeral or “hpra-men” [Phra Men] of a son of the first king of Siam which took place on February 3-5, 1868. Well-written, the account gives a vibrant picture of the funeral procession and ceremony, with interesting observations which reveal Edwardes’ role and attitude to the event. “… the gold urn <…> occupied the middle of the procession, before it walked <…> companies of soldiers in native and European costume, fabulous griffins & monsters in wood drawn by men, behind it came the relatives of deceased and some soldiers and a dusty perspiring semi naked crowd… [During the Phra Men ceremony] Siamese and Chinese theatricals were being carried on with much noise & vigour. The groaning & shouting of a large crowd which surrounded two men playing at double stick (each had two bludgeons) increased the effect. The proceedings at an English theatre will give you no idea of the barbarous & gorgeous dresses, the beating of gongs & tom toms, the shouting and blowing of pipes which accompany the performances of Siamese & Chinese actors.

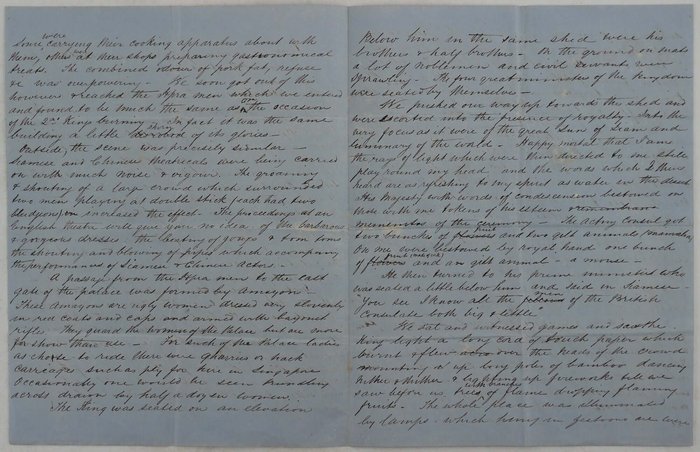

A passage from the Hpra-men to the east gate of the palace was formed by Amayons. These Amayons are ugly women dressed very slovenly in red coats and caps and armed with bayonet rifles. They guard the women of the Palace, but are more for show that use. <…> We pushed our way up towards the shed and were escorted into the presence of royalty. Into the very focus as it were of the great Sun of Siam and luminary of the world. Happy mortal that I am, the rays of light which were then directed to me still play round my head <…> His Majesty with words of condescension bestowed on those with me tokens of his esteem & mementos of the ceremony. The Acting Consul got two bunches of fruit and two gilt animals. On me were bestowed by royal hand one bunch of fruit (made of cork) and a gilt animal – a mouse. He then turned to his prime minister who was seated a little below him and said in Siamese: “You see I know all the men of the British Consulate, both big & little.” <…>

One or two gas lamps had also been put up. The whole scene at night was wonderfully interesting. Just in front of where we were sitting near the King was a large square lined by soldiers, and in this some fifty boys each with two coloured lamps were chanting and dancing. Then the dense crowd, their faces illuminated by the lurid glare of the fireworks, then the building in which the funeral pile had been erected with its illumination & gilt roof, and outside of the crowd rose five high wooden towers, festooned with lamps and illuminated at different points.

When I have opportunity, I will send home my gilt mouse and bunch of fruits. Each fruit contains a silver coin and the mouse is supposed to have five shillings worth of gold in it…”

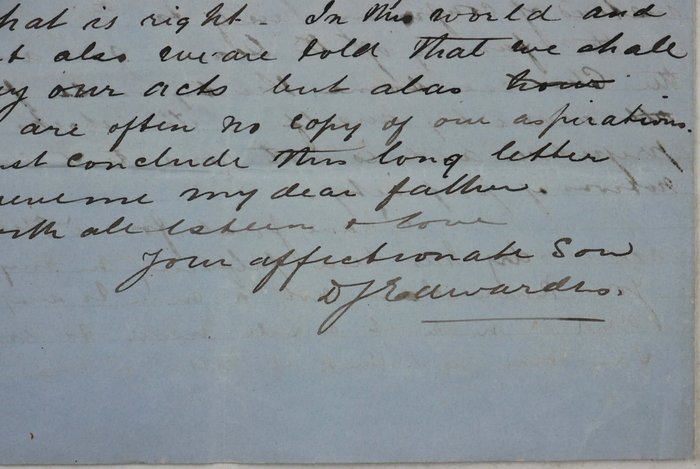

Very interesting are Edwardes’ notes about American Baptist missionaries in Bangkok. First, he wrote about “a new missionary and his wife here, Mr. & Mrs. Lisle” (Rev. William M. Lisle and his wife Anna Lisle, arrived to Bangkok in January 1868 in order to join the American Baptist Mission, but had to leave in June that year due to serious health implications): “I am going to call on them next week. He preached in church last Sunday, a rather better sermon than the missionaries here (with the exception of Dr. House [?]) are capable of. But he looks wonderfully young, has not a hair on his face and I should have taken him to be only 18, but I hear he is getting on for 28. If Siam is not to be converted it won’t be for want of missionaries”. Then Edwardes contemplated about the essence of missionary work and its development at the time: “In my younger days I used to think from the way they were talked about that missionaries were very superior beings or at least men far great on account of their self sacrifice and self denial. This was the idea I derived from platform speeches, but practically it is very different. I hear that they have misrepresented or need to misrepresent (it would be rather difficult now) the state of society in England and America. That certain vices were very uncommon and amongst other things that there were no whores in the country”.

Edwardes also left an interesting comment of the activity of a young female Baptist missionary Adele M. Fielde (1849-1916), who arrived to Siam in 1865, just to discover that her fiancé, young Baptist missionary Cyrus Chilcott had died a couple of months earlier. Miss Fielde stayed on and started to work in the mission, but “did not fit in with the Baptist missionary community. Her dancing, card-playing, and associations with the diplomatic community resulted in her dismissal from the mission” (Fielde, Adele, M. Baptist missionary to China known for her work with Bible women/ Boston University School of Theology, History of Missiology, see more). She had to return to the United States but was reinstated in the Baptist Mission in Swatow (China), where her 20-years work with the native women earned her a title of “the mother of our Bible women and also the mother of our Bible schools” (ibid.) Edwardes wrote in the letter: “Miss Field, a missionary lady instead of confining herself to Bangkok & living in the family of Dr. Dean [Rev. William Dean, 1807-1895, early Baptist missionary in Bangkok and Hong Kong] goes away to teach the Chinese some thirty miles from here all alone by herself. This shocks European prejudices and is not consistent with native notions of propriety.” In the end of the letter Edwardes mournfully contemplates about the decline of morale in the Old England which “is very rotten,” and that “in this present thirst for money what can we expect but that tradesmen… dishonest, officials corrupt & companies untrustworthy…”