#MA40

1848-1857

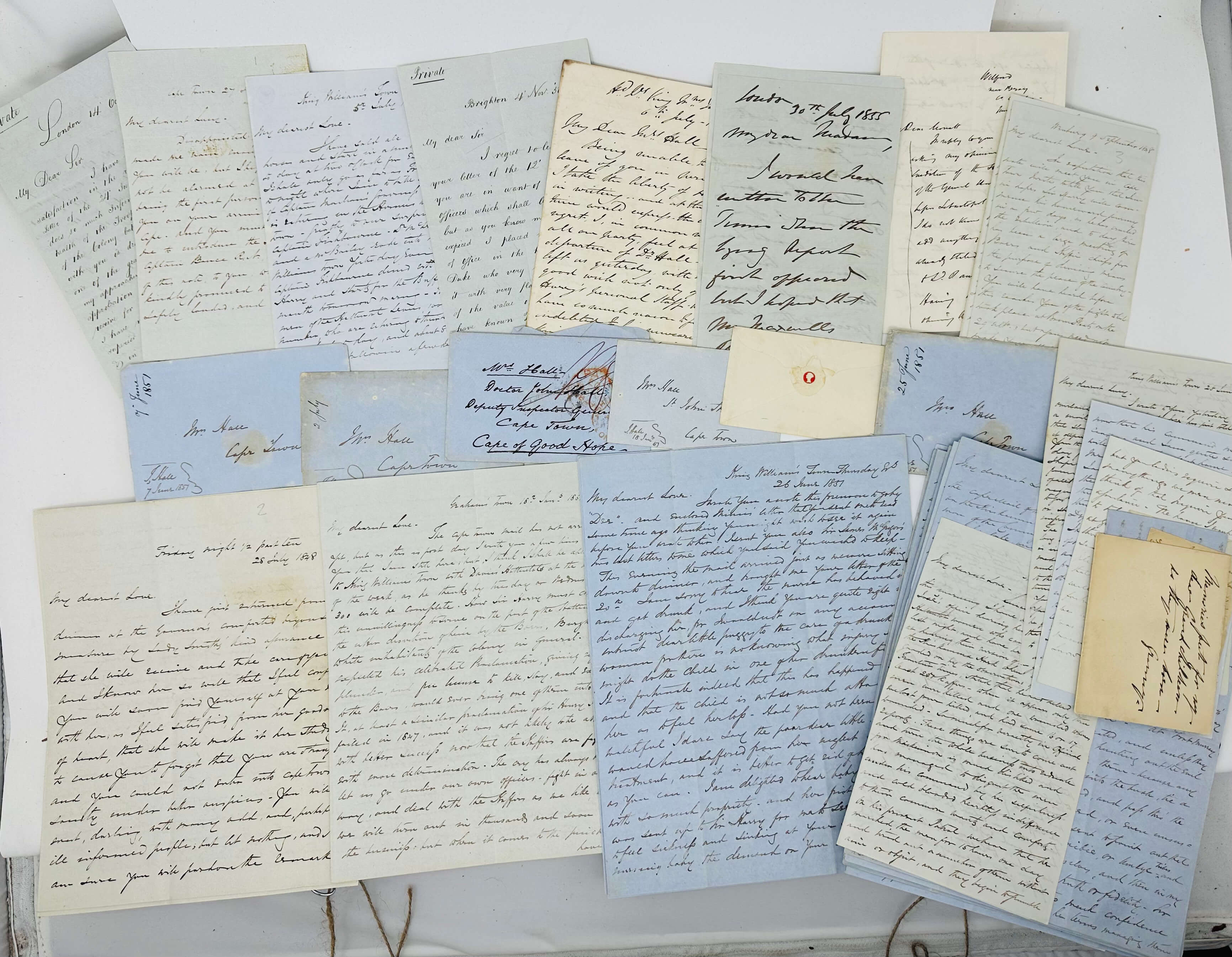

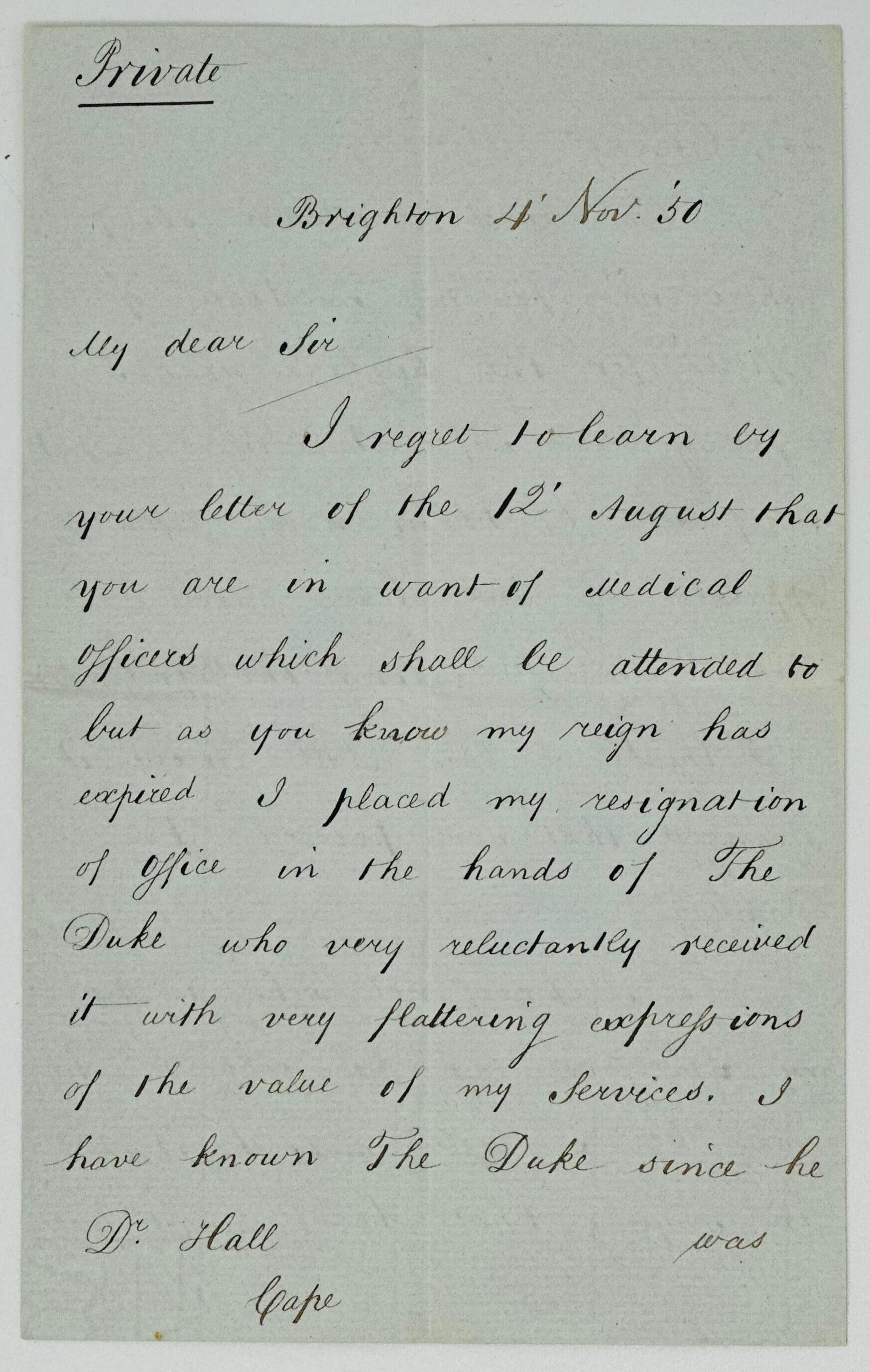

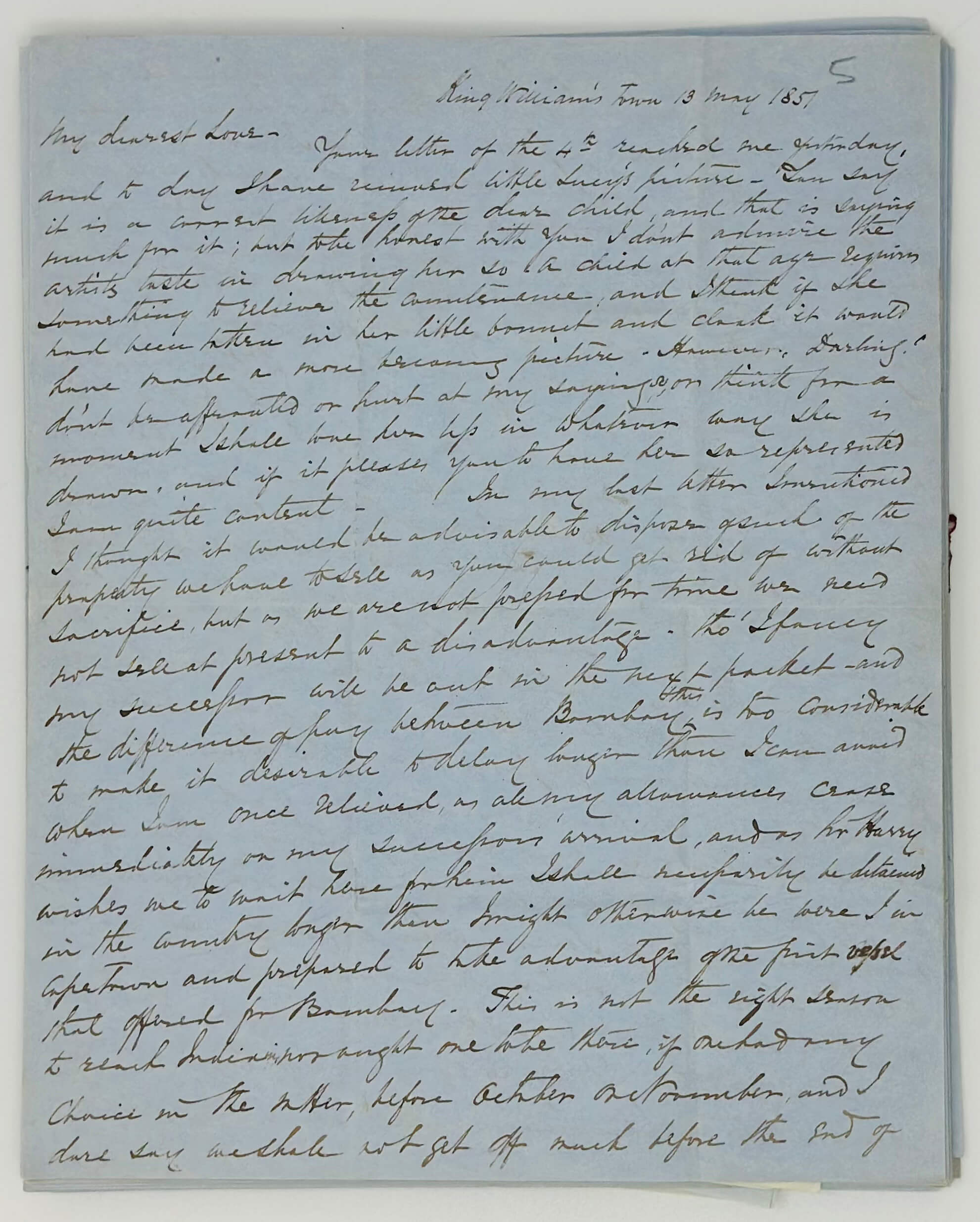

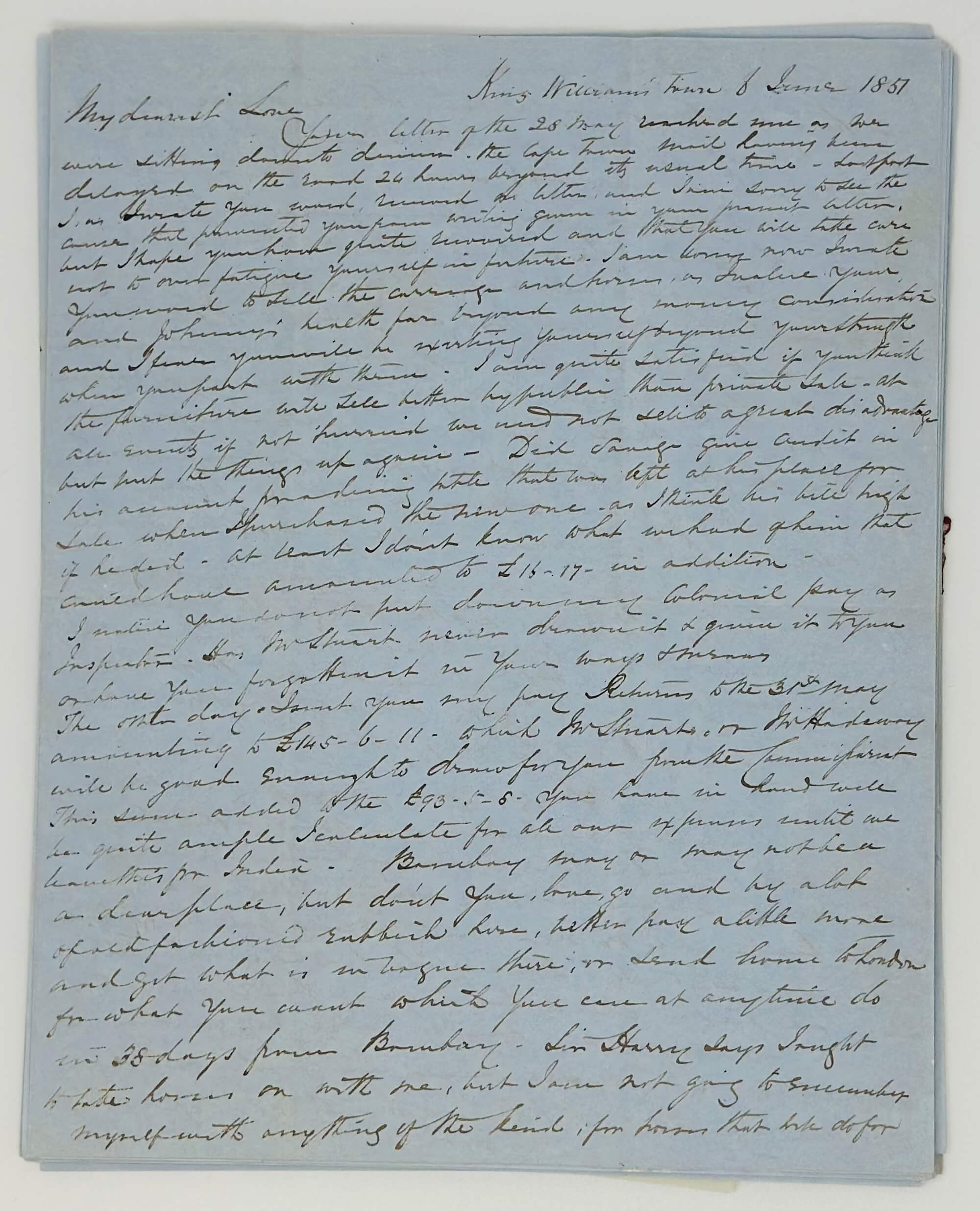

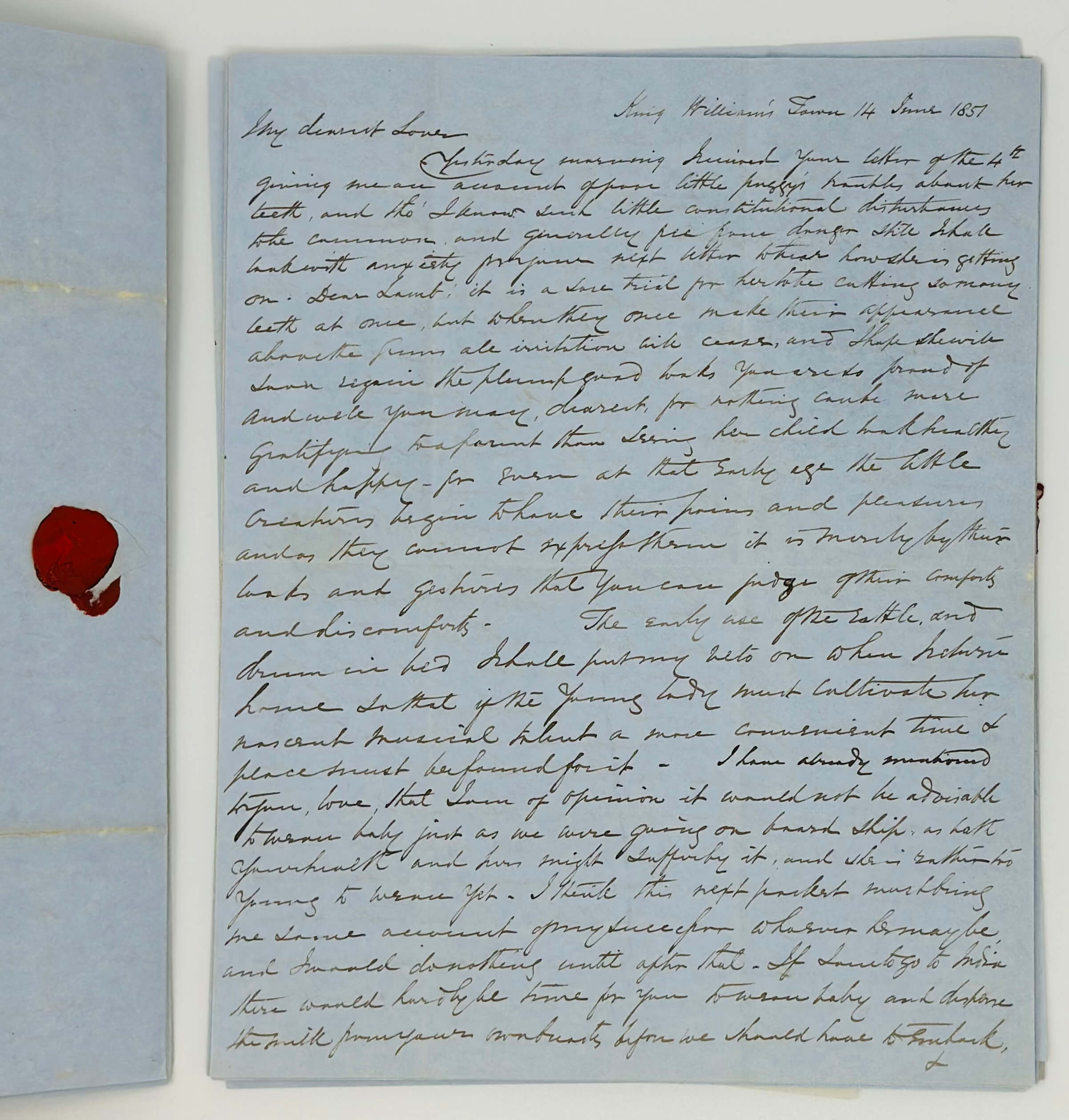

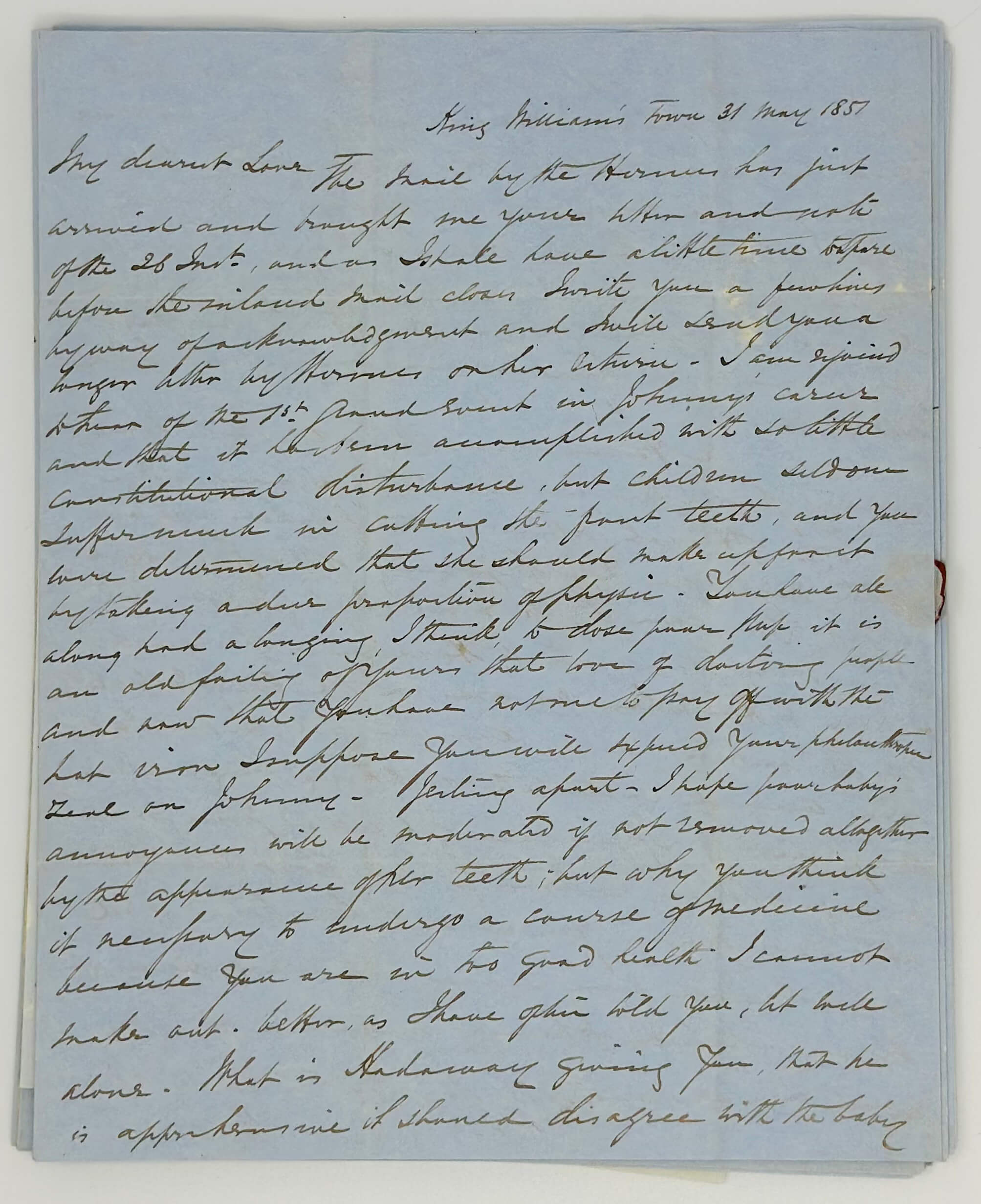

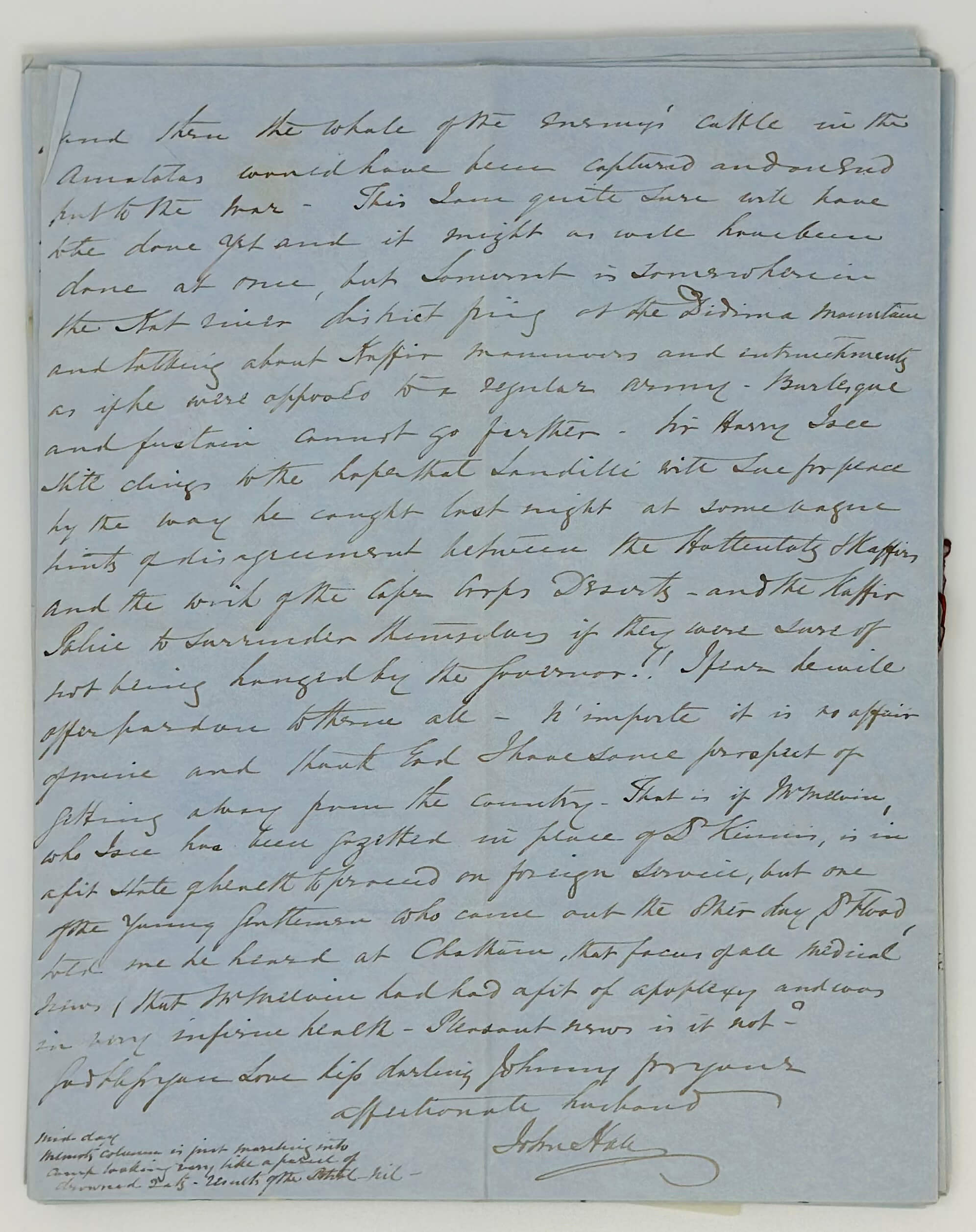

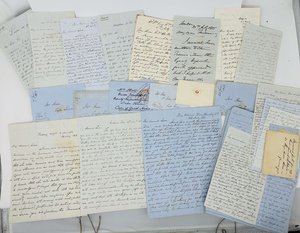

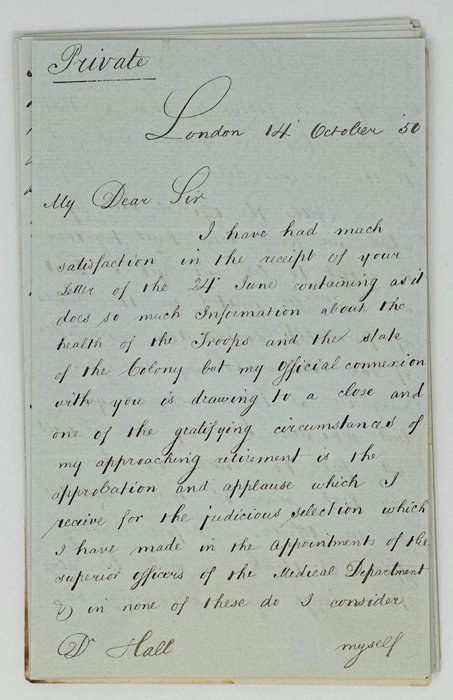

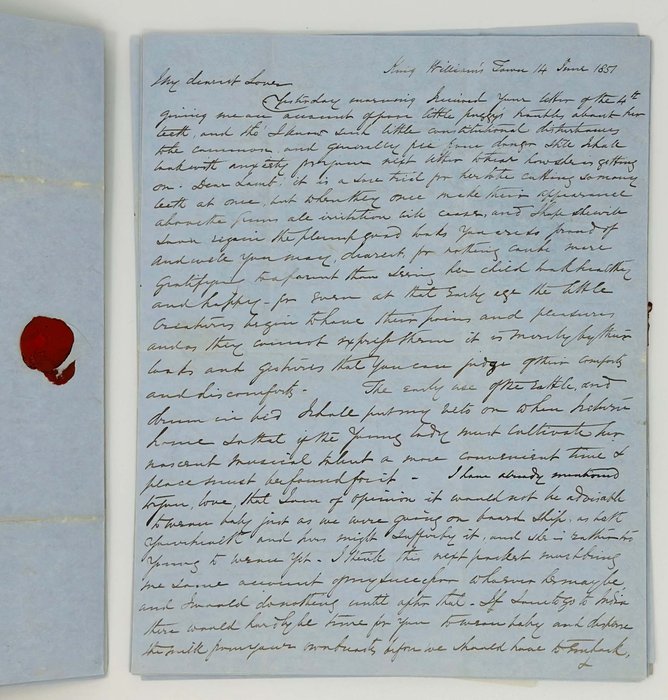

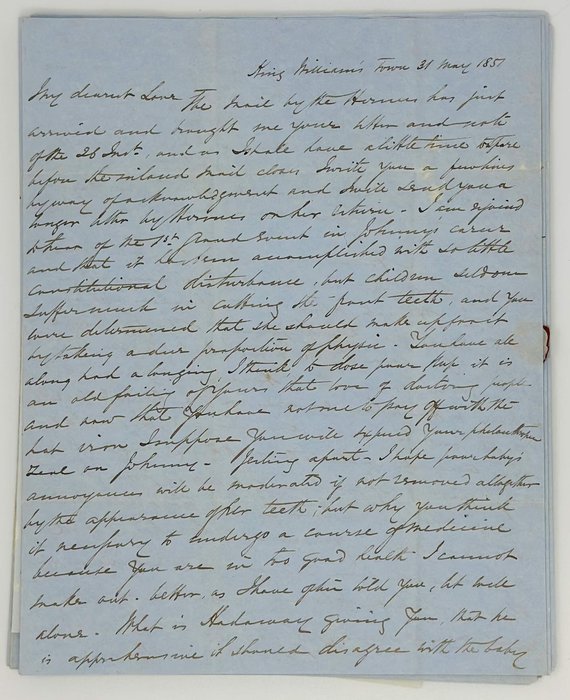

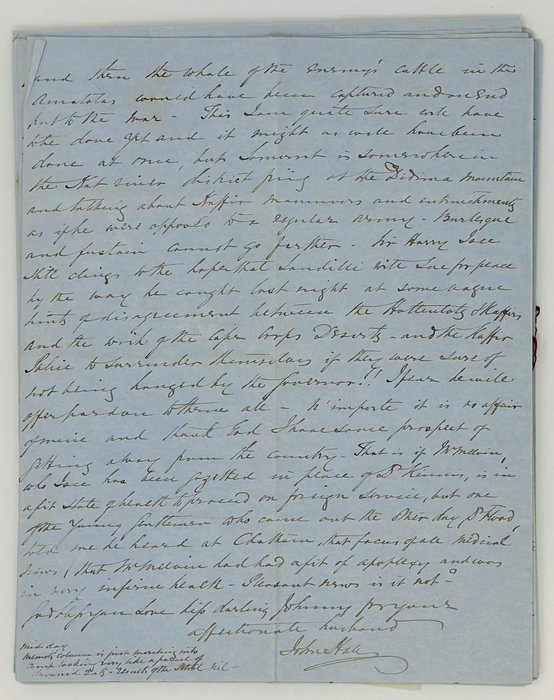

Twenty-two autograph letters signed, including six smaller ones, from ca. 20x12,5 cm (7 ¾ x 5 in) to ca. 18x11 cm (7 x 4 ¼ in), and sixteen larger ones, ca. 25x20 cm (9 ¾ x 8 in) or slightly smaller. The letters are from 3 to 8 pages long; in all there are ca. 110 pages of manuscript text. Brown ink on creamy and blueish laid and wove paper. With seven original envelopes from ca. 8x13 cm (3x5 cm) to ca. 6x10 cm (2 ¼ x 4 in); addressed and dated in period brown ink. One envelope with Lucy Hall’s ink note “Letters from by dear husband in June & in July, when he returned from the Kaffir War & was promoted to India.” With six more original ALS: two letters from Sir James MacGrigor to John Hall (dated 1850) and four letters to Lucy Hall written by different correspondents (dated 1849-1857), in all 27 pp. of text. Fold marks, a couple of occasional water stains, five Hall’s letters with minor holes after opening affecting one or two words, but overall a very good archive.

Historically significant archive of extensive content-rich letters, detailing on the service and life in South Africa of Sir John Hall, Deputy Inspector-General of Hospitals in the British Cape Colony in 1847-1851. He joined the Army Medical Service in 1815, serving in the West Indies (1818-27, 1841-44), Ireland (1835-36), Spain and Gibraltar (1836-39), South Africa (1847-51) and India (1851-54) throughout his career, but became most famous for his work as Inspector General of Hospitals in the British Army during the Crimean War and his conflict with Florence Nightingale. His full biography by S.M. Mitra, titled “The Life and Letters of Sir John Hall, M.C., K.C.B., F.R.C.S.” (London, 1911) is available online. A large collection of Hall’s diaries, correspondence, manuscript articles, etc. is now deposited in the Museum of Military Medicine (Keogh Barracks, Mytchett, Surrey), with digitized copies saved in the Welcome Library.

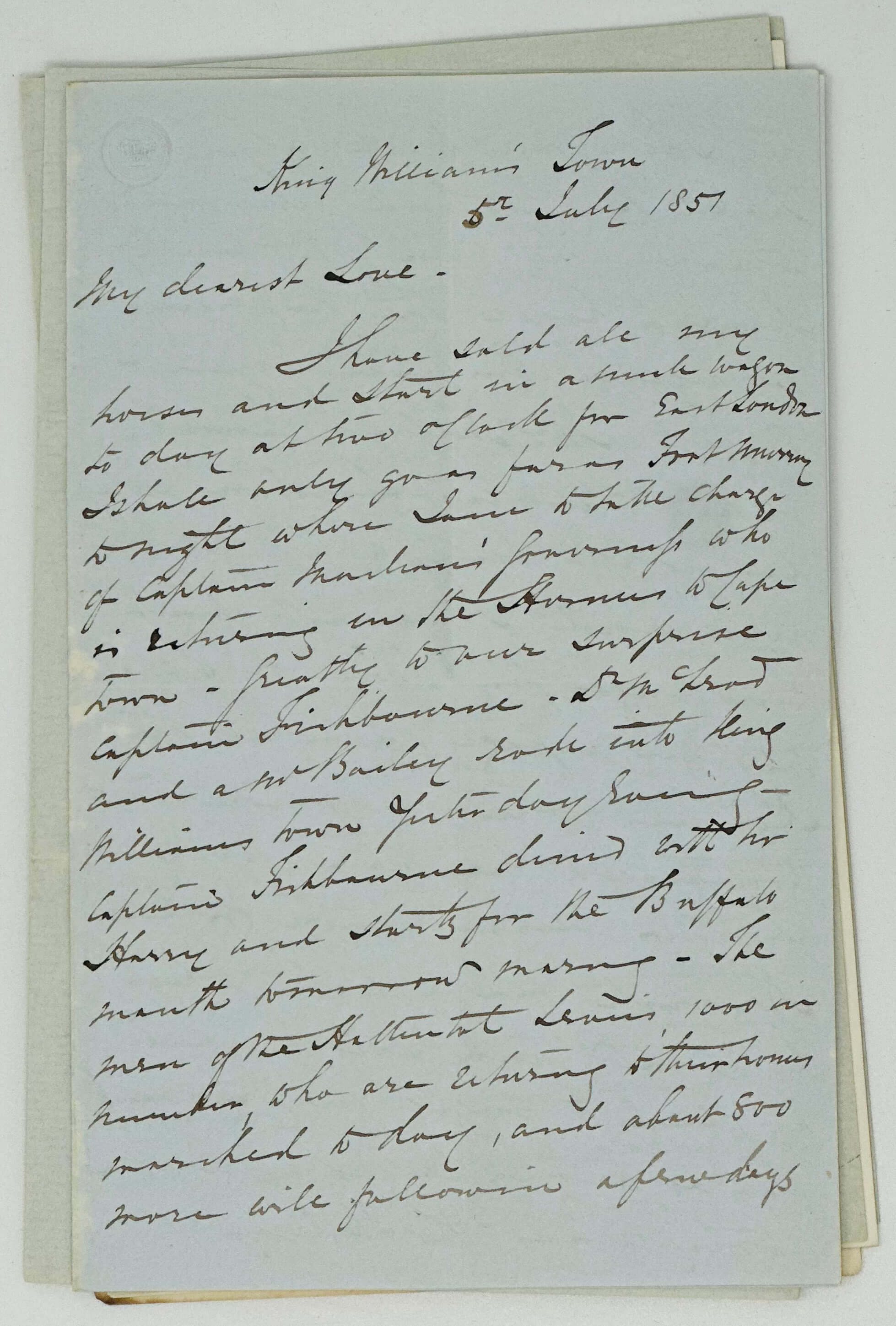

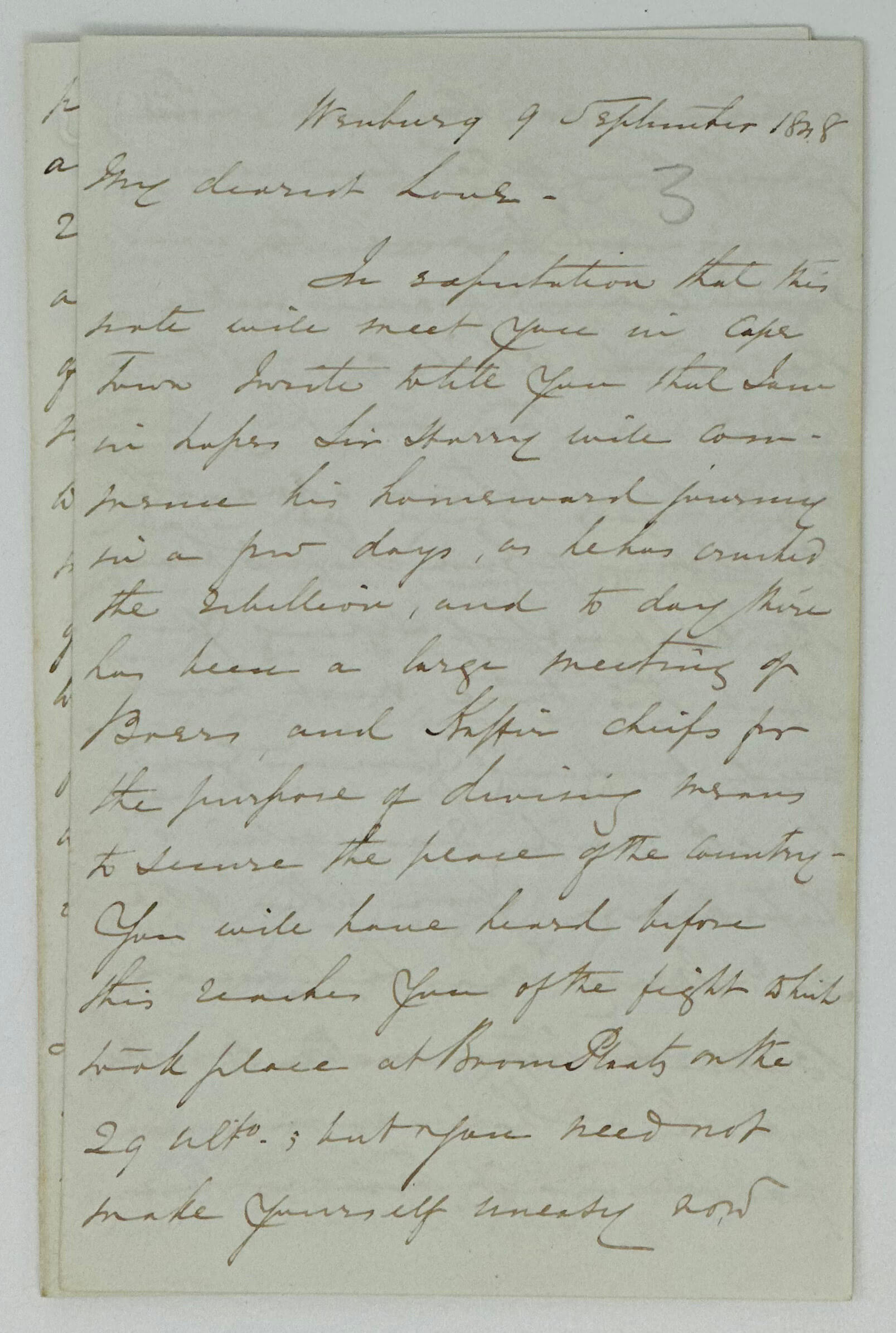

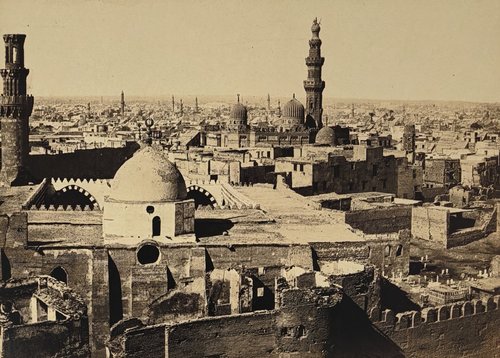

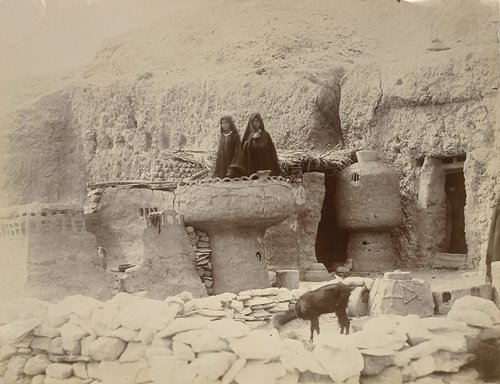

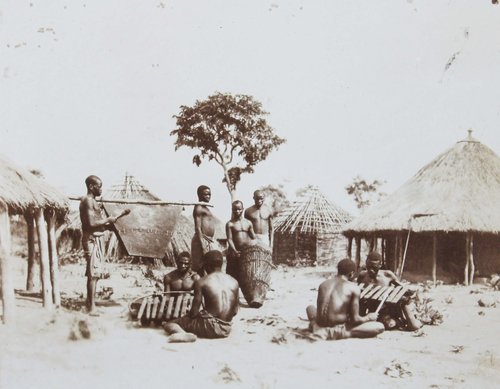

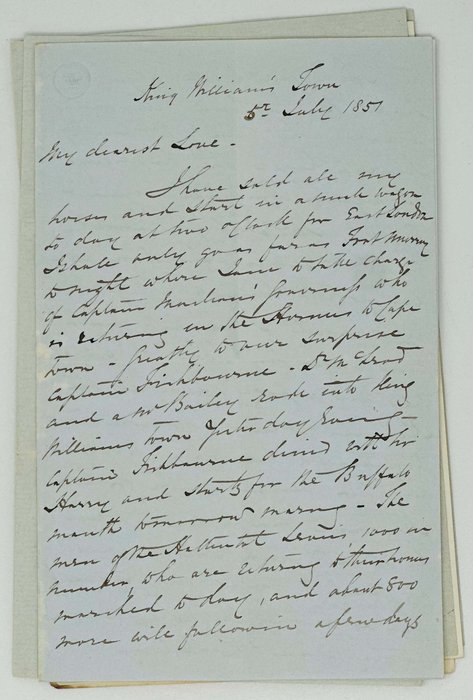

Our collection includes twenty-two long and detailed letters, written by Hall to his bride (and later wife) Lucy Campbell Sutherland (née Hackshaw, 1814-1907), who married him in Cape Town on October 31, 1848. The earliest three letters, dated July-September 1848, were written shortly before Lucy’s arrival to Cape Town and contain an interesting first-hand account of the struggle with the Boers led by Andries Pretorius (1798-1853) for the lands between the Orange and Vaal Rivers, and the Battle of Boomplaats in August 1848. Nineteen letters dated January-July 1851 are written from the front of the recently started “Kaffir War” (Eighth Xhosa War, December 1850 – February 1853) and report about the actions and decisions of Hall’s superior and friend Harry Smith (1787-1860, Governor of Cape Colony in 1847-1852), the movement of the troops, casualties, the need for medical supplies, mention several British military commanders, Xhosa chief Sandile, “Hottentot” (Khoenkhoen) warriors, and others.

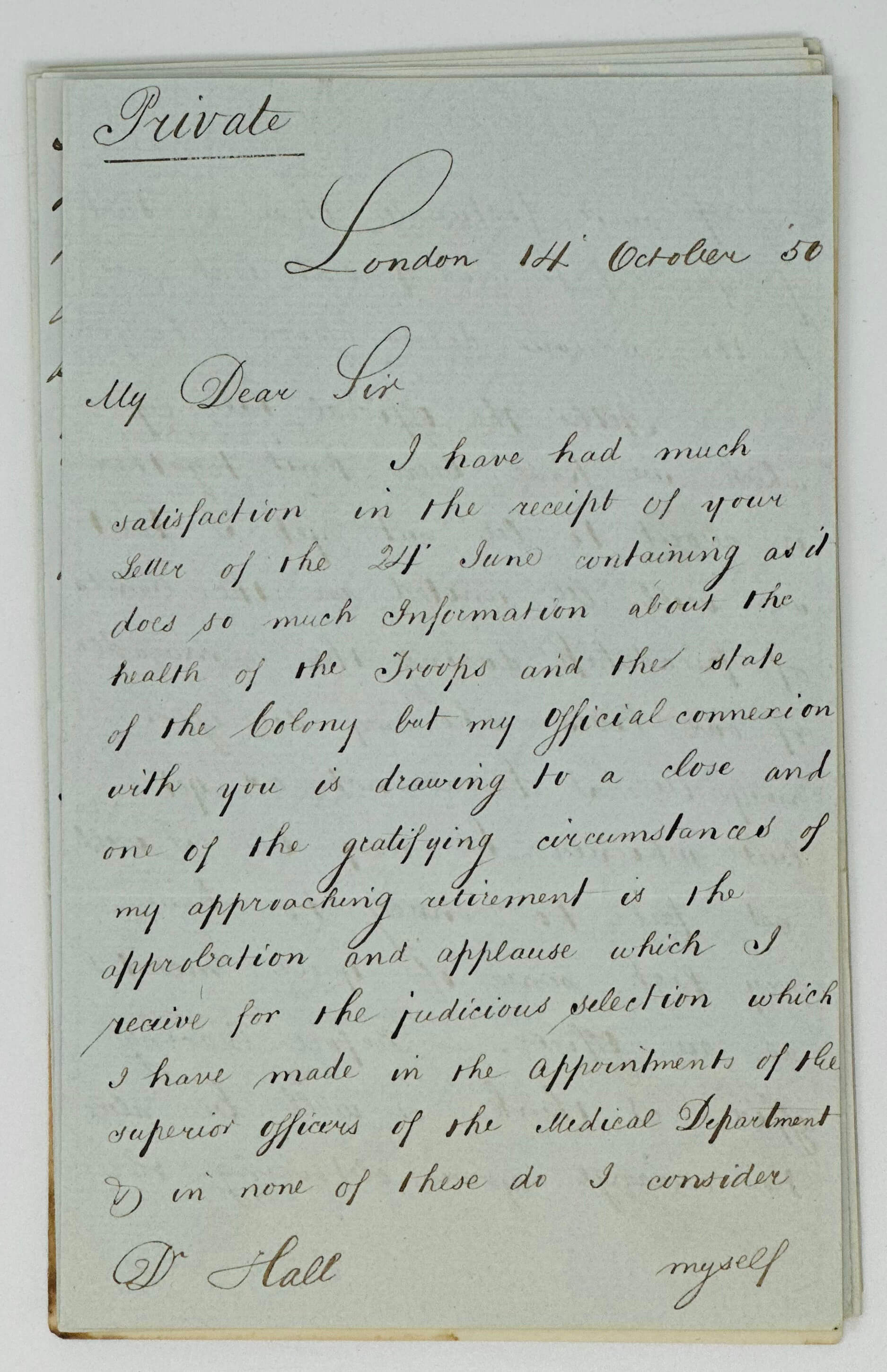

The collection also contains two letters to John Hall from Sir James McGrigor (1771-1858), a noted physician and military surgeon, then Director-General of the Army Medical Service (1815-1851). Written in secretarial hand and signed by McGrigor, the letters mention Hall’s possible appointment for “the Presidency in Bombay,” McGrigor’s “approaching retirement,” and send regards to Sir Harry Smith.

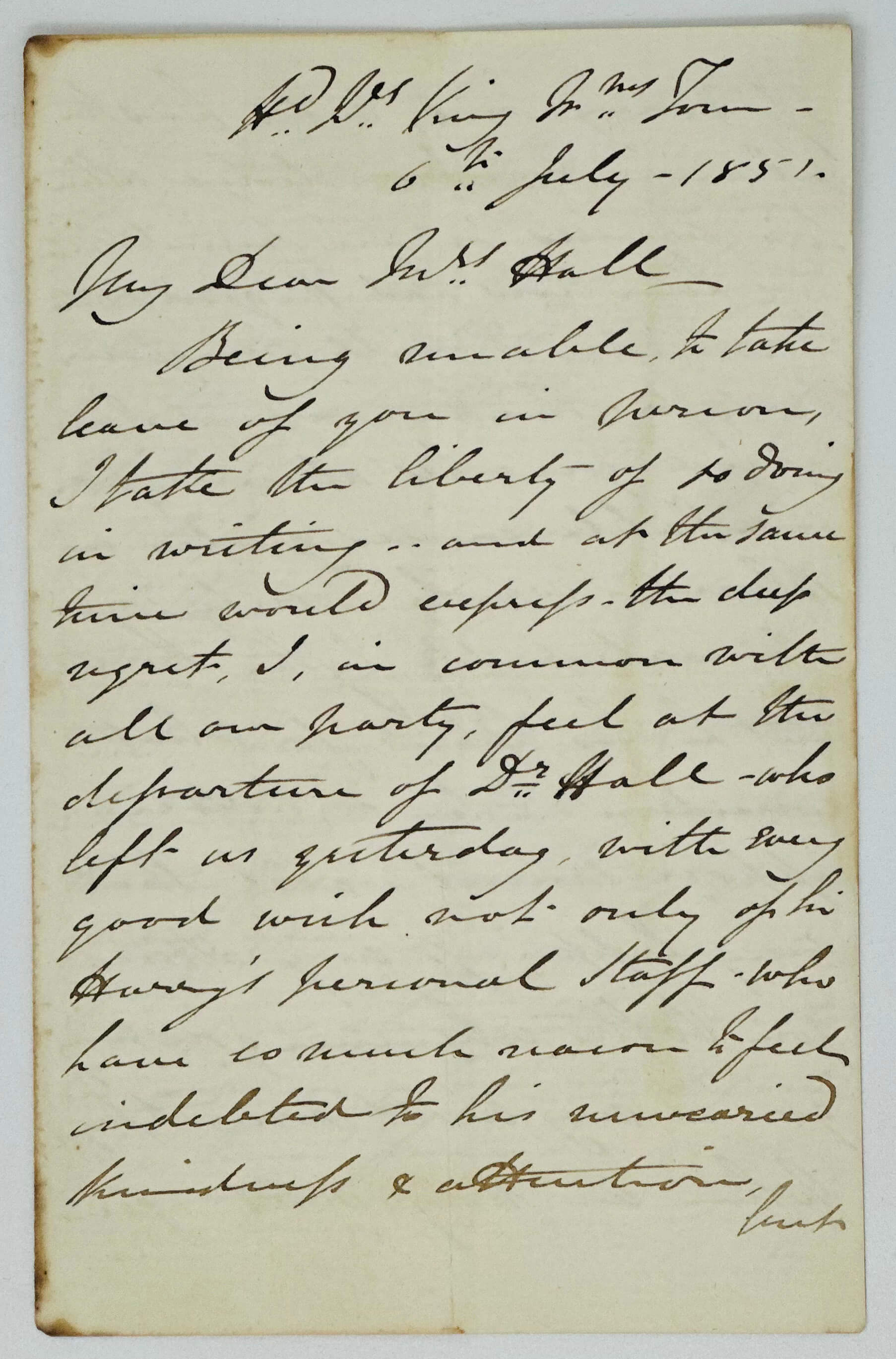

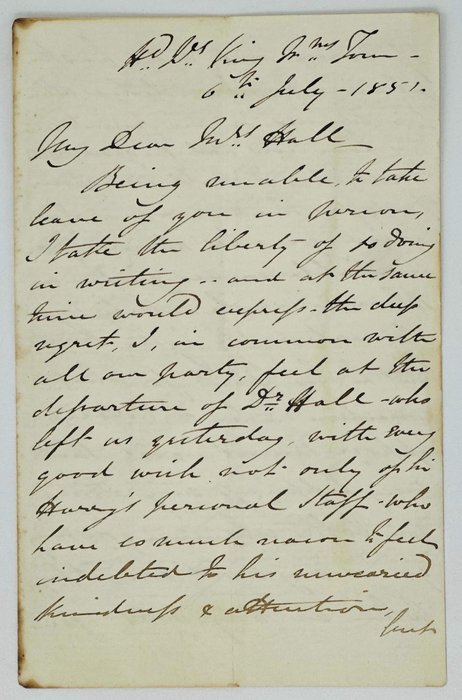

Four letters to Mrs. Hall include an ALS by Sir Edward Allan Holdich (1822-1909), the ADC of Sir Harry Smith and a participant of the Eighth Xhosa War (dated “King William’s Town, 6 July 1851”): “I <…> express the deep regret I, in common with all our party, feel at the departure of Dr. Hall, who left us yesterday, with every good wish not only of Sir Harry’s personal staff who have so much reason to feel indebted to his […?] kindness & affection, but of every one who has the pleasure to acknowledge either his services or his friendship. <…> When we may meet again is very uncertain. At the expiration of service in this Colony, I am also bound to India, but my lot will I trust be cast far in the northeast, that I am not likely to be near Bombay, unless on my road home, whither I trust you will long have preceded me. <…> Just as I close my note, that horrid old Doctor Melvin walks in. He may be a very good old man &c., but he never can at all compensate for or half satisfactory replace the loss of our late Doctor.”

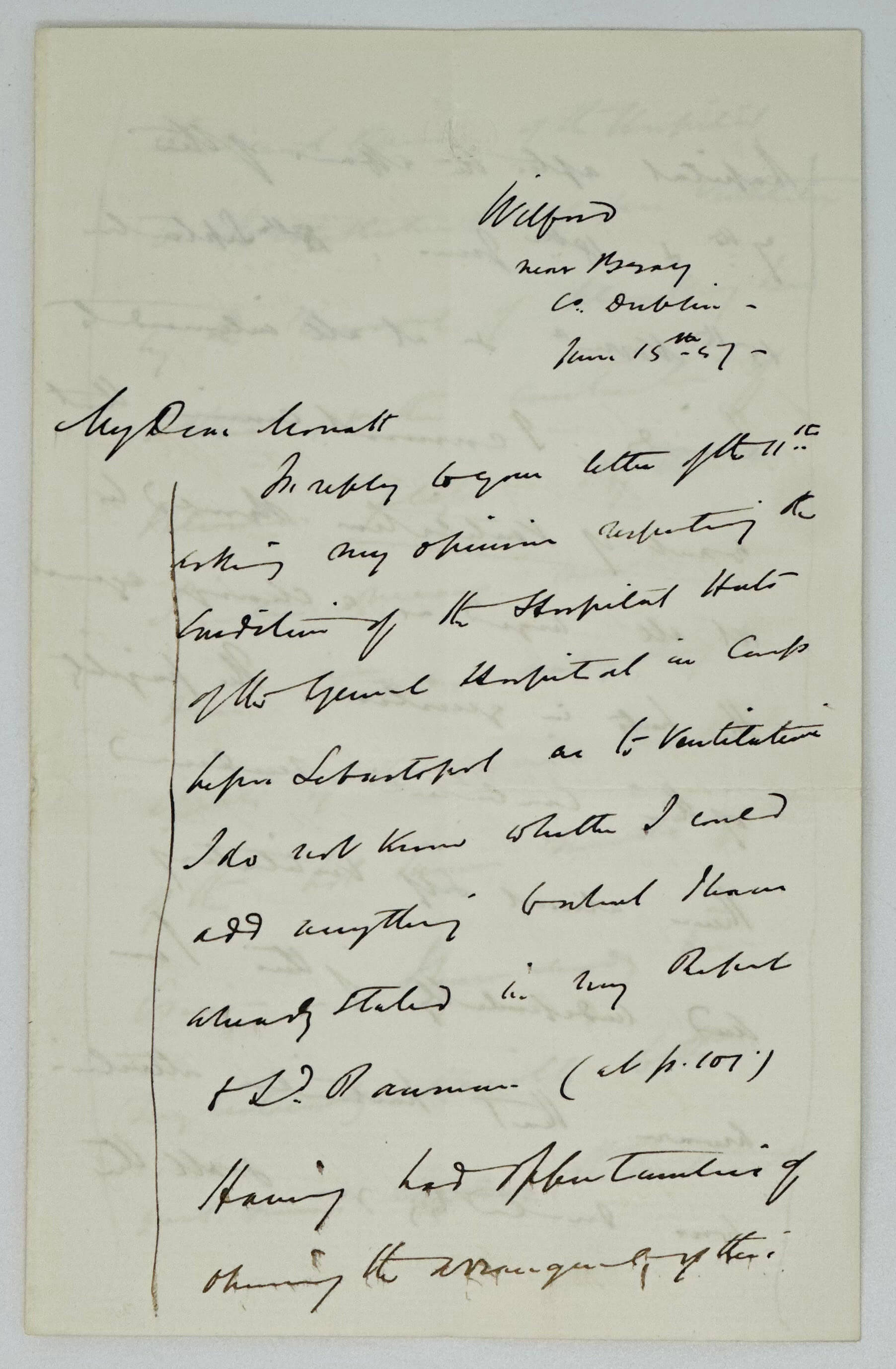

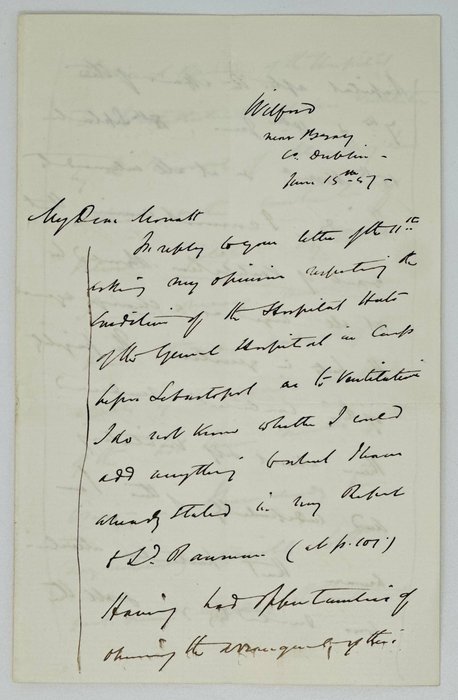

There is also an ALS to Mrs. Hall from Henry Blenkinsop (1813-1866), Senior Surgeon of Warwick Dispensary and Medical Officer of the Union Workhouse (dated “Warwick, 29 April 1849,” with the original envelope). A letter by David Dumbreck (1805-1876), dated “London, 30 July 1855” and a letter dated “[June?] 15, 1857” relate to the public investigation into John Hall’s service as military Inspector-General of Hospitals during the Crimean War and his alleged failure to provide proper medical care of wounded British soldiers in Turkey and Crimea. The collection also includes an envelope with small memorabilia and reproductions of paintings, annotated by Mrs. Hall in ink “Memories put for my dear Grandchildren as they were born. Granny.” Overall an important extensive collection of original letters by a prominent British colonial administrator in Cape Colony, with an eye-witness account of the struggle between British and Boers in what would soon become the Orange River Sovereignty (1848-1854) and the Eighth Xhosa War (December 1850 – February 1853).

Excerpts from John Hall’s letters:

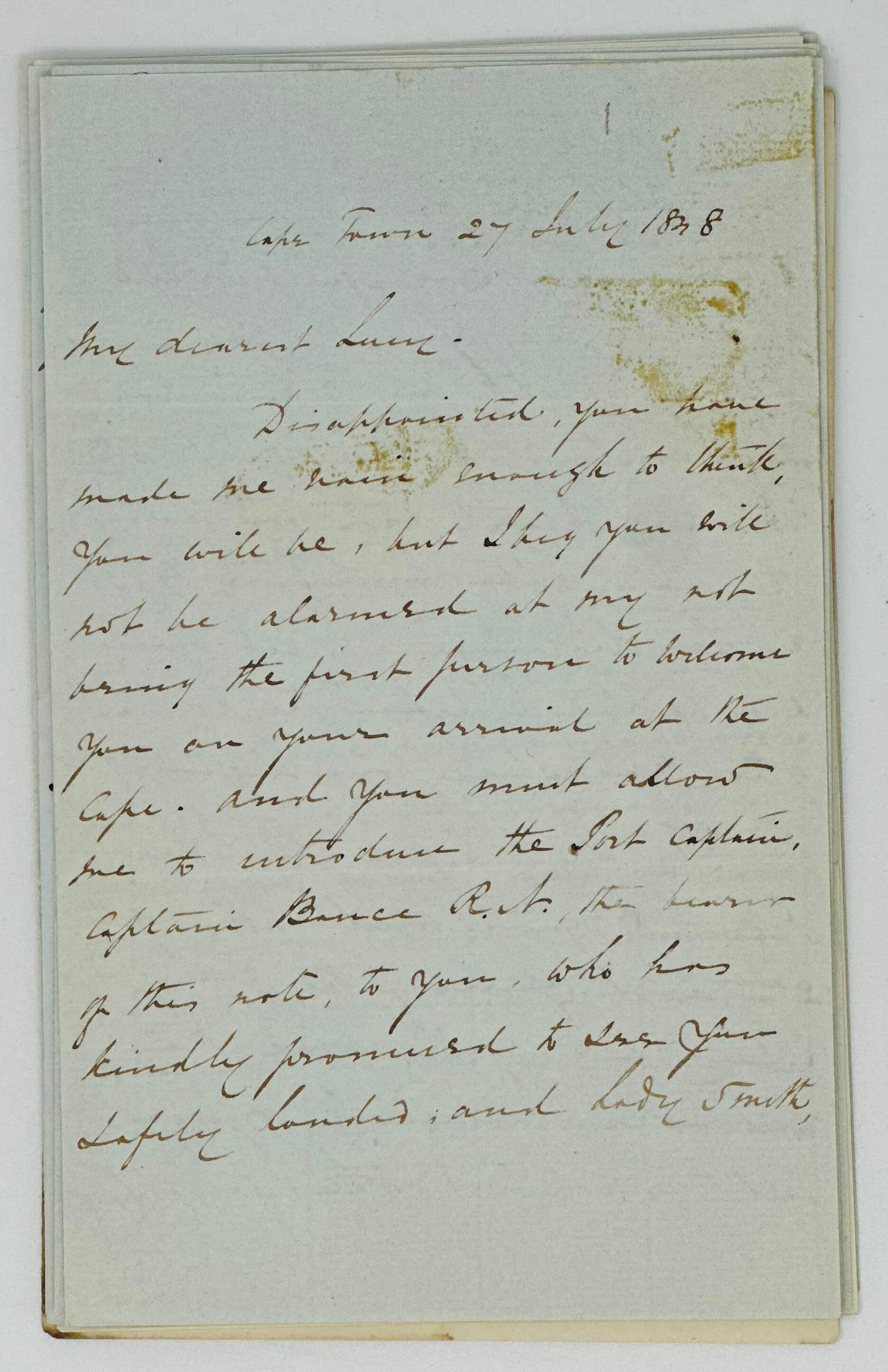

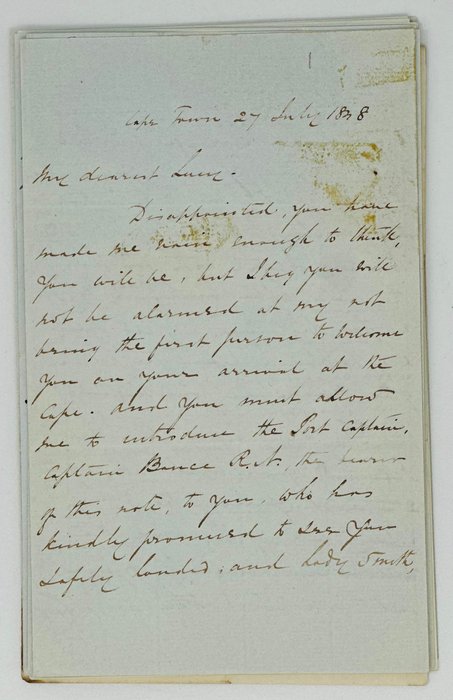

Cape Town, 27 July 1848: “<…> I beg you will not be alarmed at my not being the first person to welcome you on your arrival at the Cape, and you must allow me to introduce the Port Captain Bruce R.N., the bearer of this note, to you, who has kindly promised to see you safely loaded, and Lady Smith, God bless her for it, has offered to send her carriage for you and receive you at Government House until my return from the Frontier, to which part of the Colony I start with Sir Harry the day after tomorrow, and as the distance is great I may not be back before the arrival of the Maidstone from England. <…> I know you will love when you get acquainted with her [Lady Smith], she is so kind and amiable it cannot be otherwise, and she is so affable that you will hardly feel she is an entire stranger to you <…>.”

[Cape Town], 28 July 1848: “<…> You will meet, darling, with many odd and, perhaps, ill informed people, but let nothing, and I am sure you will pardon the remark, tempt you to make any source of ill natured observations on any one, as they are all connected with one another, and what you say might be repeated and continued in a way that you did not intend. <…> I do not like the house I am in and I have deferred furnishing it from day to day in hopes that I might per chance have the benefit of your good taste in doing it, and now if you like at anytime to look into the upholsteries or furniture […] houses and make a selection you will greatly oblige me <…>.”

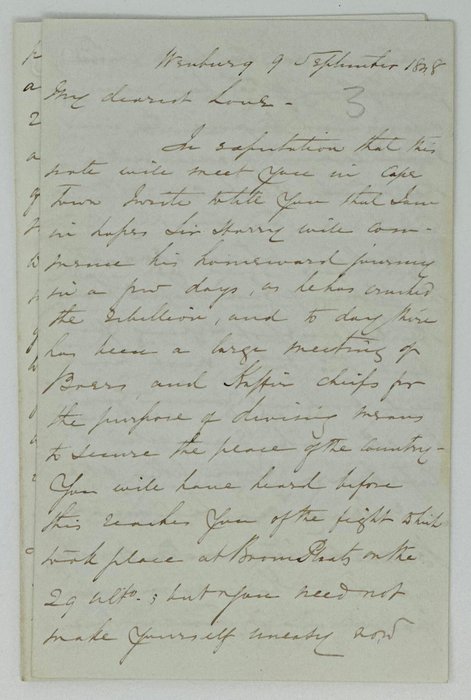

Wenburg [Winburg, Orange Free State], 9 September 1848: “<…> I write to tell you that I am in hopes Sir Harry will commence his homeward journey in a few days, as he has crushed the rebellion, and today there has been a large meeting of Boers and Kaffir chiefs for the purpose of devising means to secure the peace of the country. You will have heard before this reaches you of the fight which took place at Boom Platz on the 29th ultmo.; but you need not make yourself uneasy now as there is not the least chance of anything of the kind occurring again <…>. When we leave Bloemfontein the Governor will [board with his wagon?] and he has just told me that we are to have this on Tuesday the 12th. He will most likely to be detained two or three days at Bloemfontein and then he goes to visit the military stations on the Eastern frontier to see how his Kaffir policy is working. Sir Harry is a man of great energy, activity and ability and it is a pleasure to serve under him as he has an opinion of his own and is able to judge for himself. His escape the other day was almost miraculous as he was left alone at one time and all the Boers knew him by the dress he wore as it was the same he had worn when he was amongst them in Jany. Last, and many of them, we have now ascertained, aimed at him. But there is a providence over all and the wicked design of these evil-mended men was fortunately frustrated.”

Graham’s Town, 18 January 1851: “<…> How Sir Henry must chafe at the unwillingness to serve on the part of the Hottentots, and the utter desertion of him by the Boers, Burghers, and white inhabitants of the Colony in general. I never expected his celebrated Proclamation, giving right of plunder, and free licence to kill, slay and exterminate to the Boers, would ever bring one of them into the field. It, at least a similar proclamation of Sir Henry Pottinger’s failed in 1847, and it was not likely to be attended with better success now that the Kaffirs are fighting with more determination. <…> Had they [Boers] turned out atrocities, I have no doubt, would have been committed by them far surpassing those of the Kaffirs themselves, for I have heard men talk about shooting men, women and children as if they were dogs. The Kaffir mode of warfare does not humanize men, but it is their mode of waging war, and we know it; but that is no season why we as Christians and civilized people should imitate them in all that is most objectionable in their system…”

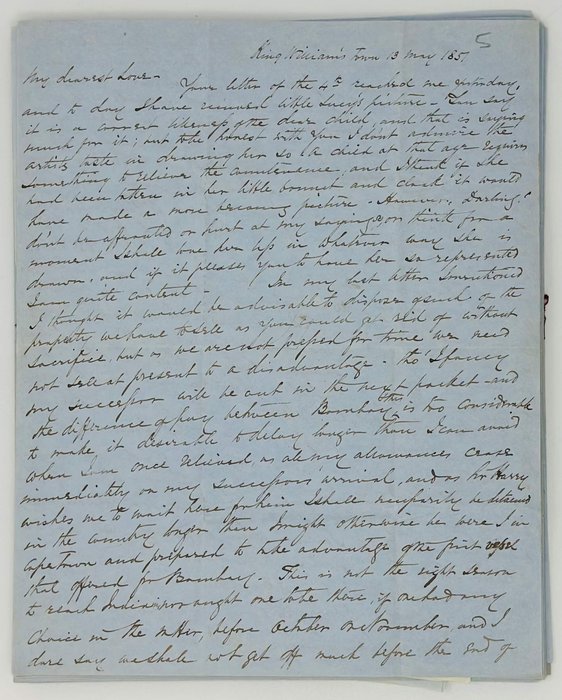

King William’s Town, 13 May 1851: “Major Wilmot’s Patrol came in the evening. He has captured about 40 head of cattle and done little or no damage to the Kaffirs during his five days wandering in the hills. This morning a body of Kaffirs attacked him on his way back but did him no damage as none of his people were either killed or wounded. We could hear the firing distinctly here. <…> Montague’s mounted force from the West (10 in number) which arrived yesterday is a miserable failure which not likely to be of any use beyond consuming rations and forage, which are difficult to procure here…”

King William’s Town, 14 May 1851: “… I send you another abstract from the Zuid [De Zuid Afrikaan] what I think will amuse you not that there is any truth in the vaunted deed of courage performed by Sir Andries and his brave Burghers during the last truce, whose prowess no one but the Editor of the newspaper ever heard of, and even he must have dreamt it. Captain Fisher, the Barrack Master at Fort Beaufort, who commands a body of […?] at Eland Fort in the Kut River, has had a great fight on the 1st with the Kaffirs and Hottentots in that neighbourhood in which he had one man killed and eight wounded, and that according to custom, he slew at least fifty of the enemy, but notwithstanding they continued most pertinaciously to pursue him all the way home!!”

King William’s Town, 19 May 1851: “The Kaffirs are a remarkably shrewd race, and estimate Sit Harry’s acts at their true value.

The other day I was much amused at an observation made by that cunning old fellow [Cobus?] Congo, the Demosthenes of the Kaffirs, who replied with great naivete to one of Sir Harry’s fine speeches. “The Karris say, this is their usual way of stating a case, when peace comes again that we who sat still at home will be put aside, and Sandilli & those who have joined in the war be taken into favour and made much of.” Now this was such a home hit that both Cloete and I could not help laughing at it. The Kaffirs laugh too when they get presents, and as pleasant news is always well rewarded, they are cunning enough to prime all their reports to gratify our vanity, and in that way we obtain most exaggerated accounts on all subjects…”

King William’s Town, 19 May 1851: “Distant firing has been heard this evening in the Amatolas by the Fingoes, which I should say argued against the success of our patrols operating there. The force engaged is too strong to apprehend any serious revival but I think it probable the Kaffirs are following them and attacking the rear guard whenever favourable opportunities present themselves, and knowing the paths of the country as well as they do the advantages are in their favour. Genl. [Somerset?] in place of operating from the opposite direction on Sandilli’s strong hold has gone away to the Kat River district, and the last we heard of him he was firing shells from his guns at the side of a mountain, and writing absurd burlesque despatches of his proceedings…”

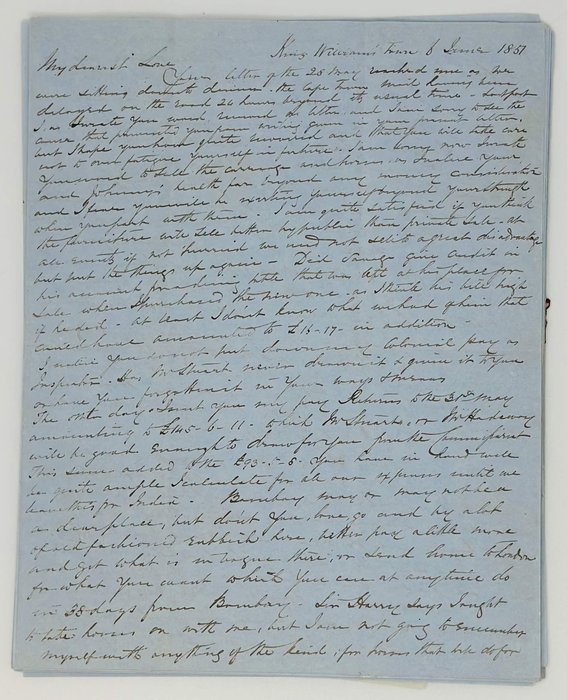

King William’s Town, 8 June 1851: “A Hottentot boy, son of a Sergeant Jacobs in the Cape Corps, who ran off with the Hottentot deserters from the Cape Corps, returned to his father today. He says Sandilli sands the Hottentots into the Colony to steal cattle and that a party of them is there at present, the very people I suppose who have been inciting the Hottentots at the Theopolis missionary station to commit the depredation they have done & then leave the Colony. He says the Kaffirs have made them all exchange their double barrelled carbines for single barrelled guns, and that they are getting short of ammunitions. The number of killed mentioned by this lad during our great patrols into the Amatolas by no means comes up to our own […] estimate, but the contrast is too ludicrous to mention. The boy’s amount is consistent enough…”